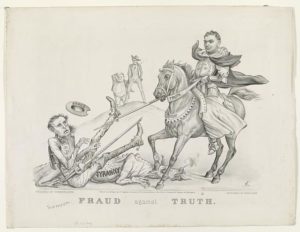

Currier & Ives. Fraud Against Truth. , ca. 1872. New York: Published by Currier & Ives. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2001699750/.

The fifth Civic Conversation tackled what was, apparently, the thorniest question so far: do we, in America today, have a shared set of facts and a shared vision of what is true?

The answer is both resounding and equivocal – no, we don’t. But. Given this, moderator Jim Ludes started us off with the most basic of questions. Is there a knowable truth? Is there a basic set of facts that we can agree to share? This is a deeply philosophical inquiry, one that is being discussed as a component of work done today in history, art, and other cultural endeavors.

“Science relies on verifiable facts,” said our first brave conversant, but people now seem to have difficulty distinguishing between a fact and an opinion. This led to a discussion of how we know, understand, or conceive of objective reality. And whether it exists outside of our personal perceptions. This is perhaps an unanswerable question, though we move through life generally with the assumption that it does exist, even if it cannot be proved. In doing this, some suggested, we rely on arbiters of the truth, experts, who stipulate to facts based on their research and expertise.

And in today’s America, those authorities have often lost their luster. The causes of this are, it seems, multiple. An eroding trust in authorities generally is pervasive, and this may have to do with all of the sources of information (good and bad) available to us. But we have also been exposed to the understanding of how our own preconceived worldview, and particularly our culture, mediates our views of reality, as different cultures literally perceive time and space differently. Even within 2020 America, it was noted, regional and cultural differences create different versions of truth. Does this lead us to simply throw up our hands on the idea of a shared reality?

More than once, the question was raised regarding the role money in our society may play in eroding our reliance on fact, as corporations buy scientific studies to say what will advantage them, political operatives move to influence the “truths” that we are offered on the news, and corporate media entities follow the desires of their audiences and their advertisers rather than the facts.

We have reason to be skeptical, it was suggested, but skepticism assumes that there is a truth beneath the spin. And, a reporter proposed, truth becomes better revealed when multiple sources are examined. This is the case for historians, too, as brief conversations about Christopher Columbus, Abraham Lincoln, and the history of our entrance into the Iraq War proved. Varying viewpoints may provide a more nuanced and “factual” version of past events. And the more we know, the more we can agree on what happened. But, the interpretation of why something happened may never have consensus and thus be much harder to consider as fact. Making these kinds of distinctions may help us to understand what we can agree on as established fact.

And, it was suggested, that agreement is part of how we construct our shared reality (whether, I will add, it exists objectively or not).

Concern was expressed about the way this dilemma affects our democracy. “When you don’t have social trust, when you don’t have a shared view of reality, do you even have a country?” said Farhad Manjoo in the New York Times, whom I cited in my introduction. Educating students to be good citizens of a diverse democracy probably requires helping them to distinguish between opinion and fact, to develop critical thinking skills and the ability to analyze sources, all critical components of a strong history education. In addition, one participant suggested, educating students to understand the appropriate roles of our various levels of our government, and being willing to talk about policies that do not challenge each group’s sense of reality, could be useful.

If we are all living in our personal realities, how do we get people today to step out of the reality that they have constructed for themselves, one participant asked? It is uncomfortable and requires an act of will.

Our moderators asked whether pockets of truth, or indeed any sources for optimism on this topic may exist today. One thought, by an historian in the group, was complicated but in fact very hopeful. It was suggested that one of our problems is that a limited perspective, which creates a limited subset of facts, gives us a picture that is incomplete. Historians have been rightly accused of creating narratives about our past that are not, in fact fully true, because of these limitations. But, today, we are working hard to create a broader base of information, from a variety of perspectives, and with a less biased eye. Or simply more eyes. This will give us better history, and better historical narratives going forward. This is a good thing. Another participant pointed out that since the historical narratives of the past were told to us as truth, but in being exclusive they were neither complete nor accurate, this has contributed to the suspicion of experts and arbiters of fact.

One conversant suggested that the suggestion that some of us have trouble distinguishing between facts and opinions is elitist. We are on the cusp of real societal change, they proposed, which causes many people a great deal of distress. We ought not to be making distinctions between some of us and others – all divisiveness is dangerous – and we can and should be hopeful about the future.

Jim asked a final question, one which will resonate with me as I think about this conversation over time. He posited that an essential component of civic health in a democracy is “the ability for a people to tolerate and process, not necessarily accept, but to process, views and personal truths in others that may be diametrically opposed to our own, with the understanding that we are going to settle it at the ballot box.” He asked if it was possible that the crisis was not with our truths, but rather with our democracy. When we have profound differences, and we have decided we are going to live together anyway, how do we do that? We do not seem to have settled comfortably on an answer to that in today’s America.

The influence of money, fear, loneliness, intolerance, and a lack of understanding of how our society is even supposed to work were all cited as components of our current unsettled state as we started to wrap this complicated conversation up. We ended by thinking about the fact that we may in fact be on the edge of change, and it may be towards a society that is more inclusive, honest, and “true.” I will add here that if we are, there is a lot of work to do, and conversations like this can be part of that work.

Banner: Deems, Jas. M. Buy the Truth, and Sell It Not. Deems, Jas. M., Baltimore, monographic, 1885. Notated Music. https://www.loc.gov/item/sm1885.04746/.