This is a guest blog post by Sam Dinnie (they/them), a PhD student in early American history at The George Washington University. Sam is a 2023 Buchanan Burnham Fellow.

The typical understanding of political allegiance during the American Revolution as binary—Patriot or Loyalist, American or British—obscures the very real tribulations people experienced and dismisses fluctuations in loyalty as the Revolution evolved. Sources intended for a private audience reveal how personal, introspective, and complex ruminations about political allegiance were. Analysis of private sources can thus enable one to forge an empathetic connection with the writer(s) that enlivens their story, allowing us as readers to better understand the complexity of loyalties in the Revolutionary Era.

The outbreak of the Revolutionary War in April 1775 escalated pre-war tensions and impelled inhabitants of British North America—perhaps for the first time since the imperial crisis began in the 1760s—to consider the issue of loyalty. As individuals contemplated political leanings, many prioritized their own personal, material, and practical circumstances over ideological doctrines that Patriot and Loyalist elites championed. Gender, race, religion, socioeconomic status, and geographic location, as well as how imminent the threat of violence was, all influenced a person’s political allegiance, or lack thereof. These considerations were especially pertinent in a town as turbulent as Newport.

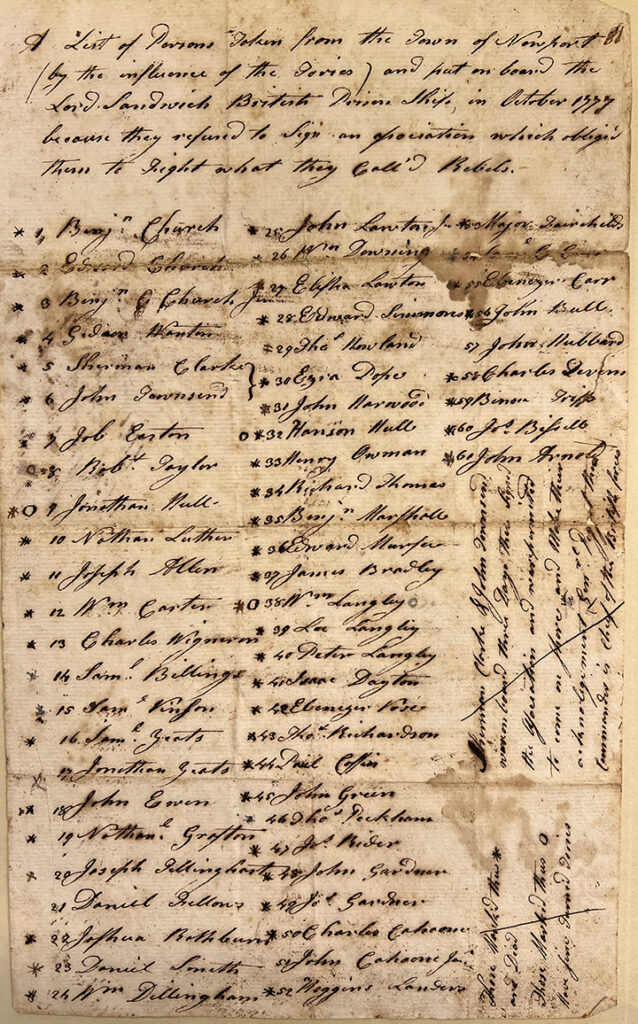

“A List of Persons Taken from the Town of Newport (by the influence of the Tories) and put on board the Lord Sandwich British Prison Ship in October 1777,” Vault A, Box 123, Folder 21, Newport Historical Society.

