This is a guest blog post by Erika Herman, a recent graduate of New York University, where she earned a master’s degree in museum studies. Erika is a 2025 Buchanan Burnham Fellow.

In 1908, the Detroit Free Press published an article about two poodles in Newport, Rhode Island. The article, “Feeds Poodles Real Ice Cream: Newport Woman Offended When Caterer Objects to Dogs Eating in His Shop—Now He Is Boycotted,” reports the experience of an unnamed woman bringing her two “beribboned poodles” into a shop and ordering each dog an expensive dish of ice cream.[1] As the dogs ate, the manger exclaimed, “‘Madam…this cannot be allowed!’”[2] As the woman and her pets exited the shop, she loudly proclaimed that she would never return.[3] The reporter concludes that “no other proper-minded Newport woman will ever again patronize such a place,” and that the proprietor “is likely to be ruined unless, indeed, he sees the error of his ways and humbly begs the poodles’ pardon.”[4]

In 1908, the Detroit Free Press published an article about two poodles in Newport, Rhode Island. The article, “Feeds Poodles Real Ice Cream: Newport Woman Offended When Caterer Objects to Dogs Eating in His Shop—Now He Is Boycotted,” reports the experience of an unnamed woman bringing her two “beribboned poodles” into a shop and ordering each dog an expensive dish of ice cream.[1] As the dogs ate, the manger exclaimed, “‘Madam…this cannot be allowed!’”[2] As the woman and her pets exited the shop, she loudly proclaimed that she would never return.[3] The reporter concludes that “no other proper-minded Newport woman will ever again patronize such a place,” and that the proprietor “is likely to be ruined unless, indeed, he sees the error of his ways and humbly begs the poodles’ pardon.”[4]

Jane Stuart, Sarah Hughes with Cat, c.1850, oil painting, gift of Catherine Hughes, Newport Historical Society Collection, 42.2.1.

While the tone of the article is a bit mocking of the Newport woman and her pets, it is clear that these dogs were beloved. Perhaps some of us even see similarities to how we treat our pets today. Stories of wealthy nineteenth and early twentieth century Newporters and their pets often made their way into the society pages, illuminating the luxury of the elite lifestyle for the rest of the public. However, pets were not just the companions of high society—even before the poodles in ribbons eating ice cream, pet birthday parties, and $10,000 pet mausoleums of the Gilded Age, pets could be found in Newport homes.

Carte-de-visite of Morley Harison with dog, c. 1863, A. Terris, Newport Historical Society Collection, P8118.

The history of pet keeping in America illuminates many themes including the importation of European customs and thought, the impact of class identity and wealth, ideas about American identity, and the changing relationships between humans and animals. By the time early colonists first arrived, Indigenous people already had relationships with the animals of the land.[5] Dogs were the most common because they guarded homes, pulled sleds, helped during a hunt, and provided companionship.[6] Europeans brought their own dogs and cats with them—dogs to guard, hunt, and provide companionship and cats mainly to hunt mice and other vermin.[7] Local animals were also domesticated; birds, deer, and squirrels became quite popular as pets.[8] Through the early nineteenth century, the category of “pet” was nebulous—dogs worked as guard dogs or hunters but could also provide companionship, cats were mainly seen as mouse-catchers but eventually made their way into the home, caged songbirds graced kitchens and parlors, baby squirrels were a popular pet for young boys to capture and raise, and deer in ribbons provided entertainment at parties.[9] Having a pet was an important part of childhood, as keeping an animal was seen as a way for children to learn responsibility and kindness.[10] Beloved pets were sometimes included in portraits, showing the importance of the animal to their human. In the collections of the Newport Historical Society there are a few examples of pre-photograph depictions of pets. In 1772, Mary Tillinghast stitched a sampler in which two dogs play outdoors, one jumping onto a woman’s lap.[11] In the mid-19th century, Jane Stuart painted Sarah Hughes with her cat cradled in her arms wearing a bow to match her dress.[12] There is also a painting of Clarica G. Simons (later Mrs. Clarica Gardiner Simons Allen) as a child holding her poodle by a blue ribbon.[13] Looking at these early depictions of pets, one can see the care people had for their pets.

Tintype photograph of unidentified member of the King family with a whippet dog, c. 1870, Newport Historical Society Collection, FIC.2022.126.

