City of a Chameleon Colors

Written by Ruth Taylor, Executive Director of the Newport Historical Society, and C. Morgan Grefe, Executive Director of the Rhode Island Historical Society.

This article first appeared in Newport Life Magazine. Click here to read the version as it appeared in print.

Women Working in the Explosives Department at the U.S. Naval Torpedo Station, Goat Island c.1940, image from the NHS Photo Collections

For almost four centuries,Newport has been a center of creative entrepreneurship and innovation. We have invented and reinvented our city to take advantage of our own natural assets and the circumstances in the world around us. We have experienced boom, and bust, and have come out of each downturn ready to make our way in a changing world. Now as this growing city celebrates its 375th anniversary, we look back at how its adaptations to these shifting cultures have created a city of international esteem.

In 1639 a group of adventurers arrived at the southern end of Aquidneck Island and made a settlement here. The act of self-invention that is required to leave one’s whole world behind and come to a new and unfamiliar place should not be minimized. But these settlers, unlike the Puritans who settled what is now Massachusetts and Connecticut, also seem to have carried a genuine openness to change and difference with them. Instead of establishing a new society with the same practices and approach to life that they left behind, they sought to redefine the bonds that hold society together — not narrowly religious, but rather through a new sense of the civic space. Certainly Roger Williams deserves a great deal of credit for this, but nowhere can it be seen to flower more than in Newport.

Freed from concerns about religious differences, Newporters focused on making a living. First, they established farms, and in fact the first seal of the city depicts a sheep.

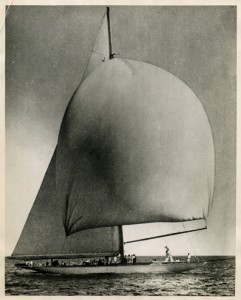

Ranger, William K. Vanderbilt’s J-Class yacht and defender of the 1937 America’s Cup. Image from the NHS photo collections.

But the rocky land and limited island acreage made farming less than ideal. So these earliest Newporters re-imagined: they began to focus on the advantages at hand. These included a deep-water harbor and the international networks for trade that otherwise persecuted minorities, such as the Quakers and the Jews, brought with them as they came seeking religious freedom. By the early 18th century, Newport was a growing maritime center, which would come to rival New York and Boston in trade and wealth. Newport was importing porcelain from China, cloth from Russia and India, mahogany from the islands and South America, and creating a wide variety of fine goods for trade. Newporters also engaged in the “triangular” slave trade, creating more than a dozen distilleries to make rum for exchange.

As its wealth grew, Newport deliberately set out to establish itself as a thriving British city, recognizable as such by any visitor. The earlier organic development of the city — lacking a religious center, it grew around the vocations and work-places of its residents — was replaced by community-minded urban planning. A spacious civic center was created at the Parade, now Washington Square, and a series of public buildings were built, including the Colony House and the Brick Market, which still stand today.

But the same maritime activity that brought wealth to Newport made it a flashpoint for troubles with the British Empire. Trade restrictions were felt here as deeply as anywhere, and the build-up to and conduct of the American Revolution damaged Newport’s trade economy. However, this conflict also provided an opportunity for new paths to economic activity through the Navy. Rhode Island’s merchant ships became part of the first colonial Navy, and Newport merchant wealth financed the creation of the Continental Navy. Newport’s Katy, owned by Providence’s John Brown, became the Continental Sloop Providence, captained by the famous John Paul Jones.

The British occupation of Newport during the American Revolution destroyed infrastructure and trade connections. Newport’s economy was in ruins and individual merchants fled to Massachusetts, Providence and further afield. The enterprising spirit of the population was not dead, however. The undeniable allures of Newport, including a salubrious climate, spectacular vistas and proximity to growing urban centers of the new nation, helped the city redefine itself after the Revolution took its toll. While the Industrial Revolution urbanized the landscape and created wealth elsewhere in the state, it mainly passed Newport by. This preserved the undeveloped, natural character of the city and its environs. The sea breezes not only kept the visitors cool, they helped to create a more healthful environment away from the congestion of urban centers developing elsewhere. As cities such as Philadelphia and New York were industrialized, they were plagued with outbreaks of then-mysterious illnesses like Yellow Fever, while Newport was largely spared. As a growing number of families in the 19th century had the ability, and the desire, to spend their summers out of the hot city centers, Newport became a favorite destination.

