Alexander Bice, MA graduate, Northeastern University, is one of the 2021 Buchanan Burnham Fellows working on capturing data from the NHS archives on Black and Indigenous people of color in colonial Newport, Rhode Island. The following post relates to the failed pension application for Caesar Babcock, an enslaved man who served in the Revolutionary War as a substitute for his enslaver, Hezekiah Babcock.

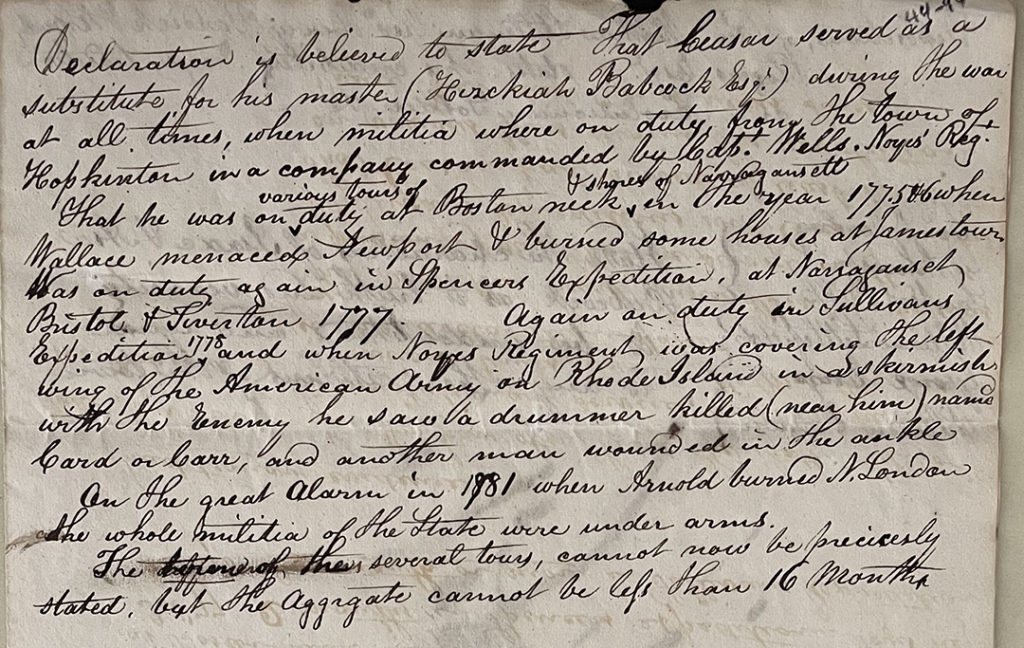

Caesar Babcock was one of many enslaved people who fought in colonial militias that were called to duty during the Revolutionary War.1 Some enslaved people volunteered but many were forced by their enslavers to fight in their stead for whichever side the enslaver supported. Enslaved people who fought in the Revolution were promised their freedom, but there were always risks that those promises would not be kept or that they might fight for the losing side and thus remain enslaved at the end of the war. In Caesar’s case, he served as the substitute for Hezekiah Babcock, his enslaver, in a regiment in the Continental Army. He served in several expeditions in Rhode Island as well as on the fortifications at the neck of Boston. For part of his service, he was in the Noyes Regiment and saw a drummer killed as part of a skirmish.

The first page of Caesar Babcock’s pension application. Caesar’ served as the substitute for Hezekiah Babcock in a regiment in the Continental Army. Box 44A, Folder 6. NHS Collection.

