This is a guest blog post by Jenny Sullivan, MA in History, University of Rhode Island. Jenny is a 2024 Buchanan Burnham Fellow.

While Newport is widely known today for its connections to and promotion of the performing arts, the mere existence of such performances was at one time actively resisted by citizens and legislators alike. Newport County is the birthplace of many cultural institutions, such as the Newport Jazz & Folk Festivals, and has served as the backdrop for countless films and television shows throughout the 20th & 21st centuries. However, Newport’s history with the performing arts began centuries before the age of the silver screen, serving as host to New England’s first “temple of the muses,” or, theater.*1 The city was not spared when anti-theatre laws spread throughout the colonies in the 18th century, but the existence of theatre in Newport both before and after its prohibition demonstrates the city’s resilient magnetism to the performing arts.

By the 1750s, theatrical performances were not entirely unheard of in the colonies, although their acceptance was generally limited to southern colonies like Virginia and the Carolinas.2 Pervasive Quaker and Puritan ideologies in the northern colonies deterred most aspiring performers from attempting to take the stage, with several anti-theatre laws already in place by the mid-1700s. Theatre was inextricably associated with sins such as drinking and gambling and was often preemptively banned in northern colonies even when no performances were being rehearsed or playhouses constructed to host such spectacles.3 New England’s reputation as a region of religious rigidity certainly played a major role in antagonism toward theatre in the colonial period, but it was not the only contributor. Ongoing friction due to British interference in colonial governments was exemplified by the British’s power to repeal colonial laws as they saw fit, and the anti-theatre laws passed by the colonists were frequently overturned so the British might stage their own productions. As Rhode Island was not governed by a British appointed governor, it exerted a bit more control over the legislation it passed than other colonies. However, simmering antipathies toward British sympathizers and loyalists within the colony of Newport contributed greatly, if not more than religious ideologies, to the prohibition of theatre in Rhode Island. At the time, theatre was considered a thoroughly British art form since most, if not all, of the plays being performed were written by British playwrights and popular on the London stage. Therefore, participation of any kind in theatrical performances was often linked to support of the monarchy as well as a lack of morality.4

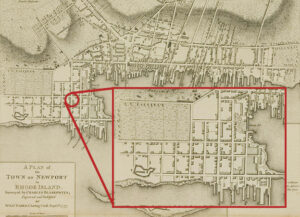

Charles Blaskowitz’s 1771 map of Newport colony. The playhouse near Dyer’s Gate was situated within the empty rectangular plot of land. 01.952, collection of the Newport Historical Society.

Nevertheless, the colony of Newport “…had been settled in a spirit of religious and social liberty which was stranger to the neighboring commonwealths,” and was seen as the only potential New England location in which a theater might thrive.5 The Douglass-Hallam Company, who first performed in Williamsburg, VA, in 1752, made plans to go north to Newport.6 They had acquired a recommendation from the governor of Virginia for both the quality of their performances and the quality of their characters with the hope that this might be enough to assuage any lingering apprehension about the endeavor.7 Ahead of their arrival, a vote was taken at the August 1, 1761, Town Council meeting declaring that plays were not allowed to be performed in Newport. Ten days later, Newport Mercury published an article that not only advertised the upcoming performances but also printed the governor of Virginia’s recommendation right below it.8 Whether that character reference was enough to mollify the dissenters of theatre in Newport is unknown. Nevertheless, the Douglass-Hallam Company, opened their playhouse doors on September 7, 1761, with a production of Cibber-Vanbrugh’s The Provok’d Husband.9

There is no official record or illustration of the building first used by the Douglass-Hallam Company, also known as the London Company, in Newport, only that it was “a slight temporary building, and stood on a lot in the North part of that part of town called Easton’s Point, near Dyer’s Gate.”10 This first playhouse’s location is contemporarily accepted as being near present-day Third and Cherry Streets.11

It was likely a crude building with none of the elements considered standard for theaters today – namely, seating and a floor.12 The London Company performed in Newport until November and were obviously met with considerable success as they returned to town the next summer. When the London Company returned in 1762, the playhouse in Easton’s Point no longer existed— either torn down, destroyed, or otherwise occupied. Instead, they took up residence in the King’s Arms Tavern. As this tavern was later destroyed in the American Revolution and there is no surviving information about its interior, one can only assume it was probably a smaller venue than the 1761 playhouse but larger than the other taverns in town to accommodate spectators.13 A playbill dated June 10, 1762, indicates that Shakespeare’s Othello was the 1762 season opener, though Douglass & Hallam chose to advertise the show as a ”moral dialogue” about the disastrous effects of jealousy in an attempt to present theatre as a tool for promoting morality, indicating the presence and prevalence of anti-theatre supporters in town.14

1818 painting of Washington Sqaure and the Brick Market by an unidentified Hessian artist when the Old Theater was operating within. 94.4.1, collection of the Newport Historical Society.