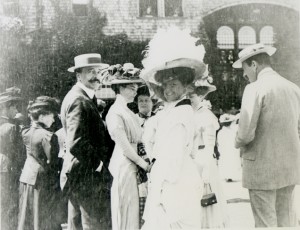

The 8th Earl of Granard (left) and “Kitty” Havemeyer (center) at the Newport Casino, ca. 1908. From the Newport Historical Society’s Henry O. Havemeyer Collection.

Among these new seasonal residents were artists and writers who sought inspiration from the glorious climes and worldly company. One such writer was Clement C. Moore (1779-1863), the author of the oft-memorized Christmas poem, A Visit from St. Nicholas. Although Moore did not write the poem in Newport (rather at his family estate in New York City), he was enchanted by the City-by-the-Sea and chose to spend summers and his final years here.

As always, Newport was developing itself in other ways. Not far from the homes of the up and comers of East Coast society, military men busily toiled in the fortif

ications constructed after the Revolution to make sure such a sacking would never harm the city or state again. While a series of fortifications were constructed, it is Fort Adams, opened on July 4, 1799 and named for our second (and sitting) president, which remains most prominent. Ultimately it housed nearly 470 mounted guns; though it was never tested in war, its casemates and earthworks were in many ways obsolete not long after they were finished. Through World War II, soldiers manned Fort Adams as a point of strategic coastal defense against possible invaders from air and sea.

After the Civil War, an influx of African American settlers from the South, in particular from Culpepper County, Virginia, continued Newport’s history of being a destination for entrepreneurial immigrants. Coming to Newport at first to work on the steam ship lines, these men and women took advantage of the growing summer visitor economy to create businesses: restaurants and catering, carriages and taxis. Newport’s economy became seasonal, focused on those who poured into the city each summer from Boston, New York and Philadelphia. Soon, the very wealthy from New York began to build summer homes here. As the Gilded Age was born, Newport reinvented itself once again.

Vanderbilt, Berwind, Morgan and Astor became names associated with the once subdued seaside city. Not interested in roughing it, the men and women of such families set about building magnificent “cottages” in which they lived and entertained for only weeks a year. The presence of these families and those like them attracted international attention and visitation. And as Rhode Island’s economy climbed to lofty heights in the 1890s and 1900s, Newport became the playground to Providence’s business and industrial capital. Though different in character and culture, these two cities both sat atop the nation in reputation and wealth.

While Newport might have been a location of leisure for the upper crust, social events were not the only outlet for its competitive spirit. Sport found a grand stage here, as well. In fact, American tennis championships began in Newport not long after the Civil War, the tourney first played on the grass courts of the Newport Casino in 1881. While the championships left Newport in 1915, the Casino hosted its invitational until 1967— and matches continue to this day. But in 1883, it was sailing that took hold of Newport’s imagination and population. When the New York Yacht Club held its first annual regatta in Newport Harbor, a partnership that has lasted more than one and a half centuries was born. Newport further established itself the sailing capital of the world when it hosted the America’s Cup races for 53 years until 1983. And, certainly not to be overlooked, on October 4, 1895, the U.S. Open Championship was played on a nine-hole course at the Newport Golf and Country Club.

As the Gilded Age came to an end, the sport of yachting in particular remained a component of Newport’s character. But the city continued to evolve and reinvent. Between the world wars, Newport became a center for maritime innovation and production through the Torpedo Station and the Navy. Ultimately the largest civilian employer in the whole state, the Torpedo Factory was the result of a program of research and development in military technology that was centered here. It employed men and women from all walks of life. When it closed in 1951, following by a decreased Navy presence, Newport again needed to reinvent.

By this point, it was the American middle class that ruled the day. The concept of summer vacation had taken hold and Newport was quickly able to capitalize on the seasonal climate that had been attracting visitors since the early 19th century. Forward thinking individuals, such as Doris Duke and Katharine Warren, looked to the city’s past for inspiration. By protecting the historic fabric of the city, they allowed visitors to see not a replicated historic town, but rather a working historic city. With layers of history mingled with shops, restaurants, libraries and museums, the exclusive City-by-the-Sea was now open to all.

Tourism and its related service economy have helped reinvent and sustain the city in the face of an industrial and military void since the 1970s. But what happens when the economy changes again? What can we look to in our past to help show us the way?

While Newport can be seen reinventing itself again and again over the past four centuries, some things are constant. It has not been insular — its life has been intimately connected to the rest of the world though immigration, trade and the military. It has also always found its best success in leveraging its ocean-based assets: the port, the climate and the beauty of the sea itself. As we think about our future, and the need to respond yet again to a changing world, this history can be both informative and inspirational.