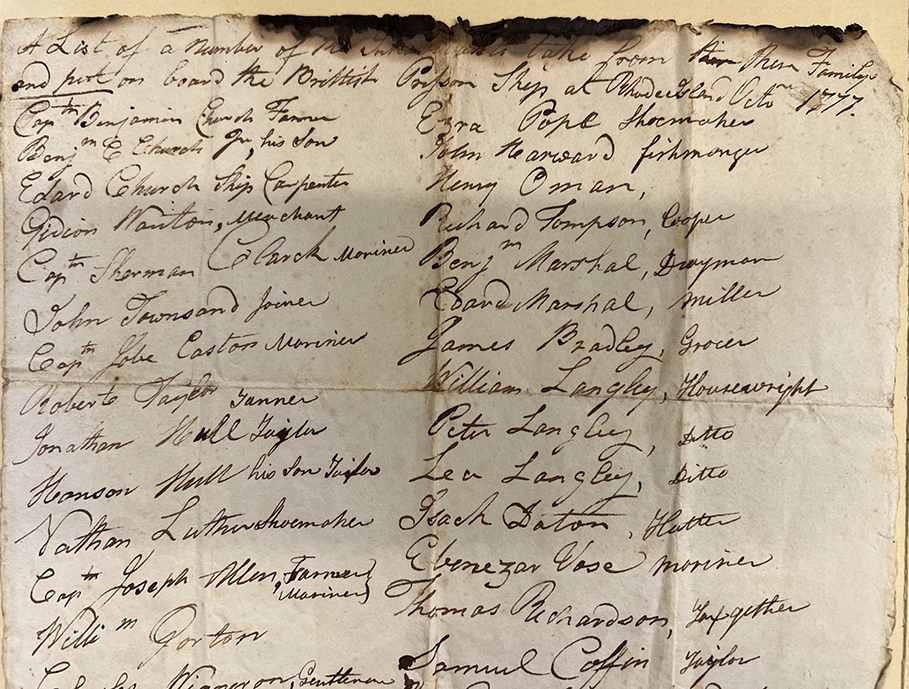

As pacifists unable to swear oaths of allegiance, Quakers remained vulnerable throughout the Revolution. Shortly after the British began their three-year occupation of Newport in December 1776, some Quakers determined that the British were the better option for guarding their livelihoods and decidedly recorded an address to General Henry Clinton in their meeting minutes. The seventy-six signatories attested that “We the Kings peacable & Loyal Subjects being deeply affected with the unhappy Commotions which now prevail around us. . . [none] of our Members and have publickly manifested our disunity with such have appeard openly in taking up Arms. . . . thereby we ask the protection of our persons & properties & indulgence in the enjoyment of our Religious Liberties.”[1] It is unclear whether or not the Quakers formalized their private address into a dispatch to Clinton; either way, their assurances did not shield them from British wartime action and perhaps stoked retribution from allied American and French forces who took possession of Newport in 1780. Adhering to the pacifism of their faith, several Quakers—as well as non-Quakers—were detained on the British prison ship Lord Sandwich in October 1777 “because they refused to sign an appreciation which obliges them to Fight what they call’d Rebels,” and a few were likely among the numerous casualties inflicted by the squalid conditions of prison ships.[2] One register of the prisoners is labeled as “A list of a number of the Inhabitants taken from their Familys and put on board the British Prison Ship at Rhode Island,” emphasizing the incredible stress the Revolution placed on familial relationships.[3] Four years later, the French seized the Great Friends Meetinghouse but were compelled to return it upon the governor’s intervention.[4] The Quakers’ plight exhibits the stakes involved in expressing loyalty in an event as tumultuous as the Revolution.

Miniature of Mary Gould Almy by Edward Greene Malbone, circa 1797–1800. The Rienzi Collection, bequest of Caroline A. Ross, 2005.1604. The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

Mary Gould Almy’s experience likewise illustrates the personal nature of political allegiance. Mary, a baptized Anglican at Trinity Church, operated a boarding house on Thames Street in Newport throughout and following the British occupation.[5] Mary pronounced herself loyal to Britain while her husband, Benjamin, enlisted as a privateer for the American cause.[6] Her ordeal proved far more elaborate than a house divided, as her diary reveals. As she and countless others endured years of violence and instability, the divisions that occupied their minds were not always political. As Almy articulated in her diary, those weathering the storm prioritized the reunification of families torn apart by wartime strife: “ten thoussand Wellcoms to the long lost Wanderers Parents receiving there chilldren from loathsom Prissons — wifes there long banish Partners from all they held dear — brothers and Sisters kindly meeting — after a tedious Absence.”[7] Almy doubtless penned those words reminiscing about her distant husband, and she elevated her affection for him above their opposing loyalties. Although she informed Benjamin in a prefatory note to her diary that “my dislike to the Nation that you call your freinds is [the] Same as when you knew me,” how she had suffered in August 1778 during the allied French and American siege of British-occupied Newport inspired her to profess: “heaven I hope will Support you — So Possitive So Assured of Success — and remember. . . our Patience in waiting — will be amplely repaid — by a joyfull meeting.”[8]

“A List of a Number of the Inhabitants take from Their Familys and put on board the British Prison Ship at Rhode Island Octr 1777,” Vault A Box 123, Folder 21, Newport Historical Society.

The Quakers and Mary Almy are but two examples of Newporters who had to confront what political allegiance meant to them. The Revolution engulfed all of British North America, and the conflict’s totality left the populace of the United States little choice but to decide where their loyalties and priorities lie. People understood that the looming uncertainty of an unpredictable war meant who was in control of their communities was subject to rapid change and that both their personal safety and the fate of loved ones was constantly in the balance. Keeping political allegiance private, therefore, could be regarded as an act of self-preservation.

The already stressful task of determining loyalties was often compounded by vocal Patriots and town officials seeking to root out suspected Loyalists. The intimidation and pressure caused by policing political allegiance adds yet another layer of complexity to deciphering political allegiance in Revolutionary Newport.

[1] Elaine Foreman Crane, A Dependent People: Newport, Rhode Island in the Revolutionary Era (New York: Fordham University Press, 1985), 134; “The address of the people called Quakers on Rhode Island,” January 2, 1777, Society of Friends Minutes of Meetings, 1773–1790, Book 810, 103, Newport Historical Society.

[2] “A List of Persons Taken from the Town of Newport (by the influence of the Tories) and put on board the Lord Sandwich British Prison Ship in October 1777,” Vault A, Box 123, Folder 21, Newport Historical Society.

[3] “A List of a Number of the Inhabitants take from Their Familys and put on board the British Prison Ship at Rhode Island Octr 1777,” Vault A Box 123, Folder 21, Newport Historical Society.

[4] Arthur J. Mekeel, The Relation of the Quakers to the American Revolution (Washington, DC: University Press of America, 1979), 222.

[5] John B. Hattendorf, ed., Mary Gould Almy’s Journal, 1778 (Rhode Island Society Sons of the Revolution, 2018), 17–20.

[6] Ibid., 14

[7] Ibid., 69.

[8] Ibid., 25; Ibid., 83.