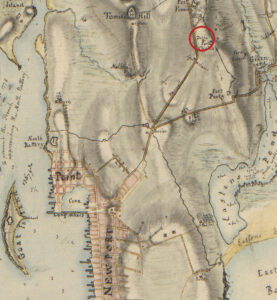

Location of the Dudley’s residence, marked in red, overlayed on a 1775 map of Newport. William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan Library Digital Collections, ID 828.

Charles Dudley (1737-1790) was appointed Newport’s customs collector in 1768. 18th century customs officials received both a generous salary and a percentage of their collection, and since Newport was one of North America’s busiest ports Dudley quickly built a fortune, and was sometimes derisively referred to as “Lord Charles Dudley” among colonists. During the imperial crisis, Dudley sided with the King in whose government he served, becoming a leading voice among the Loyalist faction. Still, he could be more forgiving than many royal taxmen. In several cases, he assigned lax fines or allowed merchants to re-purchase seized cargos at discounted rates. Likely, these dealings further enriched the already-wealthy Dudley. Despite being reviled by many for enforcing the King’s laws, Dudley’s actions reflected long-standing relationships with the town’s mercantile community, including Aaron Lopez, who frequently consulted with Dudley on economic and political matters.

Dudley married into a long-standing elite Newport family in 1769 when he wed Catherine “Kitty” Crooke (1750-1800). The Crookes were a large mercantile family whose lineage also included several prominent Rhode Island politicians. Charles and Kitty built a large manor house near Middletown, Rhode Island, where the couple lived in luxury. Their household included at least two enslaved people, one of whom, Polydor, is referenced frequently in letters between Charles and Kitty during 1775.

While from all accounts a love match, Charles Dudley was likely one of the most eligible bachelors in the region, and he acquired lucrative new connections through his alliance with the mercantile Crooke family. And while Charles’s official position forced him to publicly side with the British government, Kitty could keep her loyalties more flexible.

List of suspected Loyalist, 1775. Rhode Island State Archives.

As Rhode Island’s revolutionaries seized control of the colony over the summer of 1775, Charles Dudley maintained his loyalty to his King, an attachment for which he would suffer much. News of developments like the Siege of Boston, the Battle of Bunker Hill and – closer to home – the coup against Governor Joseph Wanton, Sr. must have dismayed and frightened the tax collector, who feared the fate of other colonial officials who fell into the hands of Patriots. Although Newport’s Patriots were relatively tolerant of those with Loyalist leanings, revolutionary committees in other colonies began to take action against Loyalists almost immediately after war broke out, disarming and even imprisoning some deemed threats to the new order. Charles Dudley certainly fell into that camp. Although Charles Dudley’s valuable estate and family connections bound him to Newport and in other circumstances may have swayed him to the Patriot side, his duty to his King demanded he oppose the revolutionaries – who he viewed as illegitimate rebels – in any way that he could.

Dudley’s crisis came in the fall of 1775 when a messenger arrived from Rhode Island’s revolutionary government demanding that he surrender a chest of customs money held in trust for the British government. If he refused, the revolutionaries threatened to imprison him and confiscate his property. In response, Dudley fled his home with Polydor and took refuge aboard HMS Rose, a British warship stationed in Newport Harbor. Thinking that her husband’s absence would be a matter of only weeks or months, Kitty Dudley remained at the couple’s home to manage the family’s affairs until Charles could return. Her presence also served to protect the family’s claim to their extensive property. Charles, however, would never again set foot in Rhode Island, and the couple would not see each other for four years.

Charles Dudley remained on board HMS Rose through the blockade and bombardments of 1775 and early 1776, often dining with Commodore Wallace and other British officers. As he languished at sea, Dudley dispatched letters to his superiors in London as well as the British commanders-in-chief in Boston and Halifax, reporting his situation and pleading for aid. In this, his experience was similar to many other colonial officials forced to flee aboard Royal Navy vessels, including not least the governors of New York, Virginia, and Georgia, with whom Dudley also corresponded during his naval sojourn. Dudley may even have encountered his former acquaintance Martin Howard at sea – Howard, a former Newport attorney forced to flee during the Stamp Act Crisis, had secured appointment as chief justice of North Carolina but fled his home a second time in 1775 at the outbreak of hostilities in that region. As he networked with the growing number of ousted imperial officials, Dudley contemplated whether to wait for his superiors to intercede or to go in person to London to plead his case.

