This guest post was written by historian Joseph Weisberg, whose recent research at the NHS was supported by the New England Regional Fellowship Consortium. Joe is a PhD student at Brandeis University; his provisional dissertation thesis is “How Slavery and Jewish Life Shaped Each Other: Understanding the Lopez Family and Their Multigenerational Legacies of Slavery and Jewishness.”

Aaron Lopez’s blotter, or waste book, entry for December 16, 1772 is relatively typical of an eighteenth-century merchant.[1, 2] He sold foodstuffs, fabrics, nails, and other items that circulated through Newport, including chocolate he brought to and received from the Black chocolatier Prince Updike; conducted business; and recorded a memo about oak staves that he took for one of his ships. However, one entry distinguishes Lopez’s blotter from those kept by most merchants in Newport. Lopez recorded three expenses under the heading “Sedakah” (Hebrew for charity), including one for a “bottle [of] sweet oil for Hanukah.”[3] While the details of the transaction are not entirely clear, the implications are: Lopez was provisioning oil for the upcoming Jewish holiday.

A bill from Lopez to Samson Mears in St. Eustatius for portage of “1/4 cask matze [matzah]”. Box 164, folder 3, Collection of the Newport Historical Society.

It is well known that Lopez, who was born a Portuguese converso and reclaimed his Jewish identity in North America, traded in Jewish articles like kosher meat and matzah.[4] However, Lopez’s account books and correspondence also preserve records of his extensive dealings with Christians, and his willingness to handle items like pork and shellfish complicate any impression that discomfort with non-kosher merchandise set the boundaries of his business. We might ask, then, how Jewish was Aaron Lopez’s mercantile operation? The answer to that question requires more than tracking the religious identity of people who traded with Lopez or classifying the items in account ledgers as treifah or kosher. The ebbs and flows of the Jewish calendar could affect a wide range of people—Jewish and non-Jewish, free and unfree, merchant and laborer—who depended on Lopez.

Nicholas Brown & Co. to Aaron Lopez, Providence, 6 September 1766, Box 168, folder 3, Collection of the Newport Historical Society.

When Nicholas Brown of Providence tried to call on Lopez in September 1766, he found that Lopez was unavailable. His company sent a letter a few days later explaining the circumstances, “Our NB [Nicholas Brown] was in Newport a few Days ago & Called at your store with Design of taking any articles you might have that we wanted, but it being your Holiday Prevented [it].”[5] The timing of the letter suggests that Brown had the misfortune of calling on Lopez during Rosh Hashanah, which ended the previous day. As a result, Brown lost out on the benefits of doing business in person. Lopez’s absence for Rosh Hashanah turned what could have been a relatively easy transaction into a more complicated endeavor where Brown had to speculate about what goods Lopez had and on what terms he might sell them. Of course, the final price of the transaction could not be immediately determined since Brown was not sure which items he would receive. These complications could have been avoided if Brown had called on Lopez before the Jewish New Year.

Annual events like Rosh Hashanah were not the only aspects of Jewish time that affected Lopez’s network. A series of letters from Aaron Lopez’s nephew David make clear that Shabbat influenced the flow of information on a weekly basis. In one letter, David Lopez apologized for his penmanship but was confident that his “Dear uncle will pardon it rather than I should Transgress the Sabath to coppy it.” The date of the letter—December 29 fell on a Friday in 1780—removes any doubt that David referenced a Jewish rather than a Christological notion of the Sabbath. Other letters more clearly establish the Jewish character of David’s shabbat observance.[6] He dated one letter, “Fryday half past 5 oclock PM” and subsequently explained his brevity, “It being now too late to enlarge [the letter] without Trespass[in]g on the Saba.”[7] Of course, David wrote to his uncle throughout the week, but the remnants of his letters sent on Friday afternoons preserve a record of how the weekly rhythms of Jewish life could influence the flow of information through Aaron Lopez’s network.

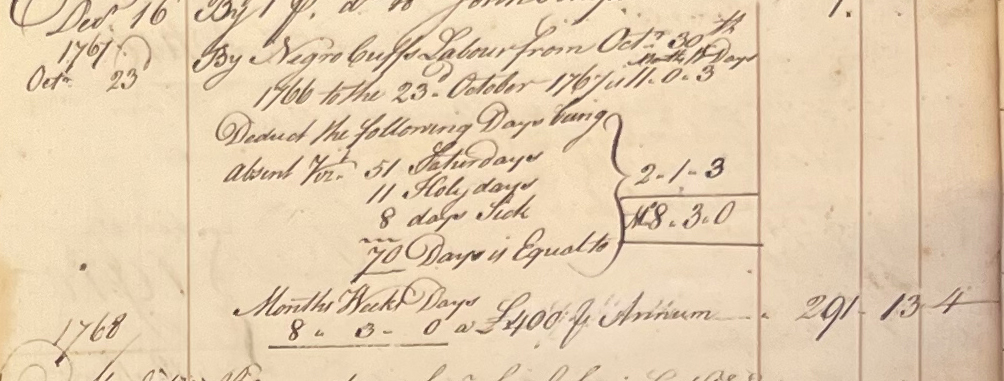

The weekly and annual rhythm of the Jewish calendar influenced more than just the merchant class. Enslaved people found their work schedules set according to their enslavers’ religious observance. Aaron Lopez often “hired” workers who were enslaved by other Newporters, which means that historians can reconstruct aspects of these people’s lives by carefully reading Lopez’s account books. For instance, Lopez’s account with Katherine Pinnegar shows that he hired an enslaved man named Cuff for nearly a year beginning on October 30, 1766. The next line in the account books shows that Cuff was absent on 51 Saturdays, 11 “Holy days,” and 8 sick days. In other words, Cuff never worked on the Jewish Sabbath during the year he was employed by Lopez.[8] Although it might be tempting to read Cuff’s off days as evidence of Jewish religious observance, it is unlikely that he adopted Judaism as his own religion. Enslaved people in Newport generally did not convert to Judaism or the liminal status of “slave of Israel” (eved israel).[9] Equally important, records show that an enslaved Newporter named Cato was absent on annual Jewish holidays as well as non-Jewish occasions like Christmas and Election Day.[10]

Lopez tracked Cuff’s absences, indicating Cuff was absent on 51 Saturdays, 11 “Holy days,” and 8 sick days. Lopez Account Book N, Vol. 555, fol. 98, Collection of the Newport Historical Society.

