This guest post was written by Henry Snow, PhD Candidate, History, Rutgers University, whose recent research at the NHS was supported by the New England Regional Fellowship Consortium. Henry’s research topic is ‘The Ends of the Ocean: Power and Change at the Atlantic Dockside, 1740-1840’.

Rhode Island was an epicenter of revolution in more ways than one. The Gaspee Affair, and Rhode Islanders’ influential role in the Stamp Act crisis, is well known. A great deal of revolutionary fervor in Rhode Island was driven by the colony’s relationship to maritime trade. From below, rioting mariners attacked press gangs; from above, wealthy merchants plotted against the state. A 1772-3 smuggling case recorded in a remarkably detailed 82-page document in the NHS holdings provides a unique window into the mindset and machinations of the latter category of revolutionary (1774 Summary of Nathaniel Shaw vs. Charles Dudley, Newport Historical Society, Box 60, Folder 4).

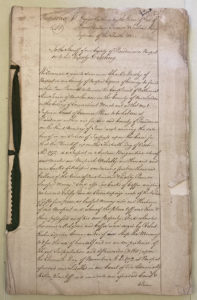

1774 Summary of Nathaniel Shaw vs. Charles Dudley, Newport Historical Society, Box 60, Folder 4.

On October 30, 1772, New London merchant Nathaniel Shaw imported 109 casks of molasses and two of coffee, at least some possibly from Guadeloupe, in violation of British regulations. According to Shaw’s attorneys, the combined value of the cargo, carried on a brigantine operated by one Michael Melally, was a whopping £1035– several times the value merchants like Shaw put on the lives of enslaved people forced to make their products. It is unlikely Shaw had any intention of paying the proper taxes on this. The Gaspee affair had occurred mere months earlier, and customs had been a heated issue since Britain sent warships to enforce long-overlooked taxes and then new ones in the mid-1760s. Still, not every British warship could be burned or boarded. Shaw had taken precautions– or rather, had Melally done so. When he reported to customs in Newport, Melally omitted Shaw’s 111 casks. He appears to have hidden them amidst his cargo as well- this was a disputed detail in the subsequent legal case, but it seems more likely than not given Melally took the known risk of coming into a well-policed port and lying about what his vessel contained. Melally “did Secrete & and conceal” the casks, according to the commander of the Mercury, whose men located and seized them.

Shaw appears to have been outraged that his illicit goods were seized. In November, he reported to the Vice Admiralty Court to claim his goods. A hated British institution structured to enforce equally hated customs regulations, the Vice Admiralty court ruled the goods were forfeit. Shaw responded by obtaining a writ from the colony’s Superior Court meant to return the goods to him based on what he argued were “Defects of Tryal” in the Vice Admiralty Court. In fact, the case was a dispute over fundamental political problems between colony and metropole

Shaw and the Superior Court rejected wholesale the authority of the Vice Admiralty courts. The writ, directed at Judge John Andrews and several others involved in the seizure, characterized the “Proceedings of said Court . . . altogether Illegal and against Right” on several grounds. First, an act of parliament from the thirteenth year of King Richard II’s reign- which spanned 1377 to 1399- “enacted and declared . . . that the admirals and their deputies should in no wise intermeddle” with anything not “done upon the High Sea.” They followed this up with a reference to another act made two years later indicating over “all manner of contracts pleas and plaints and of all other things done arising within the bodies of counties as well by land as by water . . . the court of admiralty should in no wise have cognizance power or jurisdiction.” This was frivolous, not least because there was a strong argument that what had occurred so far had happened upon the high sea. William Blackstone’s popular 1765 Commentaries on the Laws of England, which expanded and improved the accessibility of common law knowledge, explained for example that the water’s edge, tides included, was the boundary of admiralty jurisdiction.

But Shaw, his attorneys, and the Superior Court of Rhode Island were not arguing out of a principled belief in Ricardian legislation. Rather, this was an articulation of proto-revolutionary political discourse, which combined economic grievance, post-Seven Years’ War resentment, and legalistic anti-state sentiments grounded in cultural memory of the Civil War and the Glorious Revolution. In their writ of prohibition, the Rhode Island court’s judges indicated “the rights of our Crown + Custom of our Kingdom” as undergirding their authority to “prohibit the said John Andrews” from seeing the case or doing anything (implicitly, anything else) that was “to the Derogation of the Laws and Customs of England.” Their sweeping statements indicate the stakes of this argument, which was not really a debate between the competing values of customs legislation and expectations surrounding governors and naval commissions (another area of argument). Rather, this was an argument about what authority was just.

What became the central controversy of the case exemplifies the political conflict behind these events. Charles Dudley, Newport’s customs collector, purchased the confiscated goods on behalf of the Crown. The facts behind this purchase, from timing to legality to purpose, were extensively disputed. Numerous quibbles about process- appraisal timing, writ mechanics- were issued, but the harshest condemnations again concerned authority and jurisdiction. What Dudley saw as lawfully following the Vice Admiralty Court’s orders, Shaw argued was an illegal act that did “Dishonour [to] his Majesty’s service by Degrading his Principal Officers of the Customs into Petty Traders.” More bitter disputes arose over accusations of profiteering- that the “sale & purchase . . . is fraudulent and . . . perfected with intent to elude justice.”

Untangling the respective fact claims behind these arguments is a task beyond a short post like this, but the arguments themselves illustrate perspectives emblematic of the lead-up to Revolution. Dudley presented himself and probably saw himself as a dutiful officer of the crown. If he did engineer the sale in a manner to avoid the Superior Court’s interference, it would have been easy for such a man to justify this to himself as ensuring the lawful outcome by ignoring the compromised colonial court’s orders, which were after all in the interest of a known lawbreaker and subversive. Shaw meanwhile argued he was a wronged subject defending his rights against an overreaching bureaucracy. Americans who had long violated trade laws believed that the “benign neglect” and weak imperial authority of the pre-Seven Years’ War period represented their rights against the state, while British officials and sympathizers instead placed their faith in that state and the initiatives its new measures were meant to fund. Both sides might appeal in today’s parlance to the inability of making omelets without breaking eggs. For Tories, reforms that the ascendant post-war empire pursued were worth the cost of disrupting trade; for merchants like Shaw, continuing trade was worth the cost of ignoring recent enforcement measures by the state. Like the broader political controversy, their dispute seems to have been settled by force rather than words: Dudley appealed to the Privy Council and received a stay and a hearing in summer 1775. Probably without the issue being settled, he fled Newport in 1775 in the face of increasing animosity.

While each man presented himself as a justice-motivated ideologue and his foe as a cynical agent of greed, we should not reduce them to either. Shaw’s arguments about writs might have been sophistry, but his invocation of medieval law was not: it reflects both a self-interested desire to throw everything at the wall and see what might stick and return him his goods and an American political conviction that recent British policy violated ancient rights. The lines between theft and trade, between enforcing the law and expanding one’s wallet, were contested on both levels. So too was the broader conflict over colonial America’s fate– and the struggles over what kind of nation it would be. We should not forget that the contraband Shaw and Dudley were fighting over was created with coerced labor on stolen land. Their and the legal system’s failure to recognize this reflects not merely a self-interested denial of injustice, but also an ethical failing at the heart of both the mainstream Loyalist and Patriot political projects: while they argued over what freedom and justice meant, they denied both to countless people across the British Atlantic world.