This is a guest blog post by Sam Dinnie (they/them), a PhD student in early American history at The George Washington University. Sam is a 2023 Buchanan Burnham Fellow.

Political and military leaders of the opposing British and American forces understood that winning the Revolutionary War required more than military successes. General Henry Clinton, Commander in Chief of British operations in North America from 1778-82, determined that the British needed “to gain the hearts and subdue the minds of America.”[1] George Washington, Commander in Chief of the Continental Army for the entirety of the war, relied on “the Hearts of my American Brethren to support, and bestow sufficient Abilities on me to bring, the present contest to a speedy and happy conclusion.”[2] The strategy Clinton and Washington articulated was to secure the allegiance of the populace of the new United States. In waging rival campaigns for “hearts and minds,” distinguishing the loyal from the disloyal was paramount to victory.

Inhabitants of Newport faced the predicament of choosing loyalties during the war. Because of its strategic location and protected harbor, the British army and Royal Navy took Newport in December 1776 and began a three-year occupation. Shortly after the British arrived, Ezra Stiles, a firm Patriot—who was not living in Newport at the time but had sources keeping him informed of developments—reported in his diary on December 14, 1776, that “Proclamations of Pardon are stuck up all over the Town giving a space of 60 days.”[3] Those expected to sign the proclamations were likely active Patriots who had not yet fled town because they posed the greatest threat to Britain’s hoped-for reconquest of the rebellious colonies; to grant pardons to Patriot signatories was, as Clinton strategized, “to subdue the minds of America.”[4] By receiving a pardon from the British Crown, Patriots relinquished, in writing, allegiance to the United States, transforming them into Loyalist turncoats in the eyes of the new American nation.

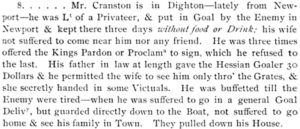

Excerpt from The Literary Diary of Ezra Stiles, Vol II, Page 123-124.

Patriots who refused to sign the proclamation could be punished. A “Mr. Cranston” visited Dighton, Massachusetts, where Stiles had taken refuge. In a February 8, 1777, diary entry, Stiles wrote that Cranston was “Lt of a Privateer” and was “put in Goal [jail] by the Enemy in Newport & kept there three days without food or Drink. . . He was three times offered the Kings Pardon or Proclama to sign, which he refused to the last.”[5] Stiles also noted that Cranston’s “wife not suffered to come near him nor any friend,” perhaps suggesting that wives of Newport Patriots during the British occupation were at risk of physical or sexual violence, which Stiles, documented to illustrate British barbarity.[6] Subjecting a Patriot’s family and friends to violence was one means of retribution the British employed; another was destroying personal property. Stiles explained that when Cranston “was suffered to go in a general Goal Delivy, but guarded directly down to the Boat, not suffered to go home & see his family in Town. They pulled down his House.”[7]

