This is a guest blog post by Maureen Iplenski, MA/PhD in History, American Studies, Certificate in Museum Studies (expected 2026) University of Delaware. Maureen is a 2022 Buchanan Burnham Fellow, contributing towards the “BIPOC Biographies from the Archives of the Newport Historical Society” initiative.

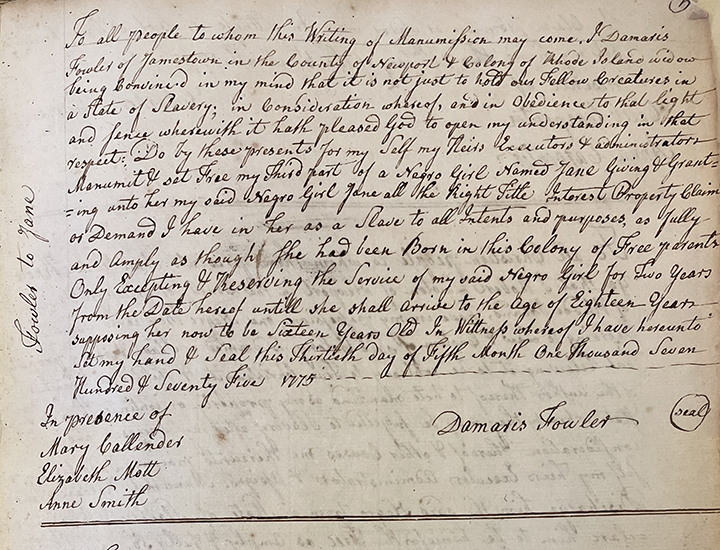

In May of 1775, Demaris Fowler, a Widow then living in Jamestown, renounced her former position regarding the issue of slavery. “It is not just to hold our Fellow Creatures in a State of Slavery,” she proclaimed. “It hath pleased God to open my understanding in that respect.” [1] Fowler presented her newfound belief to members of the Society of Friends (also known as Quakers) in Newport. In the previous month, Demaris requested to join the Society, however, her request was rejected. Those at the April Monthly Meeting of Women’s Friends announced that her “desire to come under our care arises from a religious concern, but as she is incumbered with a Slave, who is a part of the Estate left by her husband, [she] is refused.” [2]

At that time, an African girl, who went by the name Jane, was enslaved by Damaris. Jane was given to Damaris after the death of her husband; however, it is likely that she acted as Jane’s enslaver prior to becoming a widow. Damaris’ husband, Gideon Fowler, was a Merchant and Slave Trader based in Newport. According to the Slave Voyages Database, in 1767 Gideon transported 37 Africans from Africa to Barbados, where they were delivered to their “original owners”. The Newport Mercury also announced that Gideon departed Rhode Island for Africa in June of 1768. These journeys required him to be at sea for years, during which time Damaris may have overseen Jane.

In order to join the Society of Friends, Damaris promised to free Jane. She granted Jane “all the Right, Title, and Interest [she had] in her…as though she had been born in the Colony of Free Parents.” Jane, however, was not fully freed. She was to serve Damaris “until she shall arrive to the age of eighteen years.” As Jane was just sixteen at the time of her “manumission” she continued to labor for Damaris and her household for another two years.

Jane was only partially freed in another sense. According to the Manumission Record, Damaris only owned one-third of Jane. She, therefore, was just one of Jane’s enslavers. They too would need to manumit Jane. This division of property followed a common practice in English Common Law known as “Widow’s Thirds.” When a husband died without a will, the Widow was legally entitled to a third of his Estate – which included enslaved laborers. Jane’s other enslavers are not identified, though they are likely family members of Gideon.

Manumission Record of Jane (1775), NHS Society of Friends Records, Volume 821, Page 5, Collection of the Newport Historical Society.

The 1782 Census possibly reveals Jane’s fate. It identifies a woman named “Jane,” who was a “Free Negro” and head of household. She lived with two other “Black” individuals at this time.[3] Although we cannot confirm that this Jane is the same Jane who was enslaved by Damaris, it is important to note that a woman named Jane did not appear in Newport’s previous Census in 1774. At that time, Damaris’ Jane was completing her term of service – therefore, she would not be listed in the Census. She, however, was set to be freed in 1777 – after which point Damaris’ Jane could head her own household.

