Zoe Hume, MS graduate, Florida State University, is one of the 2021 Buchanan Burnham Fellows working on capturing data from the NHS archives on Black and Indigenous people of color in colonial Newport, Rhode Island. The following post relates the marriage of enslaved people.

As a Buchanan Burnham Fellow at the Newport Historical Society, writing about the Vernons has become an ongoing series for me. Both my first and second blog posts featured Cudjo Vernon, a freed man once enslaved to Newport’s well known Vernon family. Both posts mentioned his marriage to Sylvia Gould, though the second challenged the idea of their marriage as a straightforward event. In that post, I cited archival documents in which Samuel Vernon, a member of the family Cudjo was enslaved to, contested Cudjo’s marriage to Sylvia and attempted to have him marry another enslaved woman named Belinda instead. Yet, according to the First Congregational Church of Newport’s marriage and baptism records (NHS Vol.832), Sylvia and Cudjo married on November 18th, 1783, which means Cudjo either married without consent or somehow convinced the Vernons to give their permission.

Enslaved people could not legally marry since the law viewed them as chattel, and even if two enslaved people did “marry,” their union was ultimately subject to the whims of their enslavers. Enslaved families might be spread across different households, and while Rhode Island enacted a “gradual emancipation” law in 1784 that stipulated children born to enslaved mothers would be emancipated at a certain age (originally 18 for women and 21 for males but later 21 for all)1, any children an enslaved woman had were considered the property of her enslaver.2 As a result, some enslavers saw benefits to marriages or sexual relationships among enslaved people, while others saw children as a burden. Samuel Vernon represented both stances; based on a letter to his father from April 15th, 1782, Samuel Vernon was initially furious over Belinda’s pregnancy. By January 27th, 1783 , he had changed his tune, when he wrote of Belinda’s delivery of two children, a boy and a girl, and added, “I wish you joy, and hope they may add to the number of faithful servants in maturity.”

