Zoe Hume, MS graduate, Florida State University, is one of the 2021 Buchanan Burnham Fellows working on capturing data from the NHS archives on Black and Indigenous people of color in colonial Newport, Rhode Island. The following post relates to Cudjo Vernon, an enslaved individual in the Vernon household.

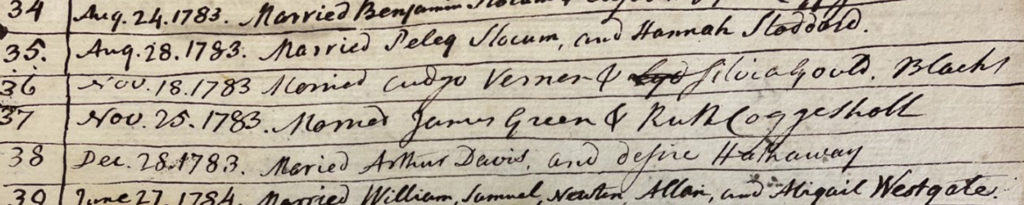

In my previous post, I wrote about the importance of names and explored the idea that the names of enslaved people recorded in historical archives might not be the names they would have chosen to be remembered by. I cited Cudjo Vernon as an example of this. In the document I explored, dated November 11th, 1782, Cudjo wrote to Samuel Vernon (Samuel Vernon III, 1744-1809) asking for permission to marry a woman named Sylvia. The following year, their marriage was recorded in the First Congregational Church of Newport’s marriage and baptism records (NHS Vol.832), November 18th, 1783.

Marriage of “Cudgo” Vernon and Sylvia Gould, recorded in the First Congregational Church records of marriages and baptisms (1744-1825). NHS Vol.832, NHS Collection.

Based on these two documents, one might infer an uncomplicated marriage union between this couple. The story is not nearly that straightforward.

I recently examined two letters in the NHS archives from Samuel Vernon to his father, also Samuel Vernon (Samuel Vernon II, 1711-1792) that shed more light on Cudjo Vernon, and his connections to other enslaved individuals owned by the Vernon family, including a woman named Belinda.

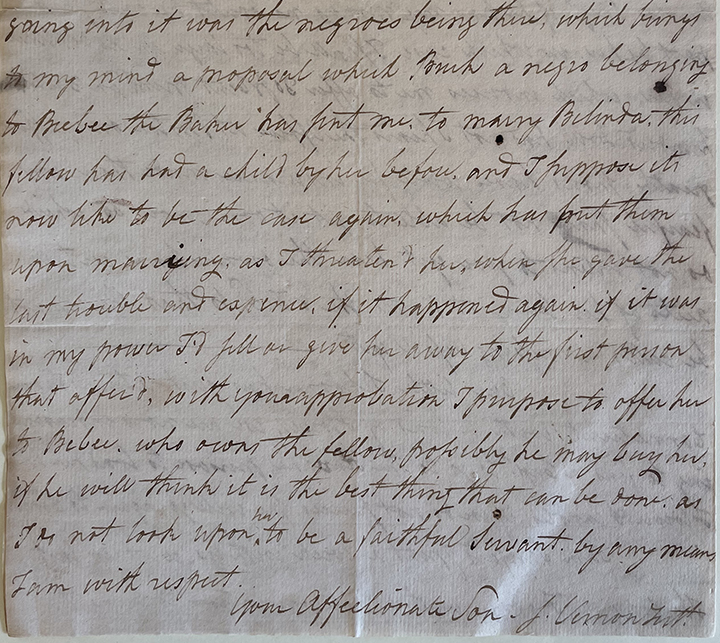

In a letter dated April 15th, 1782, Samuel tells his father that Bush, an enslaved man belonging to Nathan Bebee, a baker, has asked for permission to marry Belinda, an enslaved woman in Samuel’s household, with whom Bush has previously had a child. Samuel suspects Belinda is with child again. He writes, “I suppose it now like to be the case again which has put them upon marrying, as I threatened her when she gave the last trouble and expressed if it happened again, if it was in my power, I’d full on give her away to the first person that offered.” Samuel suggests to his father that the matter could be resolved if Bebee buys Belinda.

Letter from Samuel Vernon to his father, relaying Bush’s request to marry Belinda. Box 43A, Folder 26, NHS Collections.

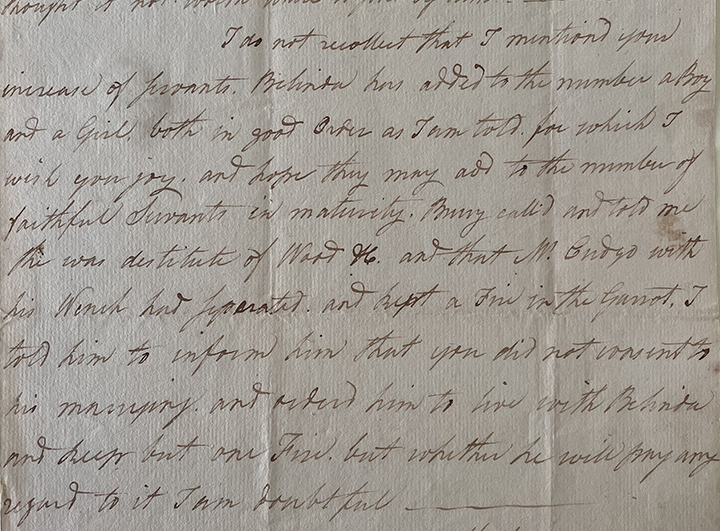

In a second letter dated January 27th, 1783, Samuel tells his father that the enslaved woman Belinda has birthed two children, a boy and a girl. He goes on to share information received from Burry Vernon, another enslaved individual, that “Mr. Cudgo [sic] with his wench had separated and kept a fire in the garrot1 [sic], I told him…that you did not consent to his marrying, and ordered him to live with Belinda and keep but one fire. But whether he will pay any mind to it I am doubtful.”

Letter from Samuel Vernon to his father, announcing the birth of Belinda’s children, and his intentions for Belinda and “Cudgo” to live together. Box 43A, Folder 26, NHS Collections.

Is the “wench” in question Cudjo’s future wife Sylvia, or could there have been another woman? Cudjo’s November 11, 1782, letter asking permission to marry Sylvia suggests he would not have been happy if the Vernons forced him to marry Belinda. The fact that Cudjo married Sylvia tells us he either did so without the Vernons’ permission or eventually gained their consent. Perhaps we will unearth more letters to help fill in this gap in Cudjo’s story, and find out what happened to Belinda, but for now all we know is that somehow Cudjo Vernon made his own choice within a system designed to prevent that very thing.

Working in the archives can make you feel like a detective, and your case may be hundreds of years old. Anyone who has tried to build their family tree knows how it feels to try to match names, dates, and places to track their ancestors through history. When working with common names, it can be even harder to determine if a set of records are for the same person or entirely different people who existed in the same place at the same time.

Unfortunately, when it comes to piecing together the lives of enslaved people, there is often very little to work with; and even when you feel you have put together a somewhat decent narrative, the discovery of one document can not only add to the picture, but can also completely change how we look at the pieces we already had. The discovery of these two letters adds drama and depth to what might have once seemed like a straightforward marriage event between two people. It reminds us that behind every name and date on these records we use to piece together our histories are actual people with dynamic stories waiting to be discovered.

1 This could be a misspelling of “garret,” which is a room immediately beneath a roof and is often used interchangeably with “attic.” In New England, enslaved people often slept in garrets or basements. When Samuel says Cudjo should “keep but one fire,” he likely means maintain one household.