This is a guest blog post by Sam Dinnie (they/them), a PhD student in early American history at The George Washington University. Sam is a 2023 Buchanan Burnham Fellow.

Portrait of Ezra Stiles painted by American artist Nathaniel Smibert, 1756. Courtesy of the Yale University Art Gallery.

Ezra Stiles was born in North Haven, Connecticut, in 1727 to Reverend Isaac Stiles and Kezia Taylor Stiles. Stiles graduated from Yale in 1746 and was ordained as a minister three years later. His ensuing life achievements make it easy to celebrate him as the “most learned man in New England.” Stiles helped to found Brown University, exchanged ideas with fellow scientists such as Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin, and joined numerous societies for the promotion of the arts and sciences in the new United States. While these accomplishments are undoubtedly significant, the portrayal of Stiles as an estimable member of the learned New England elite is not a holistic one. Like his contemporaries, Stiles profited from forced labor, promoted Manifest Destiny, and conceived of servitude, slavery, and freedom as race-based.

Stiles moved to Newport in 1755 and took up the pulpit at the town’s Second Congregational Church on Clarke Street. The congregation then voted to fund the construction of a house for Stiles across the street from the meetinghouse. The project began in 1756 and, like many buildings in Newport, was completed in 1757 by free and forced laborers. In late 1756, John Stevens submitted a receipt of costs incurred to the committee appointed to oversee the venture for reimbursement. Stevens frequently documented payment owed to him for lending out “my Man” and “my Boy,” references to enslaved people he owned.[1]

Stiles himself purchased enslaved people, both for his own household and for his father, Isaac. That Stiles bought enslaved people shortly after he moved to Newport is no coincidence. Based on data from the 1774 Rhode Island census, Elaine Foreman Crane calculated that of the 1,538 white families in Newport, 460 owned at least one enslaved person.[2] 410 of those 460 white families owned one to four enslaved people, demonstrating the ubiquity of domestic slavery in eighteenth-century Newport.[3] Of non-white families represented in the 1774 census, Crane totals fifty-two Black families, which indicates that 162 free Black people were counted in the census.[4] Taken at face value, those 162 individuals represented 13% of the Black population in Newport.[5] By extension, 87% of Black people were enslaved or forced laborers. Although perhaps excluding some free Black people or Black indentured servants living in white households, Crane’s statistic nonetheless communicates the extent of domestic slavery in Ezra Stiles’s Newport.

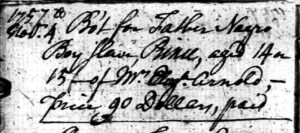

Record of Stiles’ purchase of Prince, noted in his diary on November 4, 1757. Microfilm (185:28) courtesy of the Redwood Library and Athenaeum.

The enslaved person Stiles bought for his father, Isaac, did not stay in Newport. Isaac Stiles was then living in North Haven, Connecticut, so Prince (the enslaved individual Ezra purchased) was transported over one hundred miles west to, most likely, be a domestic slave in Isaac’s household, considering Isaac’s affluence as the town’s minister and advanced age. On November 4, 1757, Stiles documented that he “Bo’t for Father Negro Boy Slave, Prince, aged 14 or 15 of Mr Eleazr Arnold, — price 90 Dollars, paid.”[6] In a November 22, 1757, memorandum of money Isaac owed his son, Ezra recorded: “1 Doll. for Tea, & 95 Dollars for Negro Boy.”[7] He charged his father an extra five dollars for the enslaved boy—possibly as interest—so he could profit from the sale.

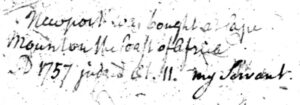

In 1756, Stiles invested in a voyage bound for the west coast of Africa to purchase captives to be sold into enslavement in the Americas. In an “Amots Disbursts of Year ending Octr 22 1756,” Stiles noted to “Add for Negro &c — 100” to the total sum of charges.”[8] That same year, the Snow Venus, owned by William Vernon and Robert Stevens and captained by William Pinnegar, left Rhode Island for Cape Mount in West Africa.[9] After spending months docked on the African coast to acquire captives, the Venus crossed the Middle Passage with 121 Africans on board and reached Kingston, Jamaica, by late March 1757, the principal place the captives were sold.[10] In June 1757, Stiles documented that he “Insured 50 Dollars on Negro on Board Capt Pinniger at Jamaica,” which, in all likelihood, is in reference to the Venus.[11] Stiles purchased this insurance to protect his initial investment in Vernon and Stevens’s business venture in the capture and sale of human beings. The Venus returned to Rhode Island in the latter half of 1757 with captives for the voyage’s investors, Ezra Stiles included. Stiles recorded that he received an eleven year old boy who he named Newport: “Newport was bought at Cape Mount on the Coast of Africa. . . judged at 11. my Servant.”[12]