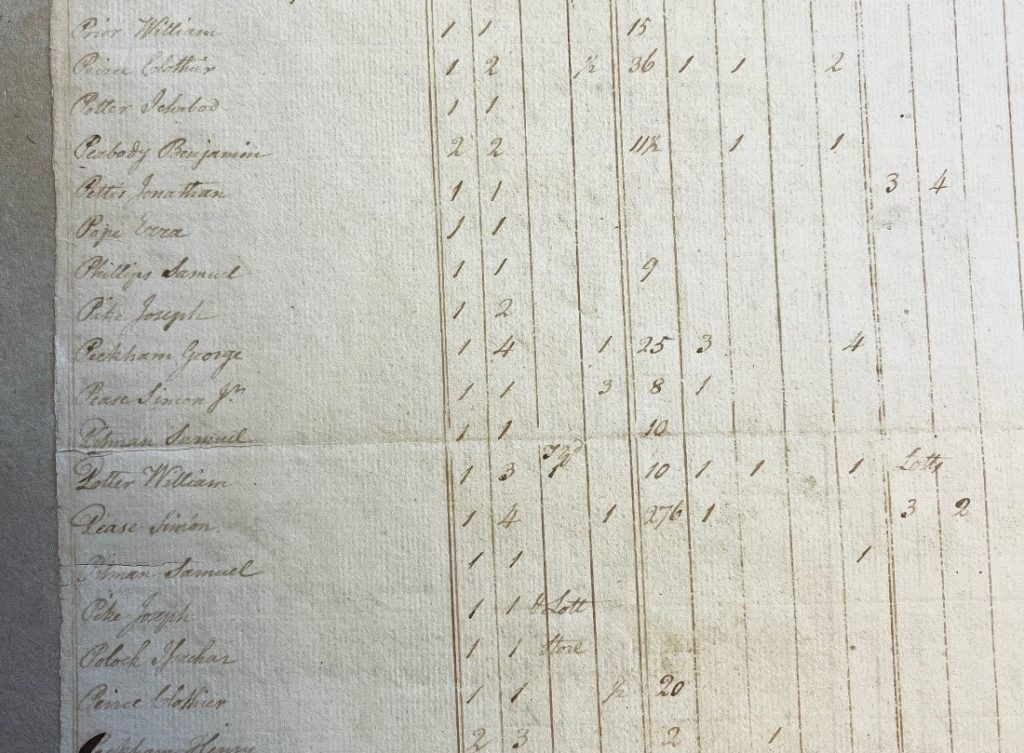

This practice of shared ownership of an enslaved person also occurred outside the law of “Widow’s Thirds.” For instance, the 1767 Newport Tax Records lists Clothier Pierce (Elder) and his son, Clothier Pierce Sr. as holding one-half of an enslaved person. This division was likely a financial decision as the two men may not have had the means to purchase an enslaved laborer with just their individual assets. In fact, upon the death of Clothier Pierce Sr. in 1780, it was revealed that he was deeply insolvent. According to Clothier Sr.’s Inventory, his assets totaled £11 and 16 Shillings, while his debts totaled £210 and 7 Shillings. He bequeathed this debt to his wife, Mary, who later petitioned the courts to sell Clothier’s real estate in order to pay his creditors. [4]

List of Rateable Estates (1767). Clothier Pierce and his son are listed on the top and bottom of this page. FIC.2022.101, Collection of the Newport Historical Society.

It is not known if the enslaved person claimed by Clothier Pierce (Elder) and Clothier Jr. was eventually freed, like Jane – or if they were kept in bondage. When Clothier Pierce passed, his assets were sold off. Therefore, his “half-slave” may have been sold to another enslaver.

In 18th century Newport, ownership of an enslaved person was often a sign of wealth.[5] Therefore, by sharing this ownership, the Pierce Family – along with others with less means – were able to access this enslaved labor. Damaris also demonstrated that even though she claimed just “one-third” of Jane, she maintained her authority to manumit Jane on her own terms. The practice of splitting ownership was just one method used by enslavers to keep Africans, African Americans, and Native Americans in a state of slavery

[1] Damaris Fowler, Manumission Record of Jane, May 30, 1775. Society of Friends Records, Volume 821, Collection of the Newport Historical Society.

[2] Monthly Meeting of Women Friends Held at Portsmouth, April 25, 1775. Minutes of Women’s Meeting, Society of Friends, 1759-1784. Collection of the Newport Historical Society.

[3] Jay Mack Holbrook, Transcriber. Rhode Island 1782 Census (Oxford, MA: Holbrook Research Institute, 1979).

[4] Clothier Pierce, Probate Records & Inventory, Newport City Hall, Volume 1, p. 137-38.

[5] Johnathan M. Beagle, “Waves of Change: Women, Work, War, and Wedlock in Colonial Newport, Rhode Island, 1750-1775″ (MA Thesis, University of Rhode Island, 1997), p. 69.