Masthead for The Newport Mercury, a newspaper produced by Solomon Southwick. Newport Historical Society.

Solomon Southwick (1731-1797) operated Newport’s only printing press during the imperial crisis and for much of the revolutionary era, publishing a weekly newspaper, the Newport Mercury, along with hundreds of the books, pamphlets, almanacs, and other printed materials that informed colonists and fueled political debate.

Born into a poor Quaker family, a wealthy patron paid for Southwick’s education at Philadelphia College (now the University of Pennsylvania), where he earned a B.A. in philosophy and mathematics in 1757. While engaged in his studies, Southwick likely read the latest texts of the European enlightenment, ideas from which inspired those on both sides of the Revolutionary War. Returning to Newport after graduating, he began his career working for a mercantile firm before purchasing the printing press from Samuel Hall in 1768 and commencing his career as a publisher. Likely, this change of career owed to Southwick’s courtship of wealthy twenty-one-year-old widow Ann Carpenter, who also happened to be the daughter of a former lieutenant governor. When Southwick wed Carpenter in 1769, she brought a sizable nest egg into their new family.

Southwick took the Patriot side early in the imperial crisis, participating in protests against the Stamp Act during the summer of 1765 and continuing to oppose taxation and reform throughout the 1760s and 1770s. He used The Newport Mercury to spread not just news and advertisements but also Patriot views, even adding the phrase “Undaunted by Tyrants” to the masthead in 1770. Southwick also published works by those supportive of royal authority. And despite his political views, through the mid-1770s Southwick gladly accepted government contracts to print customs forms, legislative proceedings, and other official documents. Indeed, in the 18th century, a printers’ business depended upon such contracts. In the 18th Century as in the 21st, newspapers served a vital public service but rarely made consistent profits.

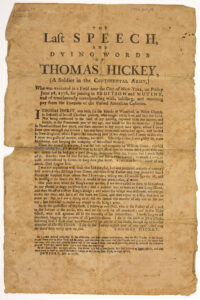

“The Last Speech and Dying Words of Thomas Hickey,” who was the first person to be executed by the Continental Army for mutiny, sedition, and treachery. Printed by Solomon Southwick, July 1776. Newport Historical Society, FIC.2025.036.

In the wake of Lexington and Concord, Southwick played a vital role both in spreading news and in organizing the military mobilization. The Newport Mercury printed news of the latest developments in Boston as well as the decrees of the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. Like many revolutionary newspapers during the summer of 1775, the Mercury also beat the drums of war by publishing accounts of the clashes between British soldiers and revolutionary militia throughout New England, stressing the heroism of the colonists and the barbarity of the redcoats. To help volunteers learn their new duties – and perhaps to make a profit off of the rage militaire – Southwick re-printed a British military manual explaining the latest drills, exercises, and tactics used by the royal army.

As a member of Newport’s Patriot committee of safety, Southwick likely also played a role in the mobilization of the militia and in consolidating the power of the new regime. After the Assembly staged a coup to install Nicholas Cooke at the head of Rhode Island’s revolutionary government, local committees of safety took over the government of towns and counties across the colony. Committeemen like Solomon Southwick oversaw militia enlistment, investigated potential Loyalists, and imposed taxes upon their neighbors in order to support what many still saw as an illegal rebellion. Perhaps as a reward for his unpaid service on the town committee, the revolutionary assembly appointed Southwick to the lucrative positions of postmaster and justice of the peace in 1775 and early 1776.

Common Sense; Addressed to the Inhabitants of America, by Thomas Paine, printed in Newport by Solomon Southwick, 1776. William L. Clements Library.

During the blockade of Newport Harbor and the bombardment threat, Southwick’s printing business suffered along with most others. Advertising and subscriptions dried up as merchants and townspeople pinched pennies, as did sales of books and pamphlets. Worse, Southwick was unable to get new print material from England or the Caribbean, limiting his ability to compete with printers in unblocked ports like New York City or Philadelphia. As a result, in late 1775 Southwick downsized his operations. Although he continued to publish the Mercury each week, its size was halved to a single sheet for nearly six months, and much of the rest of the printing office was shuttered.

Still, throughout the blockade Southwick continued to print the latest developments of the Continental Congress in The Newport Mercury, and in early 1776, published Rhode Island’s first edition of the sensational pamphlet Common Sense. Published in January 1776 by the English immigrant and political essayist Thomas Paine, Common Sense made a powerful argument not just for resistance to government policy but for a total repudiation of the British Empire and the establishment of an independent nation. Pointing out in plain language the flaws of the imperial system and making strong arguments for the benefits of independence and representative government, Paine’s treatise sold over 100,000 copies in its first month in print. As the war raged in New England and elsewhere, Common Sense convinced a great many colonists that independence was the only way to save their communities from ruin.

Facsimile of the first Newport printing of the Declaration of Independence by Solomon Southwick, 1776. Rhode Island State Archives.

As a supporter of Newport’s revolutionary government and a member of the town’s committee of safety, Southwick was likely intimately involved with the effort to identify and neutralize active Loyalists within the town. Along with organizing the war effort and carrying out basic municipal services, rooting out allegiance to the crown was a high priority for the new regime as it consolidated its power. Although Newport’s committee was relatively mild in its treatment of Tories, revolutionary committees throughout the United Colonies imprisoned, exiled, and confiscated the property of Loyalists and those suspected of aiding the king’s government. Still, the committee confiscated and sold off the property of Loyalists like Charles Dudley, using the proceeds to fund the Patriot military.

In July of 1776, Solomon Southwick was the first printer in Rhode Island to publish the newly-adopted Declaration of Independence. December of that year, however, found Southwick fleeing Newport on the heels of a British invasion force. Although Southwick buried his Newport press to keep it out of enemy hands, the British discovered it and used it to print a Loyalist newspaper, The Newport Gazette, during the three-year occupation. Southwick moved his family to Providence, where he served as a commissary officer in Rhode Island’s military forces and opened a new print shop. He returned to Newport after the occupation and was among the leading citizens who welcomed General George Washington to town in 1781.