The nineteenth century brought changes to the ideas on and practices of pet keeping. The rise of the middle class brought pets into more households as companions and as social status indicators.[14] As photography became more accessible in the 1840s, the number of pet portraits—with and without their humans—steadily rose in numbers.[15] People brought their pets to the studio with them, wanting to capture those who meant the most to them as a keepsake. It was around this same time that pet training manuals increased in popularity and used language of “‘educating’ or ‘civilizing’ the animal.”[16] This idea of “civilizing” was central to white American politics and culture in the nineteenth century and led to many damaging policies and ideologies. These included belief in Manifest Destiny, suppression of Indigenous cultures and languages, and promotion of assimilation for new immigrants. Not even pets were left out of this drive to civilize.

Giovanni Boldini, Portrait of Elizabeth Drexel Lehr, 1905, oil on canvas, 86 x 46 in, bequest of Mrs. Eva Drexel Dahlgren, The Elms, The Preservation Society of Newport County, https://newportalri.org/items/show/6908.

Nineteenth century ideas of domesticity, gender roles, and good citizenship also impacted pet keeping. Cats were thought to enjoy the home and therefore became associated with women, the traditional keeper of the house.[17] Dogs were thought of as a more masculine pet as they would go out hunting or undertake other jobs outside the home.[18] Ideas about the treatment of animals began to change into one of a “domestic ethic of kindness to animals” which “was one product of a constellation of ideas and cultural ideals, including gentility, liberal evangelical Protestant religion, and domesticity.”[19] By the end of the nineteenth century, this “domestic ethic of kindness” had led to the creation of various animal rights organizations.[20] In 1866, Henry Bergh found the American Society For the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) in New York City to eliminate abuse of working animals (dogs and horses) and livestock.[21] The Rhode Island chapter opened in 1870.[22] In Newport specifically, Virginia Potter, Mary van Beuren and Emma Norman founded The Newport County League for Animals (renamed The Potter League in 1958) in 1929 to care for abused and abandoned animals.[23] The organization’s first shelter opened in 1931 on Harrington Street in Newport, and in 1978 they moved to Middletown after outgrowing their original space.[24]

Photographic print of Mrs. Norman de Rham Whitehouse and dog at Bailey’s Beach, c. 1925, Townend Studios, gift of Martin Murphy, Newport Historical Society Collection, P8432.

Billy Young, manager of Baily’s beach, removing Mrs. Norman de Rham Whitehouse’s dog from the beach due to a “no dogs allowed” rule. Newport Historical Society Collection, P8442.

Now we come back to the wealthy Newporters of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as it was stories of their pets that featured in the papers. One such story is that of the 1901 “Dog’s Dinner” hosted by Henry (Harry) Symes Lehr and Elizabeth Wharton Drexel at their home Arleigh. Drexel mentions the event in her 1935 tell-all book “King Lehr” and the Gilded Age. Bored with another season of the same social gatherings, the couple invited the dogs of high society (and their owners) to a dinner of “stewed liver and rice, fricassee of bones and shredded dog biscuit” on their veranda.[25] An enterprising reporter snuck into the event with a dog as a disguise, but was eventually discovered and thrown out of the party, resulting in “scathing columns [that] appeared in the newspapers next day.”[26] One headline read, “Nearly A ‘Frost.’ Harry Lehr’s Dog Party Not a Big Hit.”[27] The story was spread so widely that the Philadelphia Inquirer reported that a Pennsylvania minister, Rev. H. B. Musselman, denounced the Newport dog dinner saying, “such degeneracy…has only been equaled in history by the carrying on of the most depraved people in the time of Nero.”[28] Clearly the display of extravagance put on for the dogs both entertained and disgusted people around the country, but no one could look away. The poor reactions of others did not dissuade Harry Lehr from hosting more dog dinners and parties, with newspaper articles in 1902 and 1903 mentioning similar gatherings and one article in 1904 describing the third birthday party of Drexel’s Pomeranian “Mighty Atom.”[29] Written in a much lighter tone, the article calls the event “one of the season’s great successes.”[30] Red dahlias (because “Mighty Atom” liked the color red) and silver candelabras decorated the table and five butlers served the meal of veal cutlets, Frankfurters, salads, ice cream, and chocolates.[31] The night ended with a birthday cake with three candles.[32] However, not everyone thought the party a triumph, with one critic titling their article “Dogs Not to Be Blamed,” and concluding “at the end of a chain a dog goes many places that he would prefer not to.”[33]

Photographic print of John Driscoll, Mary Emerson, George Emerson, and Mary Emerson with dog, c. 1972, gift of Nan Gartenberg, Newport Historical Society Collection, 2018.047.005.

