This is a guest blog post by Maureen Iplenski, MA/PhD in History, American Studies, Certificate in Museum Studies (expected 2026) University of Delaware. Maureen was a 2022 NHS Buchanan Burnham Fellow, contributing towards the “BIPOC Biographies from the Archives of the Newport Historical Society” initiative.

On March 5, 1810, David Smith, an African American sailor, wrote to his Consul in Plymouth, John Howlker, in a panic. Smith was recently impressed by the British Royal Navy. Impressment involved the capture of sailors, who were then forced into service. The possibility of capture was a constant threat for seamen throughout the long-eighteenth century, especially during the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815). The British, in great need of manpower, sought skilled sailors who lived outside their national borders. Americans, who they argued were subjects of the British Empire, were especially susceptible to impressment. Smith was just one out of an estimated 10,000 American sailors who were impressed by the Royal Navy from 1789 to 1815. His letter to Howlker is representative of the many appeals written by captured sailors. Notably, Smith claimed his status as an American citizen. “Sir as I am a Scitisen [citizen] of the united States I Beg your honer would do all you can to free me of this disagreeable Scituwasion [situation].” He also asserted that the British stole his protection certificate, which was the one piece of tangible evidence of his citizenry. In this appeal for freedom, he requested a copy of his certificate.1 This account reveals not only that Smith viewed his protection certificate as a path to liberty, but also that the British – who confiscated it – recognized its authority. In addition to ensuring the safety of American seamen, these certificates defined citizenship and national identity at a time when the newly formed United States struggled to define its nationhood.

Protection certificates asserted citizenship through a set of concrete facts. A sailor’s birthdate, birthplace, and name were written on the certificate, along with their physical description. In 1796, the U.S. Congress ratified the Act for the Protection and Relief of American Seamen intending to defend sailors from impressment. The Act also required sailors to present an affidavit from a witness who could confirm these personal details.2 Sailors could purchase a protection certificate for a small fee of 25 cents from the collector at their local customhouse. By 1812, over 100,000 seamen purchased a certificate.3 The Act established the appropriate language to define American citizenship. Birthplace, most evidently, determined a sailor’s rightful place in this new nation.

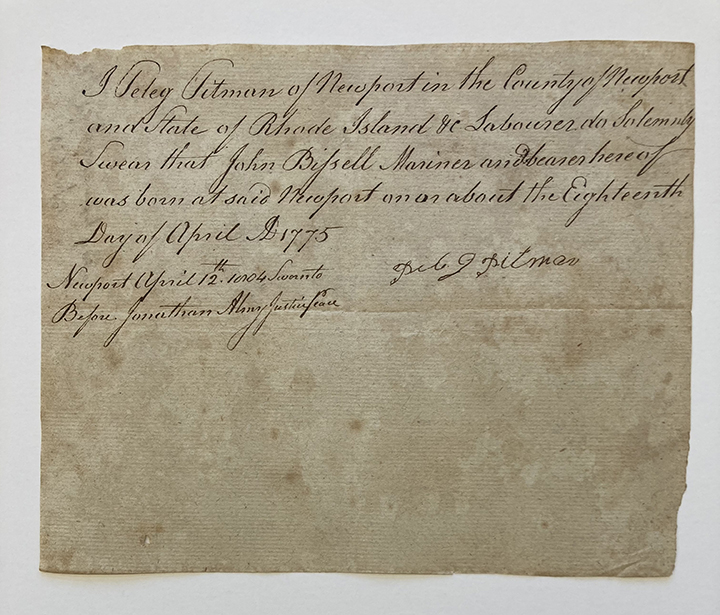

Written Record of John Bissell Seamen Protection Certificate, 1804 (Newport Historical Society Custom House Records, Box 1, Folder 2).

The 1796 Act also required customs collectors to maintain a record of all certificates they approved. In contrast to the certificates distributed to sailors, which were pre-printed and emblazoned with a seal of the United States, these records were hand-written and simplistic. The need for these copies reveal the precarious nature of sea life. The protection certificates, as mentioned in Smith’s letter, were vulnerable to seizure. Constructed from paper, they were also susceptible to everyday accidents, such as spills and rips. Sailors often attached a backing to their certificates in an effort to protect this valued piece of paper.4 The fragility of their citizenship was apparent in such incidents. In his appeal to be relieved of service in the Royal Navy, Elias Linch pleaded for his stained certificate to be accepted by the American consul. “I Dare Say that youre goodness will take That in Consideration & Cleare me From this Serveis.”5 The customhouse records, meanwhile, were well preserved. Sailors frequently requested their customs collector to send them a copy of their certificate. These records provided stable proof of citizenship when such stability lacked at sea.