“Newport was bought at Cape Mount on the Coast of Africa. . . judged at 11. my Servant.” Microfilm (1:76) courtesy of the Redwood Library and Athenaeum.

The captain’s name, itinerary, and timeline of the Venus coincide with Stiles’s business accounts, almost certainly indicating that this was the ship Newport was taken on. Newport would have been one of the 121 captives on board, 114 of whom survived, making the voyage mortality rate 6%.[13] After experiencing the unimaginable horrors of the Middle Passage, Newport endured twenty-one years of enslavement in Stiles’s household. It is unclear what Newport’s experience was while enslaved in the Stiles house. The known extant documents that we have to reconstruct Newport’s story are records of the Snow Venus and Stiles’s personal writings and business accounts. Newport only infrequently appears in Stiles’s diary. What we can learn from those sparse entries is that Newport attended meeting with the Stiles family, was inoculated for smallpox in May 1778, and was baptized by Stiles on March 12, 1775: “baptized my Negro Man Newport (aet. 27, nearly) and admitted him into full Communion with the Church.”[14] Hopefully there is yet to be discovered documentation that amplifies Newport’s voice and conveys his experience as he lived it, not as his enslaver saw it.

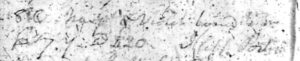

Stiles emancipated Newport on June 9, 1778, as part of managing his estate in preparation for his move to New Haven, Connecticut, to become the seventh president of Yale College. Under the heading “Removal to Connecticutt,” Stiles documented that he “liberated my Negro Servt Newport aet. 30.”[15] In his diary, Stiles again wrote that he “freed or liberated my Negro Man Newport, about aet. 30” the same day he departed with his children for New Haven.[16] We do not know if he provided Newport monetary support, employment, or housing, nor do we know what exactly Newport’s circumstances were when Stiles returned to Aquidneck Island for a visit in October 1781. On October 2, Stiles reported in his diary that he was “Visitg Portsm[outh] Friends all week,” and October 7, he “preached all day to my former Congrega.”[17] While reuniting with friends, colleagues, and congregants, Stiles also saw Newport, his wife, Violet, and their infant son, Jacob. How and why the meeting took place is unclear, but Stiles detailed the result in his diary, dated October 8: “Newport & Violet bound to me for 7 years @ £20. Left Portsmo.”[18]

Indenture of Newport and Violet by Stiles. Microfilm (2:272) courtesy of the Redwood Library and Athenaeum.

That Stiles used the word “bound” and set a seven-year term with a fixed salary suggests that he contracted Newport and Violet as indentured servants. Stiles did not specify how this arrangement was reached or what the terms were, but by indenturing Newport and Violet rather than paying them wages, Stiles wielded added control over their labor. The indenture most likely mandated that Newport and Violet serve Stiles in New Haven, which required them to leave Rhode Island. On December 23, 1782, Stiles reported that “Came my former Manservant Newport” to New Haven “who with his Wife & Child left Rh. Isld 15th Inst. I have hired them for seven Years at £20 per Annum.”[19] A diary entry five days later reveals that Stiles also indentured the couple’s son, Jacob, separate from his parents’ contract: “The Child Jacob two years old last Month and bound to me till aet. 24.”[20] The editor of Stiles’s diary states that Violet “left Dr. Stiles’s service on July 1, 1784, the child (Jacob) remaining,” which was about six months after Stiles documented that her and Newport’s second son, Abraham, was born.[21] Seeing as the transcribed diary was published in 1901, there is unsurprisingly no source cited to verify the date of Violet earning her freedom.