Dogs were a favored pet of the wealthy, though of course there were also the more exotic pets. Oliver H. P. Belmont and W. K. Vanderbilt purchased six miniature bulls and cows in 1894 which were eventually pastured in Gray Crag Park, and Harry Lehr and other society ladies brought monkeys to various dinner parties.[34] The wealthy were also able to treat their pets to luxuries unattainable to most people. When Miss Pauline Le Roy French’s dog broke its leg in Newport in 1908, Miss French brought her pet to a veterinary surgeon in New York where the dog received leg splints.[35] This was unusual, as most badly injured pets were euthanized since small-animal veterinarians were relatively rare until the 1930s.[36] This was a novel enough action that it ended up in the society pages of the New York Times. When a beloved pet did die, those belonging to the ranks of New York Society may have found their final resting place at the pet cemetery tucked away in Westchester County. Started by a New York City veterinarian who served a wealthy clientele, the cemetery held graves for dogs, cats, monkeys, and even a lion.[37] Mrs. M. F. Walsh, of New York and Newport, erected a $10,000 mausoleum for her bulldog “Toodles.”[38]

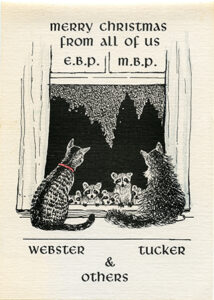

In the later twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the love Newporters had for their pets remained. The NHS collection shows that people continued to heavily document their pets’ lives through photographs—pets at home, pets at the beach, pets in the snow, pets at parties. Pets became seen as family members, and there are many Christmas cards in the collection featuring people’s pets. One card is even addressed to the dog instead of their human. Today, Newport remains a pet friendly place. The number of dogs (and at least one cat in a stroller) out about town proves this to be true.

To see other pets in the collections of the Newport Historical Society, click here!

Christmas card with image of two cats staring out the window at a family of raccoons. From “All of Us, E.B.P, M.B.P, Webster, Tucker & Others”

[1] “Feeds Poodles Real Ice Cream: Newport Woman Offended When Caterer Objects to Dogs Eating in His Shop—Now He Is Boycotted,” Detroit Free Press, June 21, 1908, A9, http://proxy.library.nyu.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistorical-newspapers%2Ffeeds-poodles-real-ice-cream%2Fdocview%2F564128707%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D12768.

[2] “Feeds Poodles Real Ice Cream,” Detroit Free Press.

[3] “Feeds Poodles Real Ice Cream,” Detroit Free Press.

[4] “Feeds Poodles Real Ice Cream,” Detroit Free Press.

[5] Katherine C. Grier, Pets in America: A History (The University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 11.

[6] Joshua J. Mark, “Pets in Colonial America,” World History Encyclopedia, April 19, 2021, https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1728/pets-in-colonial-america/.

[7] Mark, “Pets in Colonial America.”

[8] Mark, “Pets in Colonial America.”

[9] Grier, Pets in America, 20.

[10] Grier, Pets in America, 11.

[11] Sampler by Mary Tillinghast, Newport Historical Society Collection, 01.202.

[12] Sarah Hughes with Cat, oil painting by Jane Stuart, Newport Historical Society Collection, 42.2.1.

[13] Clarica G. Simons, oil painting, Newport Historical Society Collection, 26.1.4.

[14] “For the Love of Animals: Pet Keeping and Animal Activism,” The Preservation Society of Newport County, “Wild Imagination: Art and Animals in the Gilded Age,” accessed July 24, 2025, https://www.newportmansions.org/events/wild-imagination/.

[15] Grier, Pets in America, 57.

[16] Grier, Pets in America, 73.

[17] “Cats & Dogs: Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century Perspectives,” Biodiversity Heritage Library, accessed July 26, 2025, https://blog.biodiversitylibrary.org/2017/07/cats-dogs-nineteenth-and-early-twentieth-century-perspectives.html.

