This guest post was written by Art Historian Astrid Tvetenstrand, whose recent research at the NHS was supported by the New England Regional Fellowship Consortium. Astrid’s research topic is ‘Seasons as Verbs: Nineteenth Century Landscape Painting and the Creation of American Second Home Culture.’

William Trost Richards (1833-1905), Untitled, ca. 1860, watercolor, 78.2.1, Courtesy of the Newport Historical Society

Paintings and postcards of Newport, Rhode Island consistently promote issues of exclusivity, excess, and beauty. The circulation of these images throughout the late nineteenth to early twentieth century explains how people conceived of this opulent summer colony. Pairing formal painting with commercial postcards poses an interesting intervention into art historical scholarship about Newport. By bringing together the stylistically elite with the colloquial, similar aspects of the region remain heralded for their aesthetic value.

This process of visual consumption is comparatively articulated through two pieces in NHS’ collection. A painting by regionally famed landscape painter, William Trost Richards (1833-1905), expresses aspects of landscape which held value for the artist and seasonal resident. A home sits sheltered by large foliage, representing the value nature held for the homeowner. A sweeping expansive view of the ocean contrasts the residence, suggesting the views from this home were impeccably coastal. The painting generates an interesting placed based story surrounding Newport. Art, architecture, and landscape coexist in Richards’ work in order to display distinctive physical features of the city.

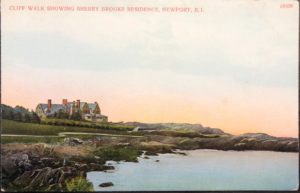

Cliff Walk Showing Sherry Brooks Residence, Newport, RI, ca. 1907, postcard, Courtesy of the Newport Historical Society, Postcard Collection, Box 3

Comparatively, this postcard of the Cliff Walk showing Sherry Brooks residence articulates a similar narrative. Much like the Richards’ painting, the home is picturesquely represented and shown with a distinctive connection to the ocean and its view. With nothing else in frame, the home sits commandingly over the rocky landscape. Promoting exclusivity, these two images suggest these viewscapes and the beauty of Newport was only available for the homeowner. Questions regarding access to these homes also is brought into the conversation as each structure is framed by natural features which render them isolated and obscured in the image. These two pieces from Newport Historical Society’s collection allow investigations into the connections between land, art, access, and value. These intersecting mediums point to the varying ways images can tell stories and what they can reveal. We can move beyond a pretty picture and see issues of nineteenth-century economics through looking at these two images. This process creates a more contextual history of Newport that brings forth new perspectives on American art.