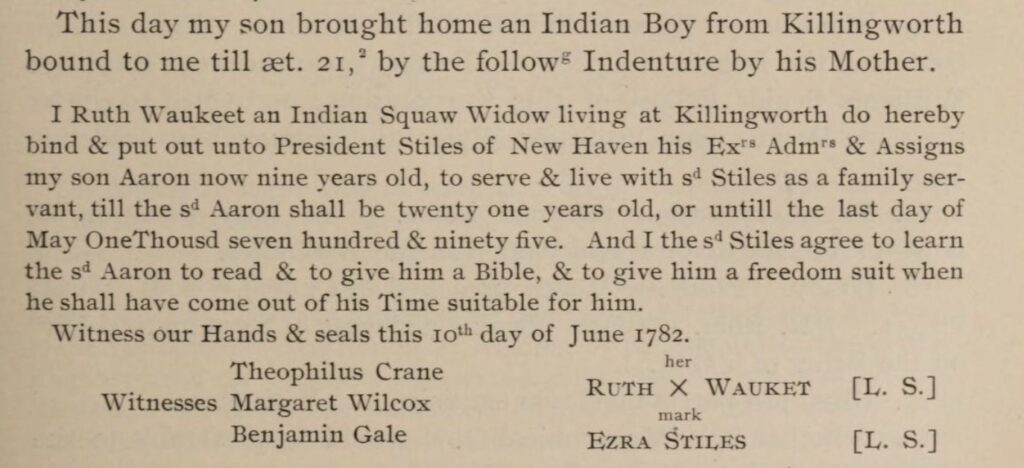

The two-year-old Jacob joined another indentured child in Stiles’s household named Aaron. In a diary entry dated June 11, 1782, Stiles logged that his “son brought home an Indian Boy from Killingworth bound to me till aet. 21, by the followg Indenture by his Mother,” Ruth Waukeet, who Stiles identified as “an Indian Squaw Widow.”[22] Stiles does not detail why his son took Aaron from Killingworth, a town in Connecticut about twenty-five miles east of New Haven, or the circumstances that resulted in the indenture. Stiles’s silence prompts us to consider questions such as: What was the nature of the relationship between the Stiles men and Ruth and her son? What could have led Stiles’s son to seek out this specific child? What could have driven Ruth to resort to an action as desperate as indenturing her child? How much, if any, say did Ruth have in creating the indenture contract? We can only speculate answers to these queries. One clue that we do have in interpreting what exactly transpired is that Stiles copied her signature as “Ruth X Wauket her mark,” indicating that she was probably unable to read the terms of the indenture that stipulated Aaron was bound to Stiles “till the sd Aaron shall be twenty one years old, or untill the last day of May OneThousd seven hundred & ninety five.”[23] We do not definitively know what became of Aaron after the indenture was signed, but a note from the editor of Stiles’s diary suggests that Aaron was returned to his mother in May 1783.[24] The accuracy of this note, however, is suspect, given that the diary was published in 1901 and the editor references no documentation to support the claim.

Transcription of the indenture of Aaron, a nine-year-old Indigenous boy. The Literary Diary of Ezra Stiles (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1901), 3: 21.

Stiles’s indenturing young children of color was not only about exploiting their labor; it was about power. Stiles was a Protestant evangelist determined to Christianize non-Euro-Americans. A term of Aaron’s indenture was that Stiles “learn the sd Aaron to read & to give him a Bible.”[25] In 1776, Stiles and Samuel Hopkins, minister of Newport’s First Congregational Church, published To the Public. The pamphlet outlined their plan to send trained native-born African missionaries to Africa and implored the public to make donations to fund the operation. As historian Paul Polgar argues, a major motivation for the mission was to “realize the millennialist dream of Christianizing all of earth.”[26] Stiles had taken that dream to extremes in his personal writings in the 1760s when he fantasized about fathering a large New England family connected by his blood and bound by laws he set to fashion himself an eighteenth-century patriarch Abraham.[27] Around the same time, Stiles promoted the idea of Manifest Destiny. He asserted that within a few generations, the Native American population would diminish completely, making the entire North American continent open to Euro-American expansion.[28]

Stiles further articulated a vision of Manifest Destiny in a sermon he delivered before the Connecticut General Assembly in 1783—the year the Revolutionary War ended—in which he also declared his belief that slavery, servitude, and freedom are race-based. Stiles proclaimed that “we,” meaning the white population, “are increasing with great rapidity; and the Indians, as well as the million Africans in America, are decreasing as rapidly. Both left to themselves, in this way diminishing, may gradually vanish: and thus an unrighteous SLAVERY may at length, in God’s good providence, be abolished and cease in the land of LIBERTY.”[29] In other words, slavery would disappear because the people being enslaved would. Stiles maintained that his prediction was part of the providential plan for the United States to become the world’s first successful democratic republic and to populate the continent with white Christians.[30]

Plaque in Ezra Stiles College, Yale, that honors three men whose lives were controlled Stiles. Courtesy of the Yale Daily News.