[18] “Cats & Dogs: Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century Perspectives,” Biodiversity Heritage Library.

[19] Grier, Pets in America, 12.

[20] “For the Love of Animals: Pet Keeping and Animal Activism,” The Preservation Society of Newport County.

[21] “For the Love of Animals: Pet Keeping and Animal Activism,” The Preservation Society of Newport County.

[22] “For the Love of Animals: Pet Keeping and Animal Activism,” The Preservation Society of Newport County.

[23] “History,” Potter League, accessed July 24, 2025, https://potterleague.org/about/history/.

[24] “History,” Potter League.

[25] Elizabeth Drexel Lehr, “King Lehr” and the Gilded Age (Papamoa Press, 2017, original text 1935), 167.

[26] Lehr, “King Lehr” and the Gilded Age, 167.

[27] “Nearly a ‘Frost.’ Harry Lehr’s Dog Party Not a Big Hit,” Boston Daily Globe, August 30, 1901, 6, http://proxy.library.nyu.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistorical-newspapers%2Fnearly-frost%2Fdocview%2F499513137%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D12768.

[28] “Minister Denounces Recent Party Given to Pet Dogs,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 23, 1901, 4, http://proxy.library.nyu.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistorical-newspapers%2Fseptember-23-1901-page-4-16%2Fdocview%2F1827066029%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D12768.

[29] “The Coming Event at Newport,” The Washington Post, August 10, 1902, 18, http://proxy.library.nyu.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fnewspapers%2Fcoming-event-at-newport%2Fdocview%2F144369839%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D12768; “Same Old Newport Clown,” Washington Post, June 26, 1903, 6, http://proxy.library.nyu.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fnewspapers%2Fsame-old-newport-clown%2Fdocview%2F144409169%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D12768; and “Dogs Dine with 400: Harry Lehr Is Director of Canine Birthday Party, Mighty Atom is the Host. Seven Aristocratic Pets Are Entertained at Ardleigh. Cats Alone Did Not Like It. Formal Invitations Sent. Menu Is Elaborate. Not Fond of Cigarets.” Chicago Tribune, October 1, 1904, 1, http://proxy.library.nyu.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistorical-newspapers%2Fdogs-dine-with-400%2Fdocview%2F173192643%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D12768.

[30] “Dogs Dine with 400,” Chicago Tribune, 1.

[31] “Dogs Dine with 400,” Chicago Tribune, 1.

[32] “Dogs Dine with 400,” Chicago Tribune, 1.

[33] “Dogs Not to Be Blamed,” Washington Post, October 16, 1904, E6, http://proxy.library.nyu.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fnewspapers%2Fdogs-not-be-blamed%2Fdocview%2F144515194%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D12768.

[34] “Mr. Belmont’s Queer Collection: Newport People Expert Soon to See Him Driving a New Turnout,” New York Times, July 30, 1894, 5, http://proxy.library.nyu.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistorical-newspapers%2Fmr-belmonts-queer-collection%2Fdocview%2F95184012%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D12768; “Monkeys on Wires Are Rage Among Smart Set: Fuzzy Little Dwarf Pets Are Introduced at Sherry’s by the Elite,” The Indianapolis Morning Star, August 26, 1904, 6, http://proxy.library.nyu.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistorical-newspapers%2Fmonkeys-on-wires-are-rage-among-smart-set%2Fdocview%2F756391439%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D12768;

[35] “Surgeon for Newport Dog: Miss French’s Pet’s Broken Leg Is Being Set In New York,” The New York Times, April 24, 1908, 1, http://proxy.library.nyu.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistorical-newspapers%2Fsurgeon-newport-dog%2Fdocview%2F96811902%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D12768.

[36] Grier, Pets in America, 12.

[37] “Where Society Prays and Weeps on the Graves of Dogs: Very Remarkable Photographs Caught Where Women Sob Over Marble Mausoleums and Granite Headstones of Departed Pets,” Indianapolis Star, July 2, 1922, SM2, http://proxy.library.nyu.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fhistorical-newspapers%2Fwhere-society-prays-weeps-on-graves-dogs%2Fdocview%2F741425792%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D12768.

[38] “Where Society Prays and Weeps on the Graves of Dogs,” Indianapolis Star, SM2.