This is a guest blog post by Emily DeFazio, BA in History, minor in Italian and Digital Marketing, Notre Dame. Emily is a 2024 Buchanan Burnham Fellow.

Visitors to Newport’s idyllic harbor front may be surprised to learn that the largest mass execution in the colonies occurred at a site just off the end of Long Wharf. On July 19, 1723, twenty-six pirates were hanged at Gravelly Point.[1] Captain Charles Harris (1698-1723) of the Ranger had been captured with his crew off the shores of Block Island following a plundering spree along the Eastern Seaboard by Harris and his associate, Ned Low (1690-1724). The Ranger crew was transferred to Newport, where they awaited their trial following the escape of Low’s ship, the Fortune.[2] The entire city turned out that July afternoon—not to mention those who had traveled to Newport for the event—to witness the aftermath, which author Katherine Howe describes as a “great public spectacle” meant to discourage others from following in the pirates’ footsteps.[3]

View from the top of Washington Square, looking towards Long Wharf. The piracy trial was held in an older wooden courthouse (on the site of the present-day Colony House), while the pirates were ultimately hanged near the end of Long Wharf on July 19, 1723. P9223, collection of the Newport Historical Society.

While a dramatic signal that piracy in Newport would no longer be tolerated, Gravelly Point was a spectacle that would have been unimaginable half a century prior. During the mid-seventeenth century, privateering—legally sanctioned piracy meant to aid the navy in times of war—had been utilized by the British government in excess.[4] Even the most respected families in Newport participated; for example, William and John Wanton, both of whom went on to be Governors of Rhode Island, served as privateers, which they leveraged to increase their power and status in the colony.[5] Perhaps unsurprisingly, the rise in privateering conversely caused a rise in piracy, with some privateers slipping into illegal exploits to claim a larger share of the wealth that was at stake. These pirates soon flooded Newport’s economy with foreign coin, which became common currency throughout the town.[6]

Therefore, piracy seemed to be implicitly accepted in Newport, the riches gained from plundering being too appealing to resist in a city with a dominant merchant class. An unexpected but effective lens to examine this through is the interaction between pirates and members of Newport’s Quaker congregation. By the late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-centuries, Quakerism had emerged as the dominant religious body in Newport, with one-half of the island practicing the religion by 1700.[7] Many prominent members of the Quaker community also held powerful governmental positions; several colonial Governors of Rhode Island were part of Newport’s congregation. Despite being intensely averse to violence, many Quakers were merchants by trade, putting them in a position to do business with pirates looking to invest their plunder in the town. Because of this, those same Governors protected pirates on multiple occasions.

Captain Thomas Paine (1632-1715) was among the first pirates to engage with Newport and its Quaker leadership. When Paine arrived in Newport in 1683 as a pirate known to have raided the Floridian coast, Quaker Governor William Coddington, Jr. (1651-1689) accepted his privateering commission as valid even though the Governors of New York and New Hampshire claimed it was a forgery. Historians have speculated that Paine also contributed a cash bribe to the situation, which would have appealed to the merchant-minded Quaker Governor.[8] While some accused Coddington of sheltering a known pirate, Paine settled in Newport and bought property—undoubtedly using ill-gotten funds in the purchase.[9] Any local dissent dissipated in the subsequent decade and Paine soon became a leading citizen; he is listed as one of the founding members of Newport’s Trinity Church and was called to defend the city in 1690 from French privateers.[10] His status was further elevated by his marriage to Mercy Carr, daughter of prominent Quaker Caleb Carr, which connected him to the ever-growing Quaker community. This union served as a useful security blanket when Paine came under scrutiny for assisting Sarah Kidd, wife of the notorious Captain William Kidd (c. 1654-1701), as she appealed her husband’s imprisonment in Boston.[11] Paine’s assimilation into Newport would not have been possible without a Quaker Governor’s intervention and decision to disregard the accusations of piracy against him.

Engraving of infamous pirate Thomas Tew. Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. V.89 NO.534, P.812, 1894.