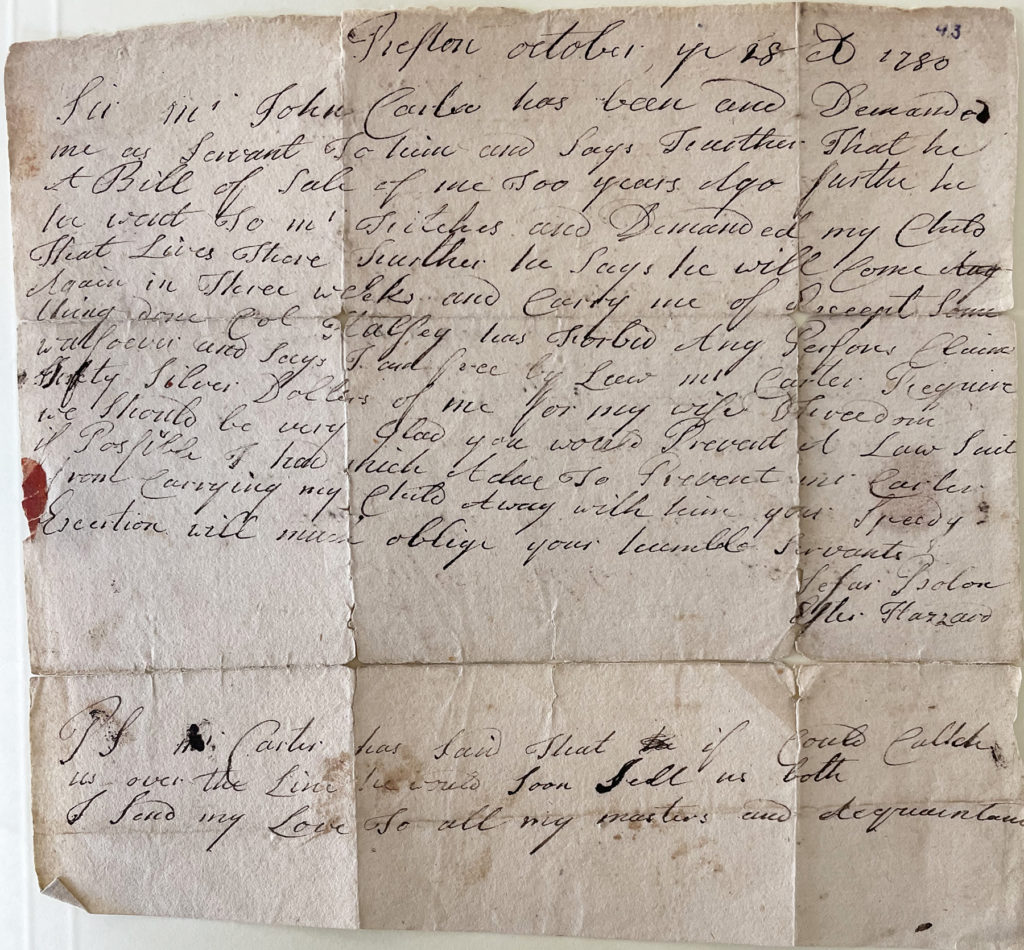

While enslavers may have allowed enslaved couples to be in relationships, the enslaver could force people into unions they had no interest in, which we saw in Samuel Vernon’s attempt with Cudjo and Belinda, or they could easily separate a family through sales, loans, or hiring out of enslaved people. Even freed families faced the threat of sudden separation. In a letter from Sesar Bolon and Esther Hazard of Preston, Connecticut, to Thomas Hazard of South Kingstown, Rhode Island, dated October 28th, 1780, Sesar describes threats made by a John Carter to enslave Sesar, Esther, and their child who lives with “Mr. Fitches.” Sesar writes that one “Colonel Halsey” has assured Sesar of his own freed status, but Sesar and Esther ask for Thomas Hazard’s intervention on Esther’s behalf. Based on a letter held by the Rhode Island Historical Society (Mss 9001-H Box 4), we know that Thomas Hazard’s sons, George and Benjamin Hazard, wrote back on January 3rd, 1781, reaffirming Esther’s freed status in the will of their mother Susannah Hazard (South Kingstown Town Council and Probate Records, Volume 5 1754-1772 p. 316, 317, 330. Town Hall, Peacedale.)

A letter from Sesar Bolon and Esther Hazard of Preston, Connecticut, to Thomas Hazard of South Kingstown, Rhode Island, dated October 28th, 1780, in which Sesar describes threats made by a John Carter to enslave Sesar, Esther, and their child. Box 43A, Folder 26. NHS Collection.

Many books and articles about marriages among enslaved people in the antebellum period, particularly in the South, often use the phrase “‘till death or distance do you part,” which is more pithy than what they may have really said in enslaved marriage ceremonies. For example, Reverend Samuel Phillips, whose pastorate in Andover, Massachusetts, extended from 1710 to 1771, used “Form of a Negro Marriage” when called to preside over Black unions, and the vows included the reminder that, “both of you…Remain Still as really and truly as ever, your Master’s Property, and therefore, it will be justly expected, both by God and Man, that you behave and conduct your-selves, as Obedient and faithful Servants towards your respective Masters & Mistresess for the Time being.”3 Both quotes, historic and otherwise, serve as powerful reminders that enslavement encompassed all aspects of a person’s life.

Perhaps Samuel Vernon eventually gave Cudjo permission to marry Sylvia, perhaps one of the elder Vernons stepped in and consented, or perhaps they married without permission. Though we may not know how they came together in a time where their right to do so was not legally recognized, the evidence shows that Cudjo Vernon and Sylvia Gould’s did, against all odds, making their story a remarkable example of agency and power among Rhode Island’s Black population.

[1] An Act for the gradual abolition of slavery, 1784. Rhode Island State Archives.

[2] Wilentz, S. (2019). No property in man: Slavery and antislavery at the nation’s founding, with a new preface. Harvard University Press.

[3] As quoted in Howard, G. E. (1904). A history of matrimonial institutions. University of Chicago Press. https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/49247