Miniature painting of John Handy, a Major during the Revolution. On July 19, 1776 he read the Declaration of Independence from the balcony of the Colony House; 50 years later, he repeated the performance. 76.1.1, Collection of the NHS.

July 20, 1776 – The first celebration of Independence from Great Britain in Newport, Rhode Island occurred on July 20, 1776, when Major John Handy of the Continental Army read the Declaration of Independence to the citizens of Newport from the Colony House. According to the local paper, The Newport Mercury, “The Declaration was received with great joy and applause by all ranks. The whole was conducted with great solemnity and decorum.” A discharge of 13 cannons and a military salute fired in 13 divisions, representing the 13 original states, followed the reading of the Declaration. British forces occupied Newport shortly after Major Handy read the Declaration from the Colony House and these troops remained in Newport for three years causing considerable amount of devastation. (The Newport Mercury, July 22, 1776)

July 4, 1781 – Colonel Crary, head of the local militia, held a dinner party on July 4, 1781, for French officers who were stationed in Newport during the war. After the occupying British troops left Newport, our French allies sent troops to the town in July of 1780, under the commanded of General Rochambeau. It was his officers who were invited to this special dinner. Upon the completion of dinner it was customary to drink 13 toasts, accompanied by artillery fire. The list of toasts from Col. Crary’s dinner was published in The Newport Mercury and it included, “The King of France and his Allies…the Governor and Company of the State of Rhode Island…George Washington and the allied Army…General Rochambeau…A Successful Campaign…The friends to the Natural Rights of Mankind.” The Newport Mercury reprinted the toasts from one select dinner party a year in the newspaper in the 1700s, so the toast subjects were carefully selected before the list was submitted for publication. (The Newport Mercury, July 7, 1781)

July 4, 1793 – By the 1790s, Newport celebrated the Fourth of July with more structured and events than in previous years. The celebration in 1793 included a dinner at the Colony House for members of the Newport Artillery Company. The Colony House was decorated for dinner and The Newport Mercury wrote of one unique local tradition, which involved placing a tree inside the Colony house and decorating it with flowers to mimic the real Tree of Liberty. According to the paper, “A very elegant dinner was provided in the Assembly Room; in the Centre of which there was Tree in the freshest verdure, the Top of which reached the Ceiling, and its Branches, widely extended, were decorated with the greatest Variety of Flowers; – emblematical of the Tree of Liberty in its most flourishing State.” The gentlemen drank 15 toasts that year rather than 13 because of the addition of Kentucky and Vermont to the original 13 states. (The Newport Mercury, July 9, 1793)

On Independence Day in the 1790s, the bells of the Colony House were rung on a specific schedule.

The town bells ringing on Fourth of July in Newport appeared in reports from The Newport Mercury in early celebrations and they remained an important part of Fourth of July festivities for many years. The bells rang on a very strict schedule and at established times of day. A handwritten letter possibly written by William Vernon around 1790 explains the bell ringing schedule precisely, “The bells to be Rung on the 4 July as follows – at brake of Day, or that the Gun’s firing at the Fort to be Rung half an Hour – at nine o’clock to be Rung fifteen moments – and to Commence Ringing again when the prosession Gets in the Meeting house – After the Oration and Service is finished, the prosession will be formed and the bells will commence Ringing and continue until the prosession are on the parade + dismissed – at Sunset they will Commence Ringing and Ring half an Hour – the bell at the Statehouse will give the signal when to Ring + when to cease Ringing.” Fourth of July celebrations had the potential to get out of hand without rules and regulations. Notes and instructions, such the Vernon letter, helped to provide participants in Fourth of July events with guidelines to ensure order throughout the festivities. (The Vernon Letter, circa 1790)

July 4, 1794 – A clearly defined schedule kept Fourth of July celebrations orderly and dignified. Maintaining order during the Fourth prevented accidents, but even the best laid plans could go awry, as The Newport Mercury reported in 1794, “We are sorry to add, that the general Joy and Happiness, which had prevailed through the Morning, was allayed by an Accident which happened in the Afternoon, – A keg of Cartridges, at the Foot of Louis Street, accidentally took Fire and by the Explosion several Men and Boys were wounded. Two of the Lads, we learn, are dangerously hurt.” Guns and cannons were a central part of many early Fourth of July celebrations, but storing so much gunpowder in one place, without taking proper care around the substance clearly posed risks. (The Newport Mercury, July 6, 1794)

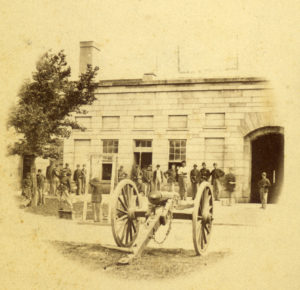

Artillery and cannon fire became a fixture of Newport’s July 4th celebrations. P5231, Collection of the NHS.

