Hampton Smith, Ph.D. student, MIT, is one of the 2021 Buchanan Burnham Fellows working on capturing data from the NHS archives on Black and Indigenous people of color in colonial Newport, Rhode Island. The following post relates to how, when exploring the histories of marginalized peoples, maintaining an awareness of those who recorded historical documents is just as important as knowing those who were recorded.

As 2021 Buchanan Burnham Fellows at the Newport Historical Society, we are working to document historically marginalized peoples within the NHS archive. By combing through the documents at our disposal, we are recording the existence of the Newport’s enslaved, indentured, and manumitted population in order to reconstruct their livelihoods out of previous obscurity.

In doing this work, we remain mindful that these documents are the by-product of an outlook that is wholly distinct from our own contemporary points of view. We are, in some instances, literally separated by over three centuries from the documents we are studying. It is therefore vital to understand who wrote these documents, how and why they were written, and the ways in which these documents can illustrate or completely omit the historical perspective of certain individuals. Especially when writing histories of marginalized peoples, we, as researchers, must ask how documents can obscure and reveal the stories and memories of previously underexamined peoples.

Deposition by Nathaniel Waterman, resident of Providence, recounting his knowledge of the tribal sachems of Rhode Island. FIC.2020.126, NHS Collection.

I recently turned to transcribing documents pertaining to interactions between indigenous peoples and English settlers across the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. An example of one such document is a deposition dated to February 6, 1705, in which Nathanial Waterman, identified as an interpreter who “was often employed to interpret the disputes and debates between the English and the Indians”, narrates a genealogy of the Narragansett peoples. Through this deposition, Waterman testifies that “Canonicus,” a sachem, or tribal leader, has three nephews, “Miantinomy, Mosup, and Cogonoquant.” Waterman further notes “Canonicus’s” son, “Moaxam,” had two sons, “Scuttup and Waquaquonuto” that would later become sachems as well. After narrating the family tree of “Canonicus,” Waterman ultimately describes the gifting of land to “Nonoganit,” a Narragansett tribal member, for being courageous in a mission involving Pequot peoples.

This document contains a wealth of information. We learn of an entire genealogy of tribal leaders and an example of how land was granted to individuals within the Narragansett community. But as much as this document records indigenous actors and practices, it also historicizes the specific point of view of Nathanial Waterman, the translator and recorder.

Written sometime between 1705 and 1706, Waterman’s deposition records an event that happened sometime within the prior 50 years. While this document is dated, the actual event it describes is not. The deposition is a second-hand account of the motives, thoughts, and practices of the indigenous actors. We know little from their perspective. Instead, this document records how Waterman translated a story of indigenous peoples. It is a memory–mediated across time by his hand alone. This document therefore captures a specific historic instance, but must be handled with caution and in dialog with other sources, especially those authored by indigenous people.

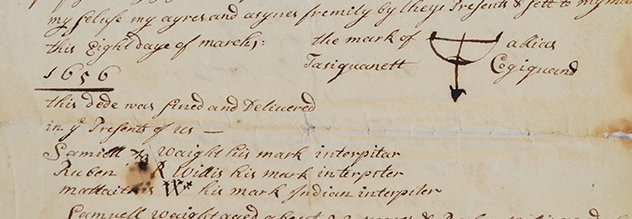

While Waterman’s document records a narrative about a specific land transaction, other documents are land deeds authored by both indigenous peoples and English settlers. Sometimes they even index an indigenous person’s unique way of identifying themselves. For example, on a deed from 1656, the mark of “Tasiquanett, whose alias was Cogiquand” is listed above the mark of “Mattaithis”, an “Indian interpreter.” These signatures are unique; they index agency and individuality. And while in hindsight we know many of these deeds were explicitly uneven trades or may have been based on different understandings of the nature of the transaction, these historical marks nevertheless matter: they communicate presence and agency, skill and ability, loss and survivance.

The mark of “Tasiquanett, whose alias was Cogiquand” is listed above the mark of “Mattaithis”, an “Indian interpreter.” Box 126, Folder 4, NHS Collection.

These documents briefly illustrate how as researchers, maintaining an awareness of those who recorded these historical documents is just as important as knowing those who were recorded. Especially when attending to histories of marginalized peoples, we have to be willing to hold together the many layered complexities within and outside the archive.

Mindful of the opportunities these documents provide, it is worth underscoring that Indigenous people have and tell their own histories. We have to attend to indigenous voices and ways of knowing. As a non-indigenous, white scholar, I hope and urge you to look towards indigenous peoples – the art they make, the museums they cultivate, and the histories they preserve – to better understand our shared histories.