This is a guest blog post by Rebecca Farias, MA in History, Providence College. Rebecca is a 2022 Buchanan Burnham Fellow, contributing towards the “BIPOC Biographies from the Archives of the Newport Historical Society” initiative.

Newport’s turbulent history with privateering began in 1652. The eastern Long Island government (then under the purview of Massachusetts) chartered twenty Newport sailors to board ships and steal from the Dutch. The triumphant privateers took home “booty,” which they distributed among residents, but controversy ignited when the public discovered they had been following orders from outside Rhode Island.[1]

This balance between autonomy and authority reveals the line between privateering and piracy. Colony governments condemned pirates as domestic terrorists, as pirates seized property indiscriminately. Unlike pirates, privateers received a letter of marque from a government, assuring the coveted right to plunder other nations’ ships with a private vessel. Privateers were sometimes upstanding citizens, as was the case with brothers John and William Wanton. Like many of Newport’s able-bodied men during Queen Anne’s War (1702-1703), the Wanton brothers privateered for the British, against the French. The Wantons found particular acclaim, described by a 19th-century maritime historian as “among the ablest and most distinguished and successful privateersmen, considering their surroundings, that ever stood upon a quarter-deck to command a ship.”[2]

Privateers could find themselves in rocky waters if their parent nation changed allegiances while they were overseas, without their knowledge. Or, privateers with access to a ship, crew, and weaponry could transition into piracy. Privateering was a lucrative career, but piracy could grant more money and freedom. For context, Captain Thomas Tew, who roved Rhode Island’s waters, was valued by Forbes as the third-wealthiest pirate who ever lived, with his accumulated treasure worth an estimated $103 million dollars in today’s currency. He earned most of that fortune after abusing his privateering license through piracy.[3]

Even with the backing of the royal government, privateering out of Newport remained a cutthroat business. Consequently, letters of marque contained strict “articles of agreement” that “covenanted” the captain to his crew, and thus bound the entire “company” of sailors to the owners of the ship, the stakeholders, and most importantly, the government that commissioned the privateering.

The Newport Historical Society retains a letter of marque granted from Britain to a group of Newport privateers chartering Queen of Hungary, dated to July 1774. In 1744, the Spanish and French waged war against the Anglos and the Austrians. The Newport privateers aboard Queen of Hungary were meant to protect British interests by seizing cargo from the French and Spanish armadas. Queen of Hungary was “fit out,” or constructed, in Rhode Island, along with the following vessels: Saint Andrew, Triton, Revenge, King George, Duke of Marlborough, Brittania, and Queen Elizabeth, to name a few examples of British-backed privateer sloops constructed locally. Note that the naming of the ships corresponds to British royalty or other awe-inspiring, nationalistic entities, and that privateering vessels were also referred to as “privateers.” Queen of Hungary paid homage to Britain’s short-term allies. [4]

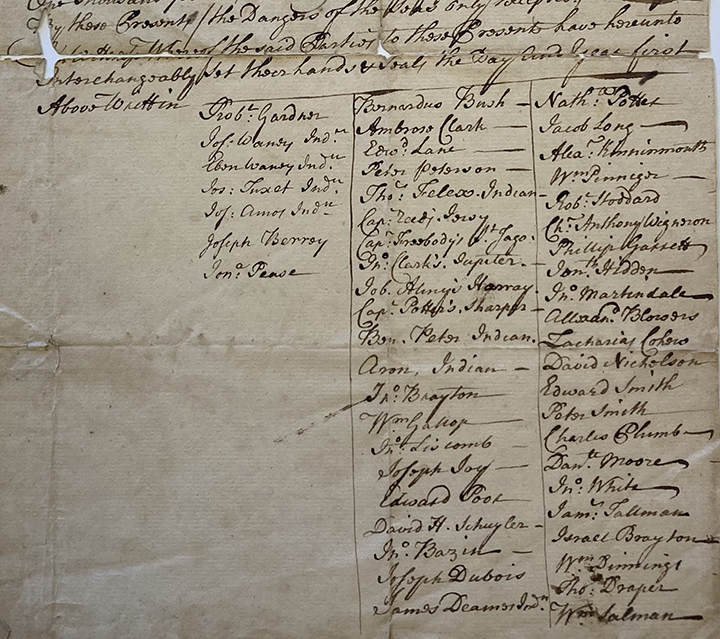

Signatories of the Queen of Hungary‘s Letter of Marque, dated to July 1774. Box 69 Folder 16, NHS Collections.

By examining Queen of Hungary’s letter of marque, granted to a group of Newport privateers that included Jonathan Tillinghast, Solomon Townsend, Samuel Freebody, and William Channing, historians can appreciate the commitment that the crew established to the captain. The company was bound to the captain, who made executive decisions. Likewise, the document’s articles of agreement show the detailed protections and regulations in place for sailors, including disability compensation and laws against fighting, stealing, and sexual assault against women.

If a person lost a “joint” (finger or toe) or a limb, they would be compensated: “If Any of the Company in any Engagement with the Enemies or true Service of the Voyage shall loose a Joint or Joints he shall have One Hundred Pieces of Eight and if he looses a leg or an arm he shall Have His Hundred Pieces of Eight or the Value Thereof in Goods or Effects Taken.” Rather than treating all of their prisoners poorly, the privateers agreed not to assault potential female captives for fear of losing their profits: “If any one of the Company behave indecently to any female prisoner he shall forfeit his Share to the Company.”[5]

Another significant aspect of this letter is the list of the crew’s signatures at the bottom of the document. Out of the fifty crewmembers, eight were Native American; each of their names are listed alongside the racial qualifier “Indian”. The prominent presence of Native American or African American sailors is not unique to Queen of Hungary, as minoritized sailors often took to the sea because of offers of fair pay, unlike most jobs on land.[6] Some of the crew members also brought their slaves with them, as seen in this list of crewmen: “Captain Freebody’s Jago” and “John Clarke’s Jupiter,” for example.[7]

The severity of these articles shows that privateers experienced life-threatening situations, similar to pirates. Privateering, while more acceptable than piracy, was not a position without risk of bodily harm. Articles of agreement served as safety nets, but privateers still faced the uncertainty of seafaring life. Privateering did not even ensure a profit: out of the records examined, it appears that Queen of Hungary only seized one enemy ship- a sloop off the coast of Newfoundland in October 1744. Perhaps this company was not the richest or most successful. But this letter of marque reveals the complexity of Newport privateering and will remain invaluable to historians.[8]

[1] William P. Sheffield, Privateersmen of Newport, (Providence: Rhode Island Historical Society, 1882), 6.

[2] Sheffield, Privateersmen, 8.

[3] Top-Earning Pirates, (Forbes: 2008), https://www.forbes.com/2008/09/18/top-earning-pirates-biz-logistics-cx_mw_0919piracy.html?sh=5552397d7263.

[4] Edward Field, State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations at the End of the Century: A History, (Boston: Mason Publishing Company, 1902), 414.

[5] Letter of Marque for Queen of Hungary, Newport Historical Society Manuscript Collections, Box 69 Folder 16, (1744).

[6] Letter of Marque, Newport Historical Society Manuscript Collections, Box 69 Folder 16.

[7] According to census information collected by the Newport Historical Society for the Rhode Island’s BIPOC Heritage project, John Clarke lived with three unnamed Black people in 1774, assumed to be enslaved: two male children and one adult female. It is likely that one of these individuals is Jupiter. Jupiter was traditionally a name for male enslaved people, drawn from the ancient Roman god of the sky.

[8] Field, State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations at the End of the Century: A History, 414.