July 4, 1809 – By the early 1800s, Fourth of July in Newport had evolved into a regular festival with a number of planned events, such as the ringing of the bells, artillery and cannon fire in Washington Square and the decoration of local homes and businesses in patriotic colors. The Second Baptist Meetinghouse was the location for the Fourth of July exercises reported by The Newport Mercury in 1809, “After an introductory prayer by the Rev. Mr. Gibson, and the reading of the Declaration of Independence by Nathaniel Hazard Esq., an oration was delivered by Mr. Dutee J. Pearce; the public exercises were intermingled with excellent and appropriate music.” Music was a key part of all Fourth of July celebrations in this time period and services would have included well-known patriotic songs, or newly composed odes by members of the community set to already popular tunes. These exercises followed a regular pattern; many Fourth of July pamphlets published during this time period follow the same structure as this service recorded in The Newport Mercury. (The Newport Mercury, July 8, 1809)

July 4, 1838 – Throughout the early 1800s, The Newport Mercury recorded the celebration of the Fourth of July at the Second Baptist Meetinghouse, but other groups within the town held their own Fourth of July celebrations as well. The Newport Temperance Society held its own Fourth of July service in 1838, separate from the celebration at Second Baptist. The Temperance Movement in America was led by individuals who refrained from consuming alcoholic beverages and wanted others to do the same. The Temperance Society put its own spin on the popular song “America” by changing some of the words to suit its mission, “My country! ‘tis of thee, / ‘tis of thee, / Sweet land of liberty – / Of thee we sing; / Land where our fathers died; / Land of the pilgrim’s pride; / From every mountainside, / Let Temperance ring!” At this time in American history, Fourth of July celebrations included events in which all the inhabitants of a town or city could come together and celebrate, rather than retreating to the privacy of their homes for Fourth of July dinners and toasts. (Broadside, “Order of Exercises for the Temperance Celebration of the Anniversary of American Independence at the Beneficent Congregational Church,” July 4, 1838)

July 4, 1865 – The Fourth of July not only commemorated the American Revolution, but it also provided Americans with the opportunity to reflect on the state of the country during the celebration itself. The Fourth of July celebration at the Second Baptist Meeting House in 1865 took place only a few months after the conclusion of the Civil War and the music played during the service acknowledged that fact, particularly the song “Victory at Last,” which played at the close of the service. This last verse comes from a pamphlet listing the Fourth of July exercises at Second Baptist, “For many years we’ve waited, to hail a day of peace / When our land shall be united, and war and strife shall cease; / And now the day approaches – the drums are beating fast, / And all the boys are coming home, there’s victory at last.” This song not only reflected the mood of the country in 1865, but also paid respect to those who fought in the Revolutionary War almost a century before. (Broadside, “Order of Exercises for the Celebration of American Independence at the Second Baptist Meeting House,” July 4, 1865)

Independence Day celebration in Washington Square, 1884. P9375, Collections of the NHS.

July 5, 1886 – When the Fourth of July fell on a Sunday, celebrations would be postponed until Monday, July 5th and that is exactly what happened in 1886. Fourth of July celebrations by the end of the 1800s were fairly similar to those we experience today and included such entertainments as parades, fireworks displays and sporting events. An advertisement for the Municipal Celebration in 1886, listed a number of public activities for citizens. Some of these activities for the day included a morning parade through downtown Newport and the following events held in Touro Park that afternoon:

- Athletic events with cash prizes open only to Newport citizens.

- Refreshments and music from 2:30-4:30 for the “children of the city.”

- A baseball game in the Parker avenue lot.

- Music in the evening and constant illumination from “colored fires” kept burning in the Old Stone Mill.

In the 1880s, the private dinners and solemn church services gave way to civic entertainment and public festivities that lasted all day and well into the evening. (Broadside, “Municipal Celebration of American Independence in Newport,” July 5, 1886)

July 4, 1899 – The order of activities in a pamphlet advertising the Municipal Fourth of July Celebration in 1899, during the high point in the Gilded Age was very different from the private toasts, early morning bell ringing and military salutes that made up July 4th celebrations a century earlier. In addition to the usual parade and exercises in Touro Park, a hot air balloon was scheduled to sail over Newport with two lucky residents in its basket:

The NHS continues the tradition of ringing the bells of the colony house to mark Independence Day celebrations.

“Professor Rodgers of Boston will make an ascension in his mammoth balloon Volunteer from the lot on Middleton avenue. One of our leading citizens and one of Newport’s fair daughters have signified their intention of accompanying the Professor in his aerialflight among the clouds.” Hot air balloons enabled people to get an aerial view of the city, in a time before the invention of the airplane. This promised a unique and exciting experience, not only for those riding in the balloon, but also for citizens gathered below to watch the flight.

The festivities of 1899 continued into the night, with band concerts and fireworks at Touro Park and City Hall. The Fourth of July had truly become the public holiday we celebrate today, intended to entertain American citizens as we remember the American Revolution. (Broadside, “Municipal Celebration of American Independence in Newport,” July 4, 1899)

July 4, 2020 – With the United States still in the grips of the COVID-19 pandemic, celebrations for the holiday were scaled back; many Newporters will opt to celebrate in small groups at home. The tradition of ringing the bells of the Colony House will continue, as will the long-standing custom of reading the Declaration of Independence – albeit virtually.

Banner: P8680, Photograph depicting a parade float with a figure representing ‘Peace’ moving past the Brick Market, Thames Street.