Thomas Tew (d. 1695) was another known pirate who enjoyed a positive relationship with local Quakers. When Tew—a descendant of Richard Tew (1605-1673), one of the original settlers of Newport—returned to the city in April, 1694 following a successful run at piracy, he was welcomed with open arms that were grasping for a piece of his reported £100,000 haul.[12] According to John Graves, an associate of Tew in Newport, the pirate was free with information that “he was last year in the Red Sea, that he had taken a rich ship belonging to the Mogul.”[13] Governor Caleb Carr (1616-1695, Quaker father-in-law to Captain Thomas Paine) was among those willing to look the other way as the pirate settled in the town, for he also accepted “a generous present” of his own from Tew.[14] Tew lived in Newport until 1694, the year before his death, when he returned to life on the high seas.[15] As was the case with Paine, it appears Governor Carr’s interests in the economic advantages of engaging with a wealthy pirate outweighed his religious beliefs, allowing yet another pirate to embed themselves in Newport’s community.

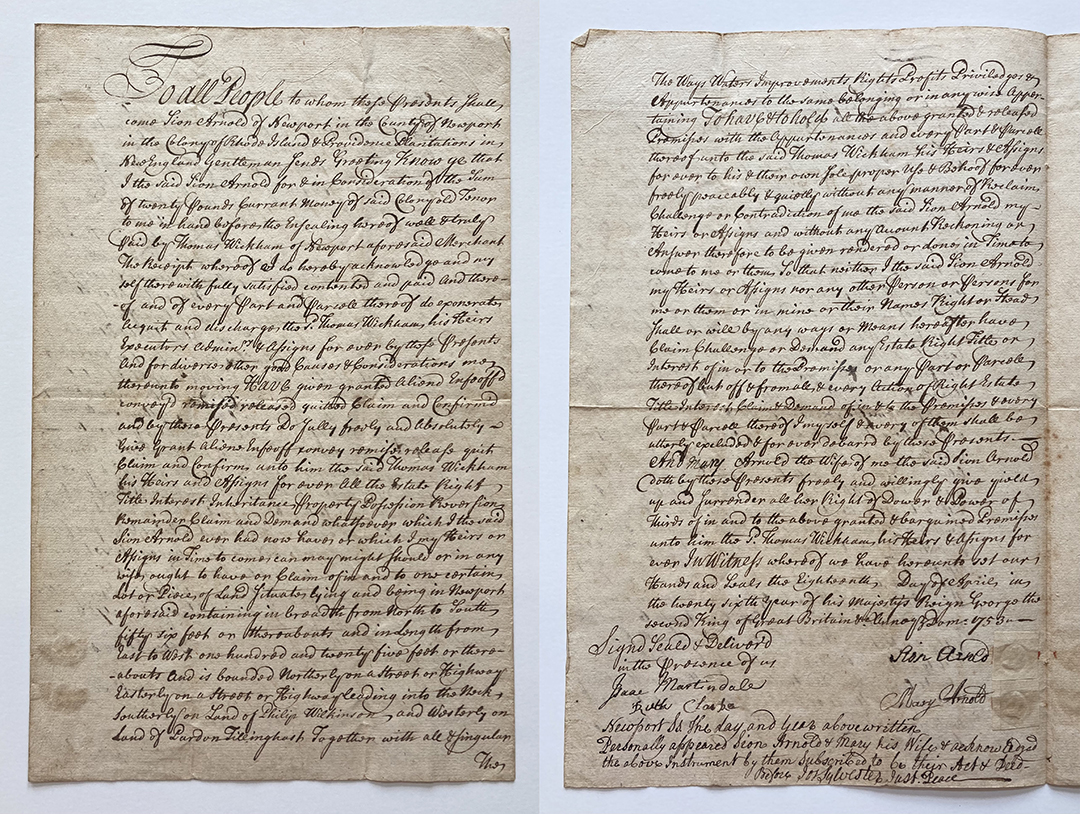

A later example is Sion Arnold (1674-1753), a member of Newport’s prominent Arnold family. After being arrested for piracy in 1699 and subsequently released, Arnold married Newporter Mary Ward (1679-1754), sister to the future Governor Richard Ward (1689-1763). Arnold also economically invested in Newport through property ownership. In a deed dated April 18, 1753, Sion had “personally appeared…before Sylvester Just. Peace” to sign for a sale of land.[16] William Coddington, Jr. (1710-1780) also signed off on the document, another trace of Quakers who, despite their religious views, did not proactively prevent known pirates from laying down roots in the town.