The London Company left for Providence in August, only to find another town vote had prohibited theatrical performances. While they initially attempted to perform regardless, as they did successfully the summer previous in Newport, the General Assembly of Rhode Island passed severe anti-theatre legislation, halting all performances for decades to come.15 If there was any surviving hope for the resurrection of theatre during this time, it was completely shattered by Congress’s passage of the Article of Association in 1774, in which Article 8 specifically promoted frugality and denounced frivolous entertainments, such as gambling, horse-racing, and theatrical performances. In 1778, Congress passed stricter legislation that barred anyone holding a public office from performing in, encouraging, or attending theatrical performances at the risk of losing their job.16 The stakes were certainly high enough to deter the pursuit of performance. Compounded by the nation’s newly won independence and occupation with establishing a sovereign country, it took almost a decade after peace for anti-theatre legislation to be overturned in Rhode Island.17

Performances began again in Providence in late 1792, and in February of 1793, the General Assembly repealed Rhode Island’s anti-theatre legislation.18 By May, it was reported that Alexander Placide, a French acrobat and tightrope dancer, and Joseph Harper, a member of the London Company – now called the American Company – were granted permission to renovate the Brick Market into a theater for the public.19

“Mr. Garrick in the Character of Richard III” by William Hogarth, June 20, 1746. Garrick was a prolific British actor and playwright, and his plays were performed on the Newport stages. 32.35(238), collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Brick Market Theater, referred to as the Old Theater, opened on Monday, June 24, 1793, with a performance of The Tragedy of Jane Shore.20 That same week Harper & Placide’s troupe performed tightrope dancing, a comedy by Joseph Addison titled The Drummer, and a pantomime written by Placide himself, The Old Soldier.21 The variety of spectacles offered at The Old Theater was indeed vast, with performances running 2-3 nights a week. Large-scale reenactments of The Battle of Bunker Hill—where a squad from the Newport Guards would don red coats and play British soldiers while local men likely played the roles of the militia—were particularly popular.22 The interior of The Old Theater was quite simple, adorned with a simple green curtain upon which the words “To hold the mirror up to nature” were placed. There was gallery, pit, and box seating that allowed The Old Theater to seat about 250 people per performance.23

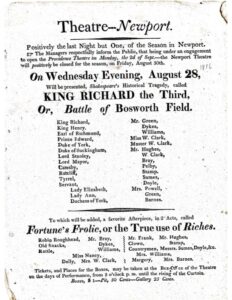

Advertisement for a performance of Richard III at the Old Theater in Brick Market. Several of Shakespeare’s plays were performed for the first time in New England at the Old Theater. Ms.133 BRO-2, collection of the Newport Historical Society.

Joseph Harper, along with Charles Stuart Powell, another prominent figure in early American theatre, continued to manage, use, and rent out The Old Theater into the early 1800s. The Old Theater was utilized by various groups for various performances, lectures, and meetings until 1842 when it was renovated into Newport’s City Hall, referred to as Old City Hall today.24

The early 19th century also saw some local Newport actors open the doors to two rival theaters – one called “Fly Market Theatre” that opened on the north side of Bannister’s Wharf, and another called “Drury Lane Theatre” on the north side of Mill Street.25 Little is known about the interiors of these theaters or what plays were performed there. In the decades and centuries since, a multitude of performance venues, both temporary and permanent, have entertained hundreds of thousands of spectators with a variety of artistic offerings.

It is difficult to think of Newport as a place where artistic expression and performance was not celebrated as it is today, but like so many aspects of Newport’s history, understanding the past greatly enriches the present and informs the future for generations to come.

“Theatre, Newport” engraved and printed by Fenner Sears & Co., published by I.T. Hinton & Simpkin & Marshall, December 15, 1831. Newport vertical file, RLC.Ms.035, Redwood Library and Athenaeum.