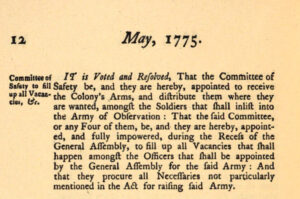

Committee of Safety authorized by act of the General Assembly May Session, 1775. University of Michigan Law Library.

On land, Kitty Dudley faced the wrath of Rhode Island’s revolutionary Committee of Safety, which quickly impounded the couple’s estate and, when it became clear that Charles had no intention of surrendering the customs money he held, began to confiscate their property to sell for the benefit of the revolutionary cause. While the revolutionaries claimed ownership of the Dudleys’ property, they allowed Kitty to keep a few personal items, continue living in their house and retain custody of their enslaved people. Kitty’s family’s ties to the Patriot side allowed her a degree of grace, however, her husband’s departure had left her in a precarious position.

The Committee of Safety sold off the rest of the Dudleys’ property, including valuable farmland and rental properties as well as horses, carriages, agricultural implements, and the imported luxuries that upper-class colonists possessed. While family friends bought a few items for safekeeping, Kitty reported that many of the items sold for far less than their worth. The Dudleys’ fine feather bed went to Continental General Charles Lee, a welcome gift from the town’s revolutionary leaders. While the rest of Newport faced the threat of losing everything in a bombardment, the Dudleys lost most of what they had at the hands of the revolutionary government.

In March, 1776, Charles departed Boston for Halifax, en route to England, leaving Kitty in Newport. Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society (1880-1881), Vol.18, p. 266.

In the winter of 1775-1776, Kitty and Charles Dudley decided to divide their efforts to recoup their losses along political lines. While Charles determined to travel to England – departing via Halifax in early 1776 along with the deposed royal governors of Georgia and South Carolina – Kitty remained in Newport in an attempt to recover the couple’s property and curry favor with the revolutionary government. Kitty Dudley’s position as an elite woman and family connections among the Patriot side – many of her Crooke relations supported the Revolution – afforded her a degree of courtesy not granted to her husband. The couple hoped to leverage Kitty’s position in Newport to make inroads with the new regime even as Charles pled their case before the royal government in London.

Such strategies were pursued by many families in Newport and around the rebelling colonies. Benjamin and Mary Almy, with whom the Dudleys were likely acquainted, also split along political lines, although in their case the husband, Benjamin, joined the Continental Army’s artillery corps while the wife, Mary, declared loyalty to the crown and aided the British occupation of Newport (1776-1779). During the battle of Rhode Island, the couple found themselves on opposite sides of a deadly conflict, as Benjamin participated in a failed French-Continental assault on Aquidneck Island. Despite the strain the war put on their marriage, however, the Almys re-united afterwards, and the depth of Mary’s loyalism remained hidden for nearly a century. Whether a deliberate strategy or an honest ideological difference, the Almy’s divided loyalties allowed the family to successfully hedge their bets as the outcome of the war hung in the balance.

While the Almys prospered after the war, the Dudleys’ efforts to make good mostly failed. Kitty Dudley never recovered the family’s lost property or received any compensation, and eventually wore out her welcome with the revolutionary authorities. After three years apart and having lost nearly all their land and property, she joined Charles in London in 1779, where she gave birth their only son, Charles E. Dudley, in 1780 or 1781. While the Dudleys received some compensation from the British government for their losses in Newport, they never recovered their pre-war wealth or status, and lived in quiet obscurity in England until Charles’s death in 1790. Sometime afterwards, Kitty and their son returned to Newport, where Kitty Dudley died in 1800. The record does not indicate what happened to Polydor and their other enslaved people after the family relocated to London.