This is a guest blog post by Maureen Iplenski, MA/PhD in History, American Studies, Certificate in Museum Studies (expected 2026) University of Delaware. Maureen is a 2022 Buchanan Burnham Fellow, contributing towards the “BIPOC Biographies from the Archives of the Newport Historical Society” initiative.

In the 18th-century, Newport was recognized as the fifth largest city in Colonial America. With a bustling port, many Newporters were able to gain considerable wealth through trade. In fact, by mid-century Newport became a key port within the triangular trade, which is a system that brought people from Africa to the Americas, where they were forced into enslavement. Domestic trade also flourished in Newport at this time. Mariners were able to earn wages by working on ships that travelled to the South, where cloth, foodstuffs, and rum – among other products, were sold. Ships that travelled along these trading routes frequently brought enslaved Africans directly to Newport, as well. By the mid-century, between ten to twenty percent of Newport’s population were people of color, most of whom were enslaved. [1]

As Newport served as a commercial center for the American colonies, those who remained in town also came to benefit from this trade. Women in particular were able to enjoy economic freedom at home. With their fathers, husbands, and brothers off at sea, Newport’s women assumed greater power over their households. They managed boardinghouses, completed domestic laborer, and worked as schoolteachers in order to financially support themselves and their families. [2] Women also asserted their authority as enslavers. According to the 1782 Rhode Island census, over twenty percent of Newport households with peoples of African descent and Native Americans were headed by white women.

Among these women was Catherine Coddington. She lived with three other women, two of whom were her sisters, along with one young boy and an enslaved man of African descent. [3] In 1778, Catherine’s brother, John Coddington, passed away. In his will, he requested that his “Negroes or Mullatoes, namely Jack, Pegg, [and] Andrew [go to] Katherine, Mary, and Susannah Coddington until they arrive at the age of thirty years and then to be set free.” [4] The one person of African descent in Catherine’s household is presumably either Jack, Pegg, or Andrew. As the 1790 Census no longer shows a Black person in her household, it is likely that that he reached the age of thirty, and was therefore manumitted.

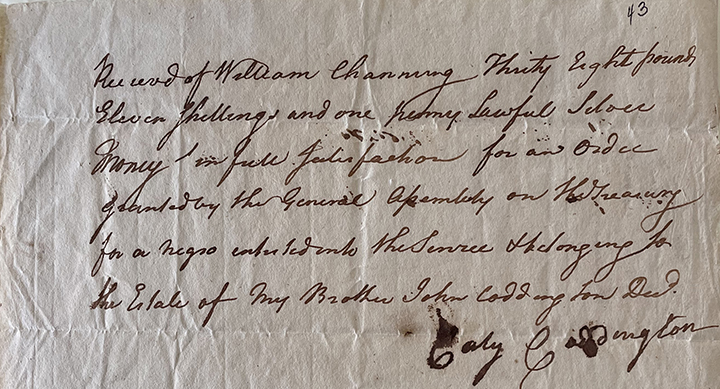

Catherine did not just benefit from the physical labor of an enslaved man. She also received some wealth from this system of slavery. A receipt between Catherine and William Channing shows that she received 38 pounds, 11 shillings, and 1 penny when an enslaved person formerly owned by John Coddington (then deceased) was enlisted into service during the American Revolution. According to an amendment passed by the Rhode Island State Government in October 1778, when an enslaved person enlisted into the Army, the enslaver was to receive “the whole or any part of the value of their slaves.” [5] The value of enslaved persons was determined through an appraisal process conducted by the General Assembly. This cost was meant to compensate enslavers for their “lost property” and lost labor. Considering that John passed prior to receiving these funds, Catherine reaped the financial benefits of his enslaved man’s service. Catherine demonstrates her financial independence in this exchange, as she recorded the transaction and confirmed that Channing, in fact, paid her the proper amount.

Receipt between William Channing and “Caty” Coddington, NHS Slavery Documents, Box 43A, Folder 26, Collection of the Newport Historical Society.

Women in Newport, similar to Catherine, often came to own enslaved persons and property when a husband, brother, or father died. In another instance, Lucy Ann Coggeshall headed a household with 13 people – two of whom were identified as enslaved people of African descent. Two of the women listed in the 1782 census are her daughters, Annie and Abigail, who were identified as “spinsters” in the land records. When Lucy’s husband, Daniel, passed away in 1777, he willed her and her daughters his lot of land located on East Thames Street. The 1774 census also states that Daniel had three enslaved people in his household. It is likely that two of these individuals were kept in Lucy’s household following his death. Although women did acquire enslaved laborers through their own means, the 1782 Census demonstrates that women with a Native American or Black person in their household were frequently widowed. Their widowhood suggests that a portion of these enslaved persons were either acquired through the will of a husband or purchased following the death of their husband.

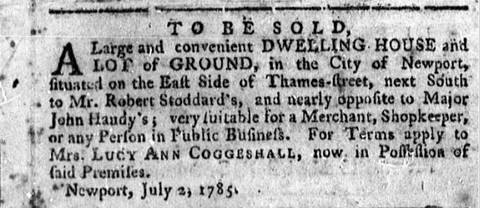

The act of receiving enslaved laborers and property through her spouse, however, should not discount the economic power that Lucy, along with other Newport women carried. An advertisement, which was published in the Newport Mercury, reveals one way women utilized their inherited property to earn wealth for themselves. In 1785, Lucy Ann announced that she was selling her dwelling house on East Thames. Lucy, along with her two daughters, eventually sold the property to a Robert Bratten in 1787.

Newport Mercury, July 2, 1785

Considering that Lucy was then a widow, and her two daughters unmarried, these women remained in each other’s household up until Lucy’s death in 1790. By heading their household together, these three women were able to create a support system for one another. As single women in 18th century Newport, Lucy, Abigail, and Annie likely faced economic risks. “The evolution of the city’s economy toward commercial capitalism [however] presented these women with a widened array of means to survive, whether by choice or circumstance, outside the bounds of matrimony,” proclaims the historian Jonathan Beagle. [6] Women were able to alleviate this economic risk, partly by depending on enslaved laborers.

The freedoms of Native Americans, along with people of African descent, were often sacrificed to serve the needs of white women. “Indeed, the slave presence in Newport was a potential source of physical, emotional, and financial help to the area’s widows,” states Beagle. White women held men, women, and children in bondage; they forced them to complete manual labor; and they sold or leased out their enslaved persons to other enslavers, thus perpetuating this system of slavery. From such practices, female enslavers received significant payments. As women took over economic responsibilities for themselves and their families, with the agency and freedom that this conveyed, they often also became more active participants in the system of enslavement that appropriated the labor and freedom of others.

[2] Johnathan M. Beagle, “Waves of Change: Women, Work, War, and Wedlock in Colonial Newport, Rhode Island, 1750-1775″ (MA Thesis, University of Rhode Island, 1997).

[3] Jay Mack Holbrook, Transcriber. Rhode Island 1782 Census (Oxford, MA: Holbrook Research Institute, 1979).

[4] John Coddington, January 29, 1779, Rhode Island, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1582-1932. Accessed on Ancestry.com. https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/discoveryui-content/view/2365:9079?tid=&pid=&queryId=a79e4e19263a3d60c78dde60f2732d4f&_phsrc=ShY425&_phstart=successSource

[5] Read Amendment in full: RI Department of State, “Owners of Slaves to Be Paid.”

[6] Jonathan M. Beagle, “Waves of Change.”