While Newport was turning a blind eye to piracy, the British government was simultaneously cracking down on the practice. Richard Coote, Earl of Bellomont (1636-1700) replaced pirate-sympathizer Governor Benjamin Fletcher (1640-1703) as Governor of New York in 1698 and immediately began taking action against pirates.[17] Lord Bellomont had a hand in pursuing each of the aforementioned pirates that had ties to Newport. Bellomont awarded Captain Kidd a privateering commission in 1695 with the aim of curtailing piracy; Thomas Tew was one of the top targets.[18] Following Kidd’s perceived transition to piracy, Bellomont ordered Thomas Paine’s Jamestown property to be searched for implicating evidence.[19] Finally, when Sion Arnold was released in 1699, Bellomont personally complained to the board of trade about the outcome.[20]

A deed of sale for land sold by Sion Arnold to Thomas Wickham on April 18, 1753. Sion presented himself in person to sign the document in Newport. Quaker William Coddington, Jr., town clerk at the time, also signed it. 2019.021.013, collection of the Newport Historical Society.

With British authorities hitting increasingly closer to home, leaving a trail of severe consequences for pirate sympathizers in their wake, Newporters in positions of power could no longer be so blatant in their associations with pirates, lest they end up like the disgraced Governor Fletcher (who frequently hosted Tew for dinner at his New York headquarters).[21] The line against pirates in Newport was drawn in 1723; the spectacle at Gravelly Point served to mask any pervious piratical connections by broadcasting the message that piracy would not be tolerated in the town.

In a record of the trial and execution, one of the condemned, John Browne, lamented that his “’Sins, by the Justice and Will of God brought [him] to fall into the Hands of Pirates.’”[22] It serves as a poetic final word to the long history of piracy in Newport—one ironically reinforced by the religious Quakers, who forged business partnerships and family ties with several notorious pirates. This brutal spectacle at Gravelly Point sought to utilize dramatics to mask these deliberate ways in which Newporters had allowed piracy to permeate the city.

Banner: “Captain Kidd in New York Harbor” by artist Jean Leon Gerome Ferris, ca. 1932. Cleveland, Ohio: The Foundation Press, Inc., July 28. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2002719524/.

[1] Gloria Merchant, Pirates of Colonial Newport (Charleston: The History Press, 2014), 85.

[2] Eric Jay Dolan, Black Flags, Blue Waters (New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2018), 289.

[3] Katherine Howe addressed this during her April 30, 2024 book launch event at the Newport Colony House. It was in conversation with Dr. Daphne Geanacopoulos.

[4] Merchant, Pirates of Colonial Newport, 18.

[5] As cited in the NHS Rogues and Scoundrels Walking Tour.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Elaine Robinson, “Orin Bullock and the Restoration of the Great Friends Meeting House,” Newport

History: Vol. 82: Iss. 268 (2013), Article 2.

[8] Merchant, Pirates of Colonial Newport, 35.

[9] Dolan, Black Flags, Blue Waters, 34.

[10] Ibid, 39; Merchant, Pirates of Colonial Newport, 38.

[11] Merchant, Pirates of Colonial Newport, 38.

[12] Dolan, Black Flags, Blue Waters, 53.

In a 2008 Forbes article entitled “Top Earning Pirates,” Tew’s wealth was estimated at $103 million, the third highest in pirate history. https://www.forbes.com/2008/09/18/top-earning-pirates-biz-logistics-cx_mw_0919piracy.html

[13] “America and West Indies: February 1697, 16-20,” in Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 15, 1696-1697, (London, 1904) 367-379. British History Online, accessed June 27, 2024, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol15/pp367-379.

[14] Dolan, Black Flags, Blue Waters, 53.

[15] As cited in the NHS Rogues and Scoundrels Tour.

[16] Sion Arnold to Thomas Wickham, 18 April 1753, 2019.021.013, NHS Manuscript Collections. https://collections.newporthistory.org/Detail/objects/14465

[17] Daphne Geanacopoulos, The Pirate’s Wife: The Remarkable True Story of Sarah Kidd (Ontario: Hanover Square Press, 2022), 72.

[18] Ibid, 75.

[19] Merchant, Pirates of Colonial Newport, 38.

[20] Ibid, 55

[21] Geanacopoulos, The Pirate’s Wife, 74.

[22] “Useful remarks. An essay upon remarkables in the way of wicked men: A sermon on the tragical end, unto which the way of twenty-six pirates brought them; at New Port on Rhode-Island, July 19, 1723. : With an account of their speeches, letters, & actions, before their execution. : [Two lines from Deuteronomy].” In the digital collection Evans Early American Imprint Collection. University of Michigan Library Digital Collections. Accessed June 27, 2024. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=evans;cc=evans;rgn=main;view=text;idno=N02066.0001.001