When I shared an earlier draft of this post, multiple colleagues asked me about the possibility that enslaved people who worked for Lopez and did not labor on Jewish holidays may have received more time off than people who labored for Christian enslavers. Unfortunately, the question is difficult to answer because knowledge of people like Cuff and Cato reaches me through Lopez’s account books. Aaron Lopez kept accounts of Cuff and Cato’s work schedules because they affected his business, but his mercantile records do not account for what they did when they were not under his supervision. It is well within the realm of possibility that Cuff and Cato’s enslavers found other ways to exploit their labor when they were not working for Lopez.

However, the possibility that Cuff and Cato may have experienced Jewish sacred time as additional time off from work remains alive until I locate materials that shed light on what happened when they left Lopez’s ambit.[11] Additional time would have been a valuable commodity for enslaved people because it would have allowed them to work for their own account, rest, enjoy leisure activities, or spend time with their families.[12] In other words, my colleagues asked whether being enslaved by or hired to a Jewish enslaver like Aaron Lopez held the possibility of marginally improved material conditions for enslaved Newporters. As I continue my research, I hope to understand the historical intricacies of how Cato and Cuff interacted with Newport and its Jewish community. For now, I can show how Lopez’s Judaism influenced their lives. Where, when, and perhaps even what Cuff and Cato did on a given day depended on the cyclical patterns of the Jewish calendar.[13]

[1] I have made two decisions regarding spelling and terms that I should make clear. I reproduce direct quotations as closely to the original text as I can, including nonstandard capitalizations and spelling. I insert commentary in brackets where the meaning might otherwise be obscured. I follow the same guideline for names with the important exception that I have chosen to standardize names of historical figures who are generally known by a single name. For instance, I consistently refer to “Aaron Lopez” even though his contemporaries were not nearly as consistent.

[2] The Oxford English Dictionary defines a waste book, “A rough account-book (now little used in ordinary business) in which entries are made of all transactions (purchases, sales, receipts, payments, etc.) at the time of their occurrence, to be ‘posted’ afterwards into the more formal books of the set.” Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “waste-book (n.),” July 2023, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/6820502846.

[3] Store Blotter Commencing December 14, 1772, Newport Historical Society, Vol. 462.

[4] Examples of Lopez trading in Jewish article include Stanley F. Chyet, Lopez of Newport: Colonial American Merchant Prince (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1970), 134-135, 188-189; Laura Arnold Leibman, Messianism, Secrecy, and Mysticism: A New Interpretation of American Jewish Life (Vallentine Mitchell: London, 2012), 185-187, 191. I found at least one example in the NHS collection. Box 164, folder 3 includes a bill from Lopez to Samson Mears in St. Eustatius for portage of “1/4 cask matze [matzah]”

[5] Nicholas Brown & Co. to Aaron Lopez, Providence, 6 September 1766, Box 168, folder 3, NHS.

[6] David Lopez to Aaron Lopez, Providence, 29 December 1780, box 169, folder 3.

[7] David Lopez to Aaron Lopez, Providence, 22 September 1780, box 169, folder 3. These letters belong to a larger genre of colonial Jewish letters that reflect strict Sabbath observance. See American Judaism: A History, 2nd edition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), 23.

[8] Lopez Account Book N, Vol. 555, NHS, fol. 98.

[9] Leibman, Messianism, chap. 3 (especially pp. 92-96, 107-113)

[10] Lopez Account Book N, Vol. 555, NHS, fol. 69.

[11] I use this post to explore different possibilities of how Cato and Cuff may have experienced Jewish holidays. I am actively researching the topic and wanted to share a snapshot of my current progress. My understanding should change as I continue researching. For instance, I hope to gather more evidence about the specific conditions of their hire, which may shed light on how much Cuff and Cato engaged with their enslavers on a day-to-day basis.

[12] Scholars of slavery in New England have taken note of the different ways that enslaved people experienced pleasure. Jared Hardesty argues that taverns were an important space of association for enslaved people: “Not only were they spaces where people could have a drink and some food to eat but they also hosted entertainment in the form of live music and dancing, provided an opportunity to hear the latest news and gossip, and allowed people to play games and gamble.” Lorenzo Johnston Greene provides a broader survey of what he calls “slave amusements.” Enslaved Newporters seem fit the regional trend. Tara Bynum describes a pig roast that Cesar Lyndon hosted in 1766, and Cuff was once absent from Aaron Lopez’s employ “being gone to Horse Race.” See Jared Hardesty, Black Lives, Native Lands, White Worlds: A History of Slavery in New England (Amherst: Bright Leaf, 2019), 103; Lorenzo Johnston Greene, The Negro in Colonial New England, 1620-1776 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1942), 245-256; Tara Bynum, “Cesar Lyndon’s Lists, Letters, and a Pig Road: A Sundry Account Book,” Early American Literature 53, no. 3 (2018): 843-45; Lopez Account Book N, fol. 69.

[13] I thank Rafael Abrahams and Joseph Yauch for encouraging me to write the final two paragraphs of this post.