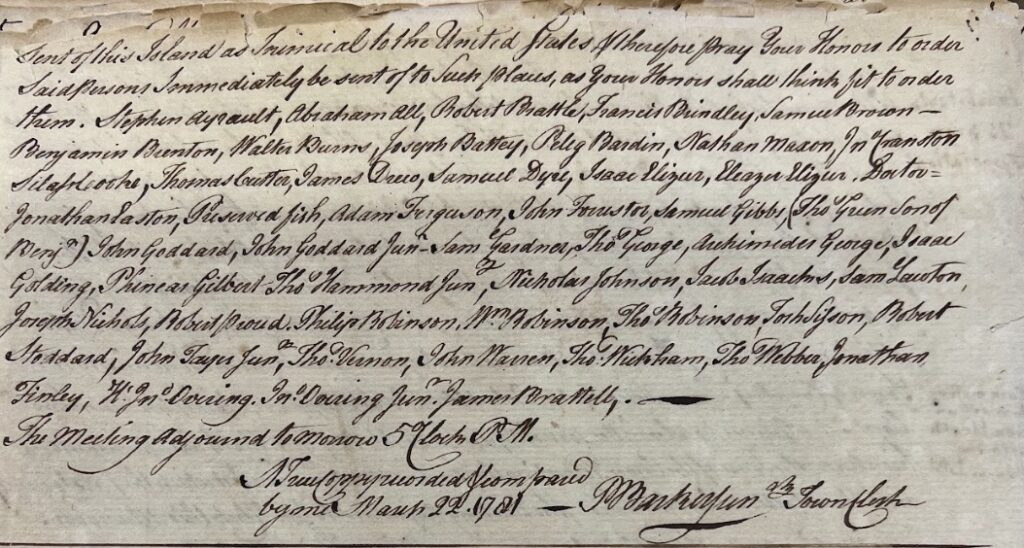

After the three-year British occupation (1776–79), American and allied French forces arrived in July 1780. That same month, the Newport town meeting voted to send a “Black List ” to the Council of War.[8] General William Heath of the Continental Army was also privy to the list as the town meeting voted that a committee of men “wait upon the Honble Majr Gen. Heath this afternoon to let him know the Sence of the Town, Respecting the persons Mentioned, in a list. . . Called the Black List.”[9] The introduction of the Black List stated “that the Freeman of the Town have this day Voted that the said Named Persons should be Immediately Sent of[f] this Island as Inimical to the United States.”[10] Of the fifty individuals identified as the most ardent and, therefore, the most dangerous Loyalists who could disrupt the new American and French order and compromise allied operations, the town meeting requested that the council “order Said Persons Immediately be sent of[f] to Such places, as Your Honors shall think fit to order them.”[11] The town meeting sought to clear Newport of the opposition so they and their collaborative occupying forces could control the town’s political allegiance to command support. Beyond removal and possible exile, by branding the people on the Black List enemies of the state at a critical point in the war, the town meeting set them up for possible imprisonment or death.

The “Black List”, which lists Newporters identified as Loyalists who were ordered to leave the town. Newport Town Council Records, Book 1, p. 7, Newport Historical Society.

It seems that Thomas Wickham, one of the men named on the Black List, was imprisoned for his accused loyalism. The General Assembly reported in 1781 that they received a petition from “Thomas Wickham, of Newport, now confined in the gaol at Newport” requesting that the Assembly release him from prison and waive the fine of “five thousand silver dollars.”[12] He attested that he was unable to pay the fine and “hath been imprisoned upwards of nine months” even though his sentence had only been six months.[13] The Assembly refused to grant the petition because the fine and other required bonds functioned as “surety, for his good behavior during the present war,” so they voted that “the said Thomas Wickham remain confined in the gaol at Newport, and there be closely kept until he shall pay. . . and give bonds as aforesaid.”[14]

The individuals for whose loyalty British and American forces were competing for undoubtedly felt insurmountable pressure in weighing their choices. In Newport, a town that twice changed hands, there could be dire consequences no matter their allegiance. Both opposing occupying forces were resolute on firmly securing Newporters’ loyalty as part of their hearts and minds strategy. Individuals who swung Patriot at the beginning of the war could be a target during the British occupation, and those who cast their lot with the British could suffer the consequences under American and French rule. For the politically ambivalent and disaffected, there was a constant possibility of their silence being interpreted as collusion with the enemy or that they would be forced to choose. By communicating the message that neutrality was not an option, British and American forces began to write the narrative of the American Revolution that portrays the conflict as a battle between their two clearly-defined sides.

[1] Henry Clinton quoted in Andrew Jackson O’Shaughnessy, The Men Who Lost America: British Leadership, the American Revolution, and the Fate of the Empire (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013), 220.

[2] George Washington to Landon Carter, April 15, 1777, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-09-02-0159.

[3] Franklin Bowditch Dexter, ed., The Literary Diary of Ezra Stiles (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1901), 2: 97.

[4] “Manifesto and Proclamation,” October 3, 1778, New York Historical Society Digital Collections. Clinton issued a proclamation of pardon to all the inhabitants of Britain’s former North American thirteen colonies in 1778, even civil and military leaders, so long as they terminated their service and reclaimed British subjecthood. The main message of Clinton’s “Manifesto and Proclamation,” printed in all capital letters, was that the British state “hereby grant and proclaim a pardon or pardons of all, and all manner of, treasons or misprisons of treasons, by any person. . . within the said colonies, plantations, or provinces, counselled, commanded, acted, or done, on or before the date of this manifesto and proclamation.”

[5] The Literary Diary of Ezra Stiles, 2: 123–24.

[6] Ibid., 123 (quote); Holger Hoock, “Jus in Bello, Rape and the British Army in the American Revolutionary War,” Journal of Military Ethics 14, no. 1 (April 2015): 74–97; Literary Diary, 2: 97. In the same diary entry that mentioned the proclamations of pardon, Stiles wrote: “Another came out of Newpt yesterday, says the [British] Soldiers ravished two Lying-in Women.”

[7] Ibid., 124.

[8] Abigail Adams to John Adams, June 25, 1775, Adams Family Correspondence (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1963), 1: 231–32; William Smallwood to George Washington, May 22, 1778, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-15-02-0191; John Williams to Benjamin Franklin, February 26, 1780, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-31-02-0400. The term “Black List” is not unique to Revolutionary Newport. Abigail Adams wrote to her husband John in June 1775 that “Mr. Boylstone and Mr. Gill the printer with his family are held upon the black list tis said.” On May 22, 1778, Brigadier General William Smallwood wrote to George Washington that he had “Transmitted Pope the black List & ordered them to be Apprehended to the Amount of Eighty.” John Williams wrote to his relative Benjamin Franklin in February 1780 that “I hope to God you never will See one of our Name enroled in the Black List of Traitors, to their Country.”

[9] Newport Town Council Records, Book 1, p. 7, Newport Historical Society.

[10] Ibid., 7–8.

[11] Ibid., 8.

[12] John Russell Bartlett, ed., Records of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations (Providence, RI: Alfred Anthony, 1864), 9: 463.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.