Zoe Hume, MS graduate, Florida State University, is one of the 2021 Buchanan Burnham Fellows working on capturing data from the NHS archives on Black and Indigenous people of color in colonial Newport, Rhode Island. The following post relates to the naming of enslaved individuals as they appear in the historical record.

Discussions of the importance of names, and respecting someone’s name, have been on the rise in recent years, particularly in light of the growing recognition of the world’s transgender and nonbinary populations. The act of deadnaming refers to either accidentally or intentionally using a name that someone no longer identifies with. And while we largely associate this concept with LGBTQIA+ rights, it is far from the first time we have called the importance of names in question.

As a summer fellow with the Newport Historical Society, I am working to uncover the names of Rhode Island’s 18th century enslaved, indentured, and manumitted population. Though my work has only just begun, I already face a weighty question, “If you cannot ask someone, can you ever really know their name?”

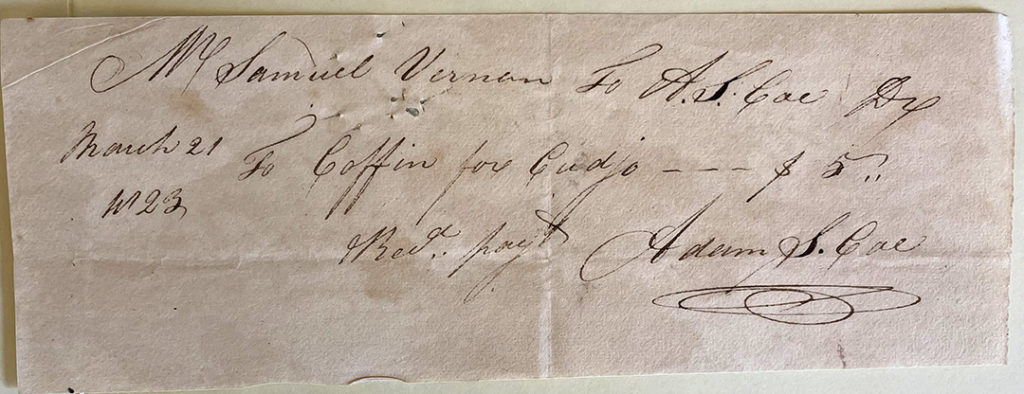

Consider, for example, this letter from Samuel Vernon to coffin maker Adam S. Coe buying a coffin for Cudjo on March 21st, 1823. Cudjo is an Anglicized version of the birthday name Kojo or Jojo (from the Twi dialect) or Kwadwo (from the Fante dialect), all of which come from the Akan language and are for boys born on Monday1. The Akan people have a long history in West Africa, particularly Ghana and the Ivory Coast, but because of their naming traditions, we can find evidence of their enslavement in the Americas.

Letter from Samuel Vernon to coffin maker Adam S. Coe buying a coffin for Cudjo on March 21st, 1823. Box 43A, F26, NHS Collection.

On March 26th, 1823, an obituary for Cudjo Vernon appeared in The Rhode-Island Republican, and the author identified Cudjo as “an African by birth….” Is Cudjo an Anglicized version of this person’s birth name? Just as someone might make the choice to change their name, names change over time and across cultures. It is common for names to have different versions depending on the language or for people to adapt their names to suit their environment. But is it possible that Cudjo is just a name his enslaver gave him? Even if he was born on a Monday is a mystery to us.

Whether Cudjo was in any way close to his African birth name or just a name assigned to him with no regard for meaning or his own preference, on November 11th, 1782, Cudjo Vernon wrote to Samuel Vernon III asking for permission to marry a woman named Sylvia (Newport Historical Magazine in 1884, no. 4, pg 202). He signed the letter “Cudjo Vernon.” That he signed at least one of his own letters with the name Cudjo Vernon shows that, at that moment in 1782, he was willing to identify himself with that name. Yet can we consider a letter to an enslaver a decisive indicator of an enslaved or freed person’s preferred name? Did his friends and wife also call him Cudjo? How would he want to be remembered?

For every name we find in our archives, and for every unnamed entity, there is a person with thoughts, feelings, and a story we may never fully know. Some, like Cudjo, leave behind artifacts that let us know that at a particular moment they identified themselves with a certain name, though there may be complex reasons behind such a decision. Others are either unnamed or only known by the name assigned by a slaveowner. Whether we know their preferred name or have no name for them at all, the database this project will reflect the existence of Rhode Island’s enslaved, manumitted, and free populations on an individual level, drawing a person’s unique story out of the depths of historical obscurity, no matter how fractured or incomplete that story may be or how many questions we are left with.

[1] Agyekum, K. (2006). The sociolinguistic of Akan personal names. Nordic Journal of African Studies, 15(2), 359-74. http://www.njas.helsinki.fi/pdf-files/vol15num2/agyekum.pdf