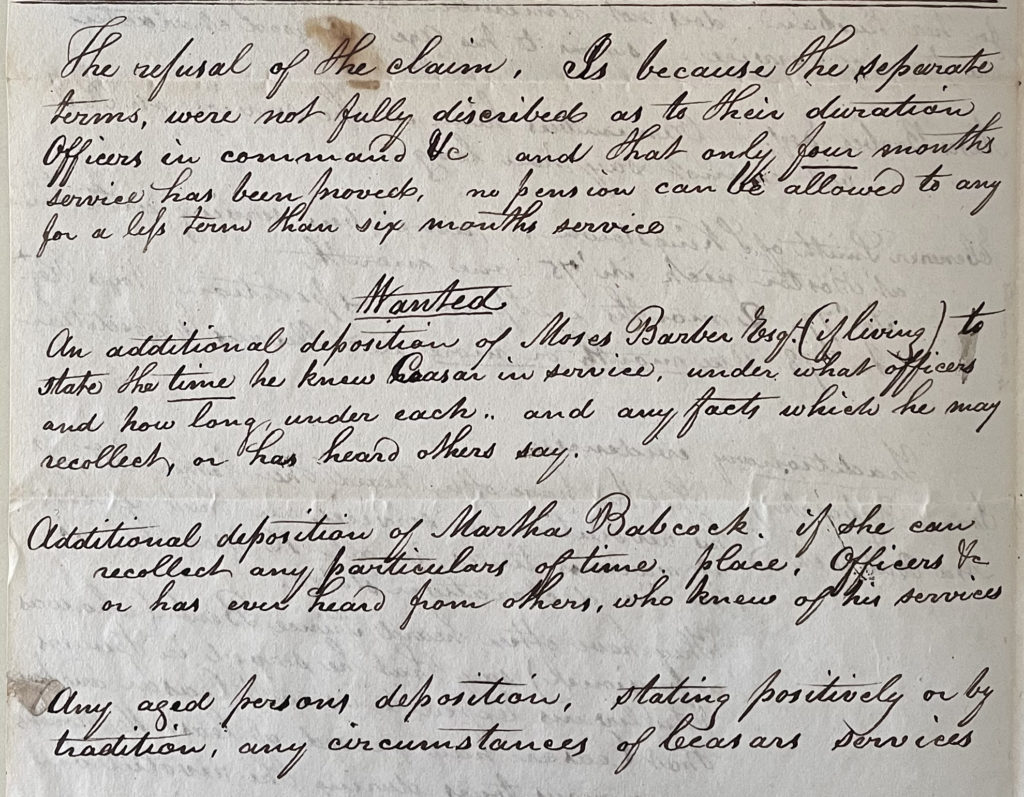

In 1832, Congress authorized pensions for those who served at least six months in a militia or the Continental Army.2 Those who fought in the war could apply for and receive a pension as long as they proved they had fulfilled the six month service requirement. Caesar Babcock petitioned for a pension in 1834, but was refused for not fully describing the duration of his terms of service and the officers in command.

Caesar Babcock petitioned for a pension in 1834, but was refused for not fully describing the duration of his terms of service and the officers in command. Box 44A, Folder 6. NHS Collection.

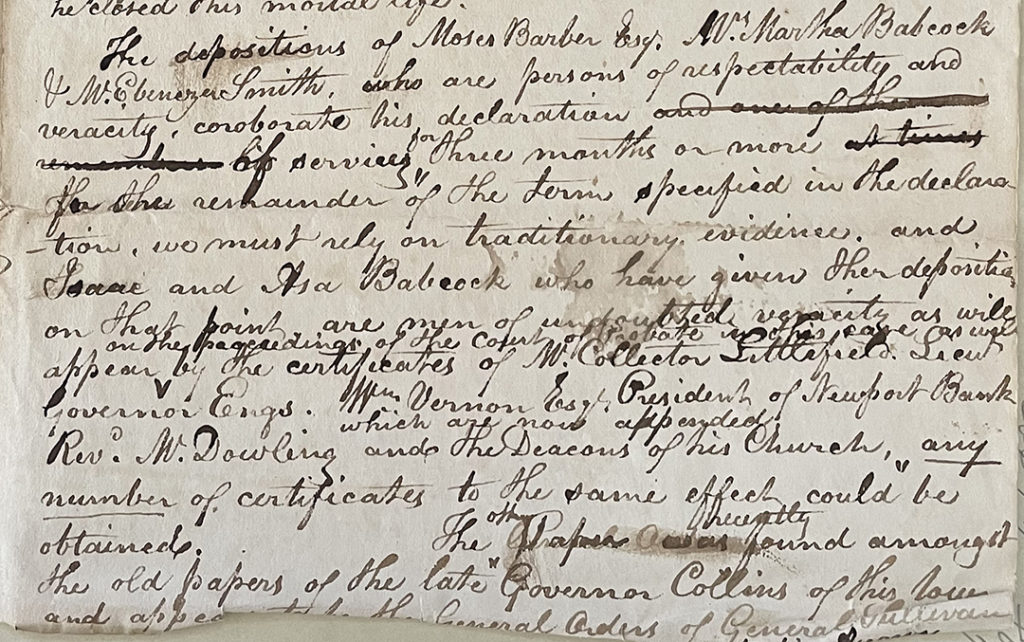

What the judge wanted -documentation with descriptions of time served and the officers in charge- would have been especially difficult to obtain for a previously enslaved man who was the substitute for his enslaver. The Caesar Babcock pension appeal, filed in 1837 after Caesar’s death, was the final attempt by family members to obtain the pension that Babcock was owed for his service. Being unable to furnish written records, the family interviewed several people to attest to Babcock’s service. These people included Martha Babcock (widow of Hezekiah Babcock), fellow pensioners Moses Barber and Ebenezer Smith, and Caesar’s sons, Issac and Asa Babcock. The most important part of the appeal was testimony from Isaac and Asa, who stated hearing from their father and a fellow pensioner named Prince Bent that Caesar had served at least 16 months in total. Unfortunately for the family, Prince Bent died before the pension was filed and thus, he could not testify on Caesar’s behalf. Several people attested to the truthfulness of Isaac and Asa, including the Lieutenant Governor of Rhode Island, George Engs.

Several people attested to the truthfulness of Isaac and Asa Babcock’s testimony, including the Lieutenant Governor of Rhode Island, George Engs. Box 44A, Folder 6. NHS Collection.

The family estimated Babcock’s service at 16 months, however the judge in charge of the appeal ignored this estimate and the attestations of those claims. The evidence and testimony of Isaac and Asa was thrown out. Instead, the judge accepted only the four months clearly described by Ebenezer Smith in deposition and awarded no money to the family for their father’s service. Even if the War had been an avenue of freedom, it did not guarantee equal treatment for Babcock or his family. That Caesar’s family pursued the pension even after his death speaks to the importance placed on recognition from the government for his service as well as the ways that contributions of Black people were ignored or erased after the war concluded.

[1] Christian M. McBurney, “Freedom for African Americans in British-Occupied Newport, 1776-1779, and the ‘Book of Negroes,’” Newport History 87, no. 276 (2017): 2.

[2] Richard Peters, ed., “An Act Supplementary to the ‘Act for the Relief of Certain Surviving Officers and Soldiers of the Revolution,’” in The Public Statutes at Large of the United States of America, vol. 4 (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1846), 529–30.