This is a guest blog post by Rebecca Farias, MA in History, Providence College. Rebecca is a 2022 Buchanan Burnham Fellow, contributing towards the “BIPOC Biographies from the Archives of the Newport Historical Society” initiative.

The NHS holds a document with relevance to the COVID-19 pandemic: a handwritten 1772 roster titled “A List of Persons Carried Away with the Small Pox to Coasters Harbor.”[1] Smallpox epidemics hammered New England throughout the colonial era, with deadly outbreaks occurring in 1649, 1655, 1678, 1690, 1702, 1721, 1730, and 1752, and with more severe epidemics in 1760 and 1770-1778.[2] Physicians urged inoculation and even tried to institute a “six foot rule” for protection, but, not unlike today, colonists pushed back against medical interventions into their private lives. As Rhode Island’s busiest port, Newport was forced to come up with steps to protect citizens from incoming mariners carrying the disease. Their solution was to quarantine patients and those exposed to the contagion.[3]

In 1716, the government ordered the construction of a “hospital” on Coaster’s Harbor Island, a 92-acre island in Narragansett Bay that now houses the Naval War College. Unlike modern medical facilities, colonial hospitals existed mainly to isolate the infected, where they would receive care from others who had already survived smallpox, thus gaining immunity. This 1772 roster allows historians to piece together the demographics of some of the patients, showing that smallpox struck indiscriminately, regardless of age, class, gender, or race.[4]

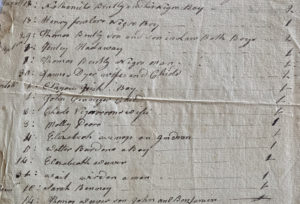

The list bears the name of 33 people exposed to smallpox who were relocated to “Coaster’s Island” over the course of August 1772 to December 1772. Some faced relocation alone, such as “Molly Peare” and “Marry Godard.” Others were accompanied by family members, young and old: “Thomas Weaver and Mother” went to Coaster’s Island on November 15, while “Joseph Nichols Daughter Elizabeth” relocated on November 22. Still others are not recorded with a name, instead reduced by the record-keepers to their social standing. “Aaron Sheffield wife” joins the ranks of patients with “Daniel Sheffield’s child.”[5]

Some of the individuals recorded in the “List of Persons Carried Away with the Small Pox to Coasters Harbor” (1772). Box 114 Folder 14, Collection of the Newport Historical Society.

This smallpox list is also noteworthy because it records the race of quarantined individuals, allowing historians to understand the linguistic parameters of describing patients’ ethnicities and social status. The list contains several references to enslaved individuals, whom the record-keepers often referred to as simply “Boy” or “Man” in association with their age and social position. Eliyou Irish… Boy.” The smallpox list also records “Nathaniel Bentley and his Negro Boy.” In the 1774 Newport Census, Nathaniel Bentley is listed as having no enslaved people in his household, suggesting not only that Bentley survived the smallpox, but that Bentley’s enslaved person did not survive to be recorded by the census, or perhaps was sold. Whatever the case, Bentley did not register any enslaved people in the census that year.

Alternatively, Thomas Bentley, whose “Negro Man” was relocated to Coaster’s Island by himself, may have been recorded in the 1774 census, as this data shows that Bentley held two enslaved Black men over the age of 16 at the time of recording. However, it is difficult to discern whether these could be different people than the enslaved man Bentley sent to Coaster’s Island. The record also refers to “Elizabeth Wenop an Indian,” which confirms her Indigenous identity even though no other description is given, and no record of her death could be found. Indeed, smallpox was a great social leveler, as is the case with all epidemic diseases of this scale and magnitude.[6]

Quarantine may have provided a short-term solution, but death rates were staggering: in 1722 in Boston, the fatality rate was nearly 21% of those who contacted the disease.[7] The Newport government designated the area that would become the Coaster’s Island Smallpox Burial Ground for the internment of victims’ bodies, since even after death, they were considered a public hazard. The earliest marked gravestone dates from 1736, but historians estimate that several unmarked graves might predate that headstone. Most of the gravestones are now eroded, but a 1917 Navy inventory provides crucial historical insight into the lives and deaths of the interred victims.

The inventory records 62 smallpox victims in the cemetery, at least those whose stones could be deciphered in 1917. The oldest victim recorded is Millie Babcock, who died in 1878 at the age of 102; the youngest victims were 22 years old. Sometimes entire families succumbed to the disease; Marcy Shaw, also known as Rebecca, died at the age of 25 in 1761 and is buried with her two-year-old son and nine-month-old infant. Some of the stones provided religious designations, for example, if the victim was a Baptist or a Quaker. Further research into the lineage of each person listed could provide more context into their lives. But for now, historians utilize this cemetery inventory and documents such as the relocation list to understand how death and contagion affected colonial Newport, in strikingly similar ways to today.[8]

[1] Newport Historical Society, A List of Persons Carried Away with the Small Pox to Coasters Harbor,” 1772. Box 114, Folder 14.

[2] Rhode Island Genealogical Society, Newport, Rhode Island: Colonial Burial Grounds, (2009), 411.

[3] Rhode Island Genealogical Society, Newport, Rhode Island: Colonial Burial Grounds, (2009), 411.

[4] Colonial Burial Grounds, 411.

[5] List of Persons Carried Away with the Small Pox to Coasters Harbor

[6] List of Persons Carried Away with the Small Pox to Coasters Harbor

[7] Per-Olaf Hasselgren, The Smallpox Epidemics in America in the 1700s and the Role of Surgeons: Lessons to Be Learned During the Global Outbreak of Covid-19, (NCBI: 2020), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7335227/

[8] Colonial Burial Grounds, 412-413.