This is a guest blog post by Rebecca Farias, MA in History, Providence College. Rebecca is a 2022 Buchanan Burnham Fellow.

Growing up in Rhode Island and pursuing both my bachelor’s and my master’s in history from Rhode Island universities, I knew that historians and educators around the state have been working to research and promote a more thorough understanding of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) history. A quick drive around the state hints at RI’s diverse past: from familiar names such as “Metacom Avenue” and “Canonicus Street” to the Roger Williams National Memorial, to the Port Markers Project and the Rhode Island Slave History Medallions, which provide critical context at major slave trading sites. The state of Rhode Island is working diligently to reconcile its own heritage, both as a slave port and as a center of significant cultural diffusion, in order to re-center the colonial narrative around all Rhode Islanders.

Joining the Newport Historical Society this summer as a Buchanan Burnham Fellow, I quickly learned that some of the city’s most treasured historic buildings also function as points of contact with Rhode Island’s BIPOC heritage firsthand. Learning to write and deliver my own public history tours has granted me a sense of the significance of how we choose to interpret and present the properties, particularly with regards to how BIPOC individuals may have shaped the site in centuries past. Throughout the process of preserving, documenting, researching, and presenting the properties, the NHS acknowledges that the properties had been constructed from an entrenched social system that centers on whiteness and patriarchy.

Transparency in presenting this information is key to informing the public about the conflicts and contradictions inherent in Rhode Island’s historical relationship with its BIPOC residents. Sometimes the original sources for this information are unclear, so a nuanced approach is necessary when presenting to the public. For example, a primary source indicates that both Black and white laborers helped to construct the Colony House. The laborers appear to have been paid similar wages, however it is unclear if the Black laborers were free or enslaved- and if they were enslaved, if they were able to keep the wages. Without primary source support for this information, this part of the Colony House’s BIPOC heritage remains in question. Additional research in the local documentary records remains crucial, so that researchers can present the public with a more accurate timeline of BIPOC events, enriching Rhode Island’s understanding of its heritage. The more research that historians, genealogists, and other researchers conduct, the more comprehensive Newport’s history becomes.

A photograph depicting the Seventh Day Baptist Meeting House after its move to Touro Street. The building is currently attached to the Newport Historical Society headquarters. P1580, Collection of the Newport Historical Society.

Another NHS property served as a more in-depth point of contact for white and BIPOC individuals. The Seventh Day Baptist Meeting House contains a long and proven timeline of BIPOC participation and even religious leadership, including that of free and enslaved Black people and Native Americans. Enslaved men and women and Native American people are included unambiguously among the Church’s early written rosters. According to Janet Thorngate, author of the article Slave or Free? African-Americans in the Newport Seventh Day Baptist Church, there were at least 11 Black people baptized into the church over its 123 period of history.

Although it is not known exactly how many Indigenous people were baptized into the church, one of the three earliest baptisms into the Sabbatarian religion was a Native American boy named Jepheth, sometimes referred to as Japeth. He appears in the Seventh Day Baptist records as a servant or slave to Jonathan Rogers; Jonathan himself was baptized in New London, Connecticut, in 1674. Jonathan took Jepeth to be baptized in Westerly, Rhode Island in 1675, Although the baptism did not take place in Newport, the congregation consisted of some of the Sabbatarians that would later come to practice in Newport, first worshiping at a building at Green End, before eventually constructing the Seventh Day Baptist Meeting House in 1730. Although records remain limited, Jepeth became one of the first congregants to receive a “letter of reproof” from the church elders “for growing cold & vain.” Little else is known about what befell Jepeth, but his enslaver Jonathan Rogers later drowned in a hunting accident.[1]

The rosters also reveal Black church members such as “Pegge” Arnold, enslaved by the grandfather of the infamous Revolutionary War traitor Benedict Arnold, and Arthur Flagg (who also went by Arthur Tikey) who was a member of Newport’s Free African Union Society. Founded in 1780, this Society was the first all-Black cultural institution of its kind in the United States and served to provide mutual community aid in the form of spiritual, domestic, and economic assistance to its members.

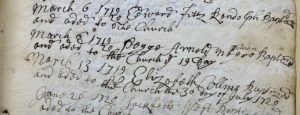

The baptism record of Pegge Arnold, March 6, 1719. Vol. 1400, page 18. Collection of the Newport Historical Society.

Both Pegge Arnold and Arthur Tikey are interred in God’s Little Acre, a nearby burying ground that remains the largest and most intact collection of seventeenth and eighteenth-century graves of free and enslaved African Americans.

After the Revolution and the subsequent occupation of Newport by the British, many congregants fled for safer areas; church services were abandoned by the late 19th century. During the turmoil of the Civil War, the Seventh Day Baptist Meeting House was habitually loaned out to members of the Shiloh Baptist Church, a primarily Black congregation, for their own worship. Although we possess a limited record of these events, that which is largely confined to church rosters and grave markers, it is imperative that historians continue to learn and teach how Black individuals and other people of color practiced self-advocacy by utilizing the Seventh Day Baptist Meeting House and other local heritage properties.

[1] Janet Thorngate, Baptists in Early America, Vol. III: Newport, Rhode Island, Seventh Day Baptists, ed. Janet Thorngate, (Mercer: 2017), 58-59. See also James Rogers, James Rogers of New London, Connecticut, and his Descendants, (Boston: 1902), 46.