This is a guest blog post by Sam Dinnie (they/them), a PhD student in early American history at The George Washington University. Sam is a 2023 Buchanan Burnham Fellow.

The intricacies of loyalty and allegiance during the American Revolution are difficult to discern. From private correspondence to newspaper reports, written glimpses into the Revolutionary Era often portray the conflict as pitting Americans against Britons, Patriots against Loyalists. The historical narrative of the Revolution similarly tells the tale of two opposing sides fighting for clearly-defined ideals. This interpretation of the Revolution obscures the experiences of the politically ambivalent, divided, and disaffected, as well as the costs and complexity of declaring loyalty. To tease out these stories, one must read between the lines of Patriot and Loyalist sources and extract deeper meaning from expressions of partisanship. The lives recovered from a reevaluation of extant documentation helps to paint a fuller portrait of the American Revolution that amplifies previously muffled voices.

As part of a series exploring the complexities of political allegiance during the American Revolution, this blog post will examine how what is printed—and not printed—in newspapers can inform our understanding of political attitudes in Newport in the 1770s.

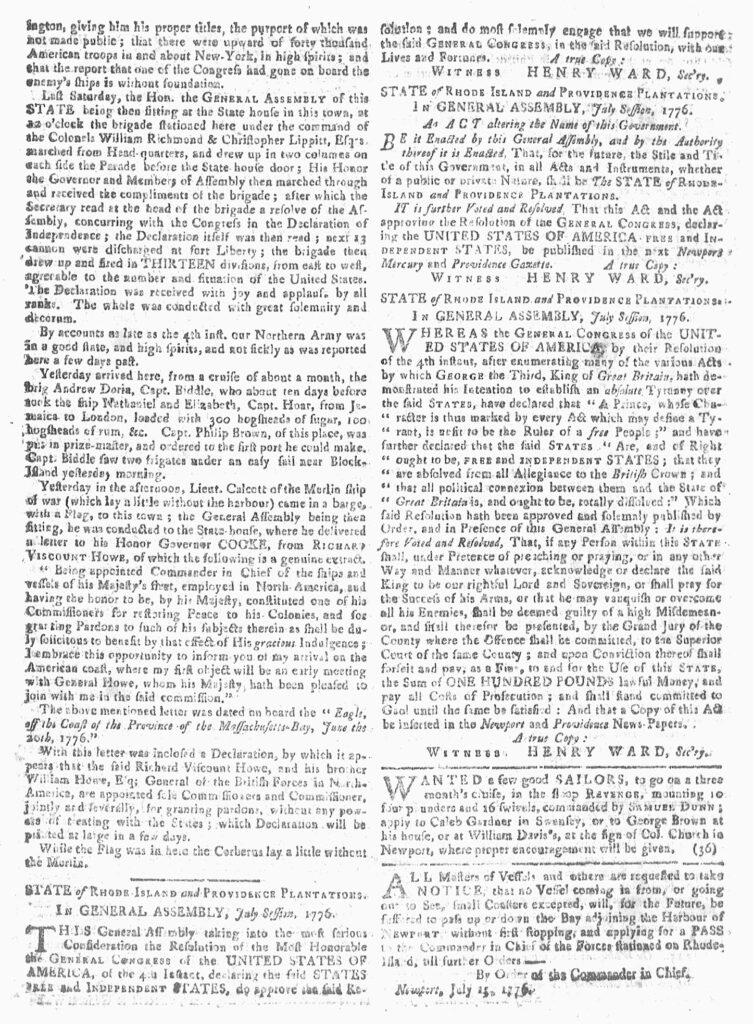

Patriot declarations in the July 22, 1776, Newport Mercury.

The July 22, 1776, edition of The Newport Mercury reported that the reading of the Declaration of Independence from the steps of the Colony House “was received with joy and applause by all ranks. The whole was conducted with great solemnity and decorum.”[1] Six months later, 444 Newporters sent an address to General Henry Clinton, commander of British forces in North America, that was printed in the first edition of the The Newport Gazette. Established by New Yorker and Loyalist John Howe in January 1777, Howe printed The Newport Gazette on the The Newport Mercury’s press. The Newport Mercury was suspended at the start of the British occupation of Newport in December of 1776 because of its Patriot sympathies. The address to Clinton is akin to a declaration of dependence, in which the anonymous signers professed their attachment to “the Blessings resulting from a constitutional Dependence upon the Supreme Authority of GREAT-BRITAIN” and pledged “all loyal and dutiful Allegiance to His Majesty KING GEORGE the Third” and obedience “to the Supremacy of GREAT BRITAIN.”[2]

Loyalist proclamation in the Newport Gazette, January 16, 1777, page 3.

That Newporters received the Declaration of Independence “with joy and applause” in July 1776 as reported by the Patriot Mercury and that General Clinton received the declaration of loyalty with “singular Pleasure” in January 1777 as reported by the Loyalist Gazette demonstrates the fluidity of political allegiance during the American Revolution.[3] So too does the Newport Mercury printing press changing hands from Solomon Southwick to John Howe shortly after the British landed on Aquidneck Island. During the Revolution, newspapers were both a critical source of information and primary conduit for disseminating partisan propaganda, a tactic employed by Patriots and Loyalists alike.[4] The Patriot description of the reading of the Declaration of Independence and Loyalist affirmation of allegiance were meant to communicate the strength of the respective causes in Newport, but the close chronological proximity of these Patriot and Loyalists attestations of supremacy reveals a community divided, if not in flux.

While these newspapers reflected the attitudes of printers and their desired audience, the ideological professions in town and regional newspapers give a false impression of the political views of a general readership. The American Revolution enveloped the entirety of British North America and left few communities unscathed by conflict. The totality of the Revolution, especially the Revolutionary War (1775–1783), placed immeasurable stress on individuals and families, prompting many to seek the protection of whichever side could provide stability, safety, and, for some, freedom.[5] Still others found themselves disaffected under the constant threat of violence from the Americans and the British, be it inflicted by ad-hoc Patriot committees of safety, British army regiments, or rogue armed bands of Loyalists.[6]

In an event as tumultuous as the American Revolution, choosing and expressing political allegiance was incredibly personal. Individuals factored in both practical considerations such as guarantees of protection and access to food and material supplies, as well as more introspective considerations of ideology and one’s relationship to family, King, and country. Newspaper reports like those in the Patriot Mercury and Loyalist Gazette shroud that complexity and depict Newport as a town united at the respective times of publication. The political reality of Revolutionary Era Newport can be deciphered through a close reading of print culture meant for public consumption, as it can through the consultation of private writings. Although still containing biases of the author, sources of the Revolutionary Era intended for a private audience introduce a different yet equally valuable way to make sense of political allegiance in Newport that promotes human connection.

[1] The Newport Mercury, July 22, 1776.

[2] “To his Excellency Henry Clinton” (address), The Newport Gazette, January 16, 1777.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Robert G. Parkinson, Thirteen Clocks: How Race United the Colonies and Made the Declaration of Independence (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press), 13–35.

[5] Francis D. Cogliano, “African Americans in the Age of Revolution,” in Revolutionary America, 1763–1815, 3rd ed. (New York: Routledge, 2017), 218–41.

[6] Alan Taylor, American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750–1804 (New York: W.W. Norton, 2016), 211–49.