*(Note on Terminology: theater v. theatre – Both spellings are correct, however “theater” is considered the American English spelling, while “theatre” is the British English spelling, and is more commonly used. Some also make the differentiation between “theater” being used as a noun describing the physical building plays are performed in, and “theatre” as the noun to denote the art form that is theatrical performance. As both spellings of the word and its dual meanings are heavily utilized in this research, I will be using both spellings with “theater” as representative of place, and “theatre” as representative of the art form.)

Banner photo: “The Prospect Before Us, Respectfully dedicated to those Singers, Dancers, & Musical Professors, who are fortunately engaged with the Proprietor of the Kings Theatre, at the Pantheon” by Thomas Rowlandson, January 13, 1791. 59.533.421, collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

[1] George Owen Willard, History of the Providence Stage, 1762-1891 (Providence: The Rhode Island News Company, 1891), 5.

[2] B.W. Brown, “The Colonial Theater in New England,” Newport Historical Society Journals 76 (July 1930): 4.

[3] Meredith Barton, “’The Tenter-Hooks of Temptation’: The Debate Over Theatre in Post-Revolutionary America,” The Gettysburg Historical Journal 2 (2003): 81.

[4] Barton, “’The Tenter-Hooks of Temptation,’” 81-84.

[5] Brown, “The Colonial Theater in New England,” 7.

[6] Williamsburg Virginia Gazette, August 21, 1752; Willard, History of the Providence Stage, 3.

[7] Newport Daily News, February 23, 1878; Brown, “The Colonial Theater in New England,” 7-9.

[8] Town Meeting Records, August 1761; Willard, History of the Providence Stage, 5-6.

[9] Brown, “The Colonial Theater in New England,” 10; Donald C. Mullin, “Early Theatres in Rhode Island,” Theatre Survey 11, no. 2 (November 1970): 170.

[10] Henry Bull, Memoir of Rhode Island, 45-46.

[11] Brown, “The Colonial Theater in New England,” 9; Mullin, “Early Theatres in Rhode Island,” 168-170.

[12] Mullin, “Early Theatres in Rhode Island,” 170-171; Willard, History of the Providence Stage, 6.

[13] Mullin, “Early Theatres in Rhode Island,” 171-172.

[14] Brown, “The Colonial Theater in New England,” 13-15; Willard, History of the Providence Stage, 7-10; Mullin, “Early Theatres in Rhode Island,” 171-172.

[15] Although the act itself was closely modeled after Massachusetts’s anti-theatre legislation, the penalties were much harsher financially. Even spectators could be penalized for attending shows and were instead incentivized to report performers to the authorities with the promise of half the exorbitant penalty fees if the performers were convicted.

Brown, “The Colonial Theater in New England,” 18-22; Willard, History of the Providence Stage, 13-15.

[16] Brown, “The Colonial Theater in New England,” 24-25; Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/05000059/.

[17] The pattern of post-Revolutionary War reversals of anti-theatre laws can likewise be linked to colonial antagonism toward the British. The more hostility a city or state harbored for the British, the longer it took to repeal the anti-theatre laws because the laws’ very existence was a symbol of independence from Britain.

Barton, “’The Tenter-Hooks of Temptation’,” 87-90.

[18] Willard, History of the Providence Stage, 23; Mullin, “Early Theatres in Rhode Island,” 176.

[19] Newport Mercury, June 4, 1793.

The London Company changed their name to the American Company, or the Old American Company, following the negative aftermath of the Stamp Act of 1765.

David Malinsky, “Congress Bans Theatre!” Journal of the American Revolution, last modified December 12, 2013, https://allthingsliberty.com/2013/12/congress-bans-theatre/.

[20] Mullin, “Early Theatres in Rhode Island,” 176-177.

[21] Newport Mercury, June 25, 1793; Richard Phillip Sodders, “The Theatre Management of Alexandre Placide in Charleston, 1794-1812. (Volumes I & II) (South Carolina),“ (PhD dissertation, Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College, 1983), 45-46.

[22] Howland, ”Reminiscences of Old Newport, no. 3,” Newport Mercury, November 8, 1873.

[23] Newport Mercury, May 2, 1885; Newport Mercury, May 16, 1885.

[24] Willard, History of the Providence Stage, 23-24; Newport Mercury, May 16, 1885.