In 1798, three years after Stiles’s death, Abiel Holmes, a Congregationalist minister, budding historian, and husband to Stiles’s daughter Mary, published The Life of Ezra Stiles. Holmes’s biography painted a glowing portrait of the late Stiles, writing that Stiles, “possessing a soul glowing with philanthropy, he exerted his own ability, and used his influence with others, to lessen the sum of human misery.”[31] The attestation of Stiles’s benevolence conceals his Euro-Christian supremacist views, connection to slavery and servitude, and the existence of Newport, Violet, Jacob, Aaron, and Prince. This side of Stiles has recently come to light. In 2016, Yale University installed a plaque in the residential Ezra Stiles College that acknowledges Stiles’s involvement in slavery and indentured servitude and honors the memories of Newport, Jacob, and Aaron. The text concludes with a statement that ought to guide how we approach studying Stiles and others whose affluence stemmed from the forced labor of named and unnamed individuals: “We remember them here.”[32]

[1] John Stevens account to the Ministry Committee, 1756, Second Congregational Church Receipts, Bills, Memorandum, 1757–1772, Second Congregational Church Records, 1715–1833, Newport Historical Society.

[2] Elaine Foreman Crane, A Dependent People: Newport, Rhode Island, in the Revolutionary Era (New York: Fordham University Press, 1985), 58.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid., 82.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Miscellaneous Volumes and Papers, 185:28, Ezra Stiles Papers [microfilm], Redwood Library and Athenaeum.

[7] Miscellaneous Volumes and Papers, 185:29, Ezra Stiles Papers [microfilm], Redwood Library.

[8] Miscellaneous Volumes and Papers, 175:13, Ezra Stiles Papers [microfilm], Redwood Library.

[9] Voyages: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/database, Voyage ID 36207, accessed August 1, 2023.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Miscellaneous Volumes and Papers, 185:22, Ezra Stiles Papers [microfilm], Redwood Library.

[12] Itineraries, 1:76, Ezra Stiles Papers [microfilm], Redwood Library.

[13] Voyages, https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/database, Voyage ID 36207, accessed August 1, 2023.

[14] Franklin Bowditch Dexter, ed., The Literary Diary of Ezra Stiles (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1901), 1: 525 (quote); Franklin Bowditch Dexter, ed., The Literary Diary of Ezra Stiles (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1901), 2: 269.

[15] Itineraries, 5:137, Ezra Stiles Papers [microfilm], Redwood Library.

[16] The Literary Diary of Ezra Stiles, 2: 272.

[17] Ibid., 558.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Franklin Bowditch Dexter, ed., The Literary Diary of Ezra Stiles (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1901), 3: 50.

[20] Ibid., 51.

[21] Ibid., 50n1.

[22] Ibid., 25.

[23] Ibid. In the transcript of the indenture, Stiles alternates between two spellings of Ruth’s surname: Ruth Waukeet and Ruth Wauket.

[24] Ibid., 25n2.

[25] Ibid., 25.

[26] Paul J. Polgar, Standard-Bearers of Equality: America’s First Abolition Movement (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2019), 226.

[27] Christopher Grasso, A Speaking Aristocracy: Transforming Public Discourse in Eighteenth-Century Connecticut (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1999), 256.

[28] Grasso, A Speaking Aristocracy, 255.

[29] Ezra Stiles, The United States elevated to Glory and Honor. . . (New Haven, CT: Thomas & Samuel Green, 1783), 14.

[30] Ibid., 15.

[31] Abiel Holmes, The Life of Ezra Stiles (Boston: Thomas & Andrews, 1798), 372–73.

[32] David Yaffe-Bellany, “Plaque honors three men controlled by Ezra Stiles,” Yale Daily News, August 18, 2016, https://yaledailynews.com/blog/2016/08/18/plaque-honors-three-men-controlled-by-ezra-stiles/.