The purchase of a protection certificate, within itself, was an act of resistance. With this paper in hand, sailors asserted their American identity when that identity was denied by the British. The Royal Navy justified the impressment of American sailors by claiming that these men were British subjects. Americans, who shared the same language and mannerisms as the British, were difficult to discern. Protection certificates drew a necessary line of distinction. Sailors’ assertion of American identity was also a form of resistance against bodily harm. Impressed sailors who refused to fulfill their duties were flogged and forced to run the gauntlet.6 These seamen presented protection certificates to British captains because they believed they had an innate right to avoid such harm as American citizens. Those on shore, meanwhile, championed “sailors’ rights,” which represented one’s freedom to control their own life and labor.7 Impressment unintentionally influenced how Americans understood their rights.8

Black sailors claimed their status as American citizens through protection certificates decades before the United States government granted citizenship to African Americans.9 Their status more or less signaled a demand for labor rather than an egalitarian society at sea. African Americans made up nearly one-fifth of the sailor workforce in Early America.10 Considering that their protection certificate often was the only document identifying them as citizens, Black sailors were more likely to be impressed. Despite the possibility of capture, African Americans recognized a symbolic link between freedom and the sea. As sailors, they could develop skills, learn about news from other parts of the globe, and move freely across the Atlantic.11

Seamen Protection Certificates were valued for their practicality – they were semi-successful at protecting sailors – but they were valued more for their symbolism. They represented a person’s identity as an American citizen, a denial of British subjecthood, and a claim that African Americans were also part of this citizenry. Protection certificates did not free all of those who were impressed. The fate of Smith, and many others, are largely unknown. They, nonetheless, encouraged Americans to imagine an idealistic form of citizenship: one that allowed for a freedom of choice and movement, and one that included all men.

__________________

1 W. Jeffrey Bolster, “Letters by African American Sailors, 1799-1814,” William & Mary Quarterly 64, no. 1 (2007): 174.

2 “An Act for the Relief and Protection of American Seamen.” Legislative Act, 1796. https://www.loc.gov/resource/ rbpe.22301000/?sp=1 3 Paul A. Gilje, “Free Trade and Sailors’ Rights: The Rhetoric of the War of 1812,” Journal of the Early Republic 30, no. 1 (2010): 11.

4 Nathan Perl-Rosenthal, Citizen Sailors: Becoming American in the Age of Revolution (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015), 233.

5 Bolster, “Letters by African American Sailors,” 173.

6 Denver Brunsman, The Evil Necessity: British Naval Impressment in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic World (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2013), 160.

7 Gilje, “Free Trade and Sailor’s Rights”, 9.

8 Denver Brunsman, “Subjects vs. Citizens: Impressment and Identity in the Anglo-American Atlantic,” Journal of the Early Republic 30, no. 4 (2010): 561; Elizabeth Jones-Minsinger, “Our Rights Are Getting More & More Infringed Upon,” Journal of the Early Republic 37, no. 3 (2017): 473. Minsinger characterized early American nationalism among seamen as combative, as they were forced to recognize which rights they valued as a consequence of their imprisonment. Brunsman argued that American sailors personified the distinction between voluntary citizenship and obligatory subjecthood. Impressed Sailors assumed the responsibility of establishing this distinction on an individual-level.

9 The 14th Amendment, which was adopted in 1868, extended citizenship to all those born and naturalized in the United States. The Seamen Protection Certificates Collection at Newport Historical Society includes certificates from three African American sailors: Aaron Buchanan, Prince J. Albert, and Frederick Bailey, each of whom purchased their certificates respectively in 1855, 1850, and 1821.

10 Brunsman, The Evil Necessity, 122.

11 Julius S. Scott, The Common Wind: Afro-American Currents in the Age of the Haitian Revolution (London & New York: Verso Press, 2018), 38.

Primary Sources

“An Extract of the Act Entitled, An Act for the Relief and Protection of American Seamen.” Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/resource/rbpe.22301000/?sp=1

Bolster, W. Jeffrey, “Letters by African American Sailors, 1799-1814,” William & Mary Quarterly 64, no. 1 (2007): 167-182.

Customhouse Records. Newport Historical Society, Newport, RI.

Secondary Sources

Brunsman, Denver. “Subjects vs. Citizens: Impressment and Identity in the Anglo-American Atlantic,” Journal of the Early Republic 30, no. 4 (2010): 557-586

Brunsman, Denver. The Evil Necessity: British Naval Impressment in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic World. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2013. Gilje, Paul A. “Free Trade and Sailors Rights: The Rhetoric of the War of 1812,” Journal of the Early Republic 30, no. 1 (2010): 1-23. Jones-Minsinger, Elizabeth. “Our Rights Are Getting More & More Infringed Upon,” Journal of the Early Republic 37, no. 3 (2017): 471-505. Perl-Rosenthal, Nathan. Citizen Sailors: Becoming American in the Age of Revolution. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015. Scott, Julius S. The Common Wind: Afro-American Currents in the Age of the Haitian Revolution. London & New